The Resistance

A hub of creativity for early airplane builders: North Carolina? Ohio? Nope—Oregon. And these Oregonians had an independent streak.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/outlaws_388-may07.jpg)

In 1912, Silas Christofferson brought Portland, Oregon, into the age of the airplane. The 24-year-old took off in a Curtiss pusher from the roof of the 12-story Multnomah Hotel, flew for 12 minutes, then set down in Fort Vancouver, on the Washington side of the Columbia River. Thousands of people crowded the streets to see their first airplane flight, and for a few of them, the moment fixed their path through life.

Throughout the early 1900s, small communities of young airplane enthusiasts coalesced around nuclei of designers and personalities scattered across the state. One little group operated, tenuously, from the Rose City racetrack on the eastern edge of Portland. Twenty miles west, near the tiny town of Cornelius, a cadre gathered around designer Les Long, who would later be called the father of homebuilding. Other groups formed about a hundred miles south, in Eugene and Springfield. There was even a gathering in remote Klamath Falls, east of the Cascade Mountains.

But the real heart of grassroots aviation in Oregon began to beat just west of Portland, in the hayfields of Beaverton.

One young Beaverton resident, having heard about Christofferson’s plans, walked five miles from his home to catch a streetcar into Portland, where he joined the crowds craning their necks to get a glimpse of the racketing biplane. Charlie Bernard had been hooked on the idea of flying for quite a while. The streetcar he rode to high school ran past the Adcox School of Aviation, where students were building a very simple glider, launched by an elasticized cord. Bernard, fascinated, often skipped school and spent the day there instead, talking and working with the students. “My heart and soul was in Adcox, not my school,” he said in an interview with oral historian John Patton in 1978.

Without his father’s permission, he invited the students to the family farm in Beaverton, where they assembled the glider in the barn. Occasionally, Bernard and his saddle horse would substitute for the launch cord, galloping down the sloping pasture and dragging the glider into the air with a rope cinched around the saddle horn. Flights were measured in seconds. If the wind was right, the glider would gain enough altitude to permit a turn and landing. “Sometimes they’d fly a hundred feet, sometimes they’d fly a thousand feet,” Bernard said. “It depended on the pilot and the conditions. At any rate, the boys were in the air.”

Soon enough Bernard’s father became aware of what he considered immature antics in the family hayfield and put a stop to it, insisting that Charlie finish school and prepare himself for a real career. Charlie reluctantly complied, and in 1916 the field closed and the glider disappeared. For the next 12 years he kept his fascination with flying to himself, indulging his mechanical interests by selling cars. When his father died in 1928, he obtained some property from an uncle, not far from the original glider field, and started clearing brush. He had a plan.

Bernard’s venture into the car business had acquainted him with the local mechanics, and he was drawn to a garage run by a man named Elmer Stipe. Working for Stipe was George Yates, who would become one of the more talented and innovative aircraft designers and builders in the country. Stipe had become interested in flying, and asked Yates to build an airplane that the two of them could use. Bernard offered them the use of his field—“I was interested in the airplane, I was interested in George Yates, and I was interested in Mr. Stipe, so I built them a hangar.” Within weeks, other pilots and aircraft builders began showing up, so Bernard built more hangars along both sides of the field.

Occasionally, the right people come together at the right time and in the right place, and the intersection changes history. In Beaverton, Oregon, in the early decades of the 20th century, the right people banded together to form a new flying movement: a community devoted to homebuilding. It’s a structure that survives today, in local clubs where members help one another build and fly aircraft.

By then, the state government had taken notice of all the aircraft design and flying going on throughout the state. “Bill Would Curb Fliers” a page 6 headline had proclaimed in the January 20, 1921 Portland Oregonian newspaper. An article the following July noted that “the airplane, in common with the automobile, motorcycle and other vehicles, has been subjected to state regulation under a new law.” The governor appointed a pilot examination board, and the state began requiring aircraft to be examined and registered. For $10, the applicant would receive “a number plate, which must be attached and displayed...on the aircraft.” It was a fairly relaxed form of regulation, and did not appear to discourage aerial experimentation in Oregon. State license plates began appearing on airplanes of all descriptions.

In Beaverton, the airplane Yates built for Stipe was a two-seat tandem design with a parasol wing. Known as the Stiper, it eventually flew some 4,000 hours, carrying hundreds of passengers and students. Other homebuilt designs began emerging from the hangars. Pilot Johnny Bigelow, one of the Beaverton crowd, recalled in another John Patton interview that “experimenting was absolutely uninhibited and unrestricted. You could have a state inspector come out and license your airplane for a few dollars. This created a climate that was pretty hard to beat, anywhere in the world.”

Photographs of Bernard’s field during the 1930s bear him out, showing airplanes of all kinds scattered across the 60 acres, the majority of them homebuilt. There were high-wing airplanes, low-wing airplanes, and even one airplane with no wings at all—a design by Marvin Joy with a halibut-shaped lifting surface and two tiny Salmson radial engines mounted just above the landing gear. (Pilot-mechanic Danny Grecco said he made two brief hops in it and noted, unsurprisingly, that the craft had no lateral stability.) Bigelow himself flew a Heath Parasol, built from plans sold by Ed Heath, who would later become famous for his Heathkits—kits for assembling your own stereos and other electronics. Even though the Henderson motorcycle engine in the nose was supremely unreliable, Bigelow flew the Parasol constantly, excited to be part of the Beaverton gang and the age.

It didn’t hurt the cozy world of state-regulated aviation that the state aircraft inspector was an enthusiastic pilot and supporter of amateur-built airplanes. In 1934 Allan Greenwood was appointed to the Oregon State Aeronautics Board, where he was charged with inspecting and licensing airplanes built within the state. Greenwood issued most of the licenses to airplanes built by experimenters and amateurs, some of which had achieved national recognition. Les Long, who had a small airfield on his farm, had published plans for his Longster in Popular Mechanics, and, by writing for several aviation publications, had become a prominent voice for “the little fellow.” George Yates had established a shop at Bernard’s airport, where he produced several airplanes, including a twin-engine design called the BiMotor, all based on his unique basket-weave construction—an immensely strong material made of geodetic woven strips of wood. Another fixture at Bernard’s was Walter Rupert, who set national altitude records with his Rupert Special, a parasol monoplane with a Salmson radial engine.

While the government of Oregon had established a climate of tolerance for experimental airplanes, across the rest of the country, the federal government was doing the opposite. The Bureau of Air Commerce, created in 1926, became the first federal agency to take responsibility for certifying civilian aircraft. The bureau wrote provisions for licensing general-purpose aircraft. But the closest thing it had to a classification for one-of-a-kind designs was an experimental category, NX, granting manufacturers a 30-day period to test new models. As for homebuilt aircraft, they could not be registered. In 1938, the bureau became the Civil Aeronautics Authority (ancestor of the present Federal Aviation Administration) and began to inspect, regulate, and register airplanes with new energy.

In Oregon, the flying communities met CAA inspectors with everything from polite indifference to outright aggression. When a federal inspector showed up at the Hillsboro airport incognito, flight service operator Ed Ball knew immediately whom he was dealing with. Ball and his designing partner, Swede Ralston, had registered their airplanes with the CAA, but Ralston had friends who were still operating with only state licenses and registrations. A chuckling Charlie Bernard told John Patton what happened next: “Ed called and told me he was sure this fellow was headed for Beaverton to catch unlicensed pilots. When he showed up, I acted like I didn’t know who he was. He wanted to buy a ride, he said, and when I showed him one of the [federally legal] airplanes he said no, he didn’t want to ride in that, he wanted to ride in that pretty yellow one. Then he wanted to take pictures. I pointed him out to George Yates. George was a powerful man, and he put one hand on this fellow’s collar and the other on his belt, took him off the field, and told him he could take all the pictures he wanted from the public road, but he couldn’t come back on to the airport.”

One of the techniques the Department of Commerce used to force pilots into the federal fold—one that really irritated Beaverton’s state-licensed pilots—was to establish “commercial air lanes” between most of the larger airports. An air lane comprised 10 miles on either side of a line connecting two airports; any aircraft within it was subject to federal regulation. The 20-mile width of the lanes made it virtually impossible for a pilot to use the majority of airports without flying through federal airspace.

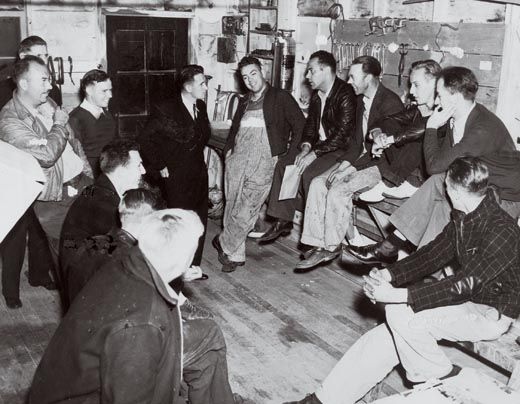

To the pilots of Bernard’s field, this was a sky-grab, pure and simple. The airmen, who would become known as the Beaverton Outlaws, felt that as long as they stayed within Oregon, they did not need regulating by the federal government, so they flew as much as they could while avoiding anybody that looked like a federal inspector. George Yates did his part. Yates was almost always at his hangar on the north end of Bernard’s and normally kept the doors open year-round. If a federal inspector appeared, Yates would quietly close the hangar doors, and any approaching pilot with an unregistered aircraft would get the message and go someplace else to land.

The Outlaws also faced threats from within their own state. In October 1939, Republican governor Charles Sprague fired Greenwood for the sin of serving as president of the state’s Young Democrats. When the state aeronautics board adopted a resolution praising Greenwood’s service and granting him another month’s salary, the governor sacked the board members too. “The attitude…of the Board shows a lack of cooperation I will not tolerate,” Sprague snarled in a press release. “I shall ask the reorganized Board to make a fresh study to determine how much need there is for a State Inspector or Director of Aeronautics.”

One of those appointed to the new board was Salem businessman and aviator Lee Eyerly. Eyerly was starting a company to produce a small airplane based on a Les Long design, so he was vitally interested in the question of how aircraft were to be licensed within the state. Early in his tenure he met with federal officials. In February 1940, he sent a letter to Sprague, describing a meeting with a Mr. Walker and E.B. Cole, CAA authorities from Washington, D.C. “[They] accompanied us to the Beaverton airport,” wrote Eyerly. “[T]hey let it be known that it was their wish that we fall in line with their regulations; but after showing them our side of the picture, Mr. Cole seemed somewhat perplexed…an alternative suggested by both Mr. Cole and the Board was for the CAA to cite some individual for a violation and make a test case of it to determine whether the CAA or the State holds jurisdiction over intra-state flying.”

A month later, Harold Wagner and Donald Wray, both licensed by the state of Oregon, became Eyerly’s case. They took off from Bernard’s, which was one end of the shortest airmail route in the country—the 15-mile Portland-to-Beaverton trip—and thus part of an air lane. Both were promptly issued citations and fined $100.

Late in 1940 the case went to court. But before it could be resolved, Pearl Harbor was attacked.

After the United States entered World War II, the federal government decided that small aircraft flying in U.S. airspace without radios posed a threat, since they could not always be readily identified as friend or foe. Civilian aircraft were tucked away in hangars, barns, and garages. The test case trickled through the court system until 1942, when it was quietly dismissed.

After the war, the Outlaws made one last attempt to regain their early freedoms. In 1946, George Bogardus, who had flown from Bernard’s before the war, resurrected a small single-seat airplane that Lee Eyerly had commissioned as a prototype. Bogardus brought it back to flying condition and dubbed it Little GeeBee, perhaps after his initials (see “Barnstorming the Beltway,” Restoration, Apr./May 2006). In 1947, supported by coins, crumpled dollars, and lodging donated by fellow Oregonian pilots, Bogardus flew Little GeeBee across the country to take the case for amateur-built aircraft to Washington, D.C. There he lobbied the CAA on the importance of protecting the category of homebuilt aircraft from being regulated out of existence. Four years later, he made another such trip, and finally, the CAA wrote a regulation that permitted Americans to build their own airplanes and, after an inspection, license them in an “experimental” category—a plan very much like Oregon’s system. (For his efforts, Bogardus later became one of the first three people inducted into the Experimental Aircraft Association’s Homebuilders Hall of Fame. His Little GeeBee is now owned by the National Air and Space Museum, and it will be displayed later this year at the Museum’s Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in north-ern Virginia.)

Les Long’s airfield eventually reverted to farmland, although the current owner still works in the Outlaw-era buildings there and flies his Piper PA-11 from a short grass strip on the edge of the property. Ed Ball and Swede Ralston developed Hillsboro into a major regional airport, where Ralston, now 90, still comes to work every weekday—his office overlooks a large ramp filled with his charter company’s multi-million-dollar jets.

Charlie Bernard’s airport succumbed to economic necessity in 1969. Surrounded by residential and commercial development, the property became so valuable that hangar rents could no longer pay the taxes and expenses. Bernard sold the land to shopping mall developers, and drove his own bulldozer to knock down the hangars he’d built board by board almost 40 years earlier. Walt Rupert, who had flown and had operated a flying service at Bernard’s from the first day to the last, couldn’t bear to watch.

In 1978, John Patton asked Bernard how it had felt to put the blade against the hangars. Bernard paused for a long time, then said, “Did you ever want to cry, but the tears just wouldn’t come?” He died the following year.

Today, the Experimental category is one of the most vibrant of American aviation. Several hundred new amateur-built airplanes are registered—federally, of course—in the United States every year. An entire industry has evolved to supply homebuilders with kits, materials, and parts. The Oshkosh, Wisconsin-based Experimental Aircraft Association—Homebuilder Central—has 921 chapters across the United States, and dozens more in other nations. The Outlaws, says Carol Skinner, archivist of the Oregon Aviation Historical Society, “paved the way for pilots who could not afford production aircraft but wanted to have their own.”

Fittingly enough, today, some of the largest companies in the homebuilding field, such as Van’s Aircraft and Lancair, are based in Oregon—almost in the shadow of Bernard’s airport.