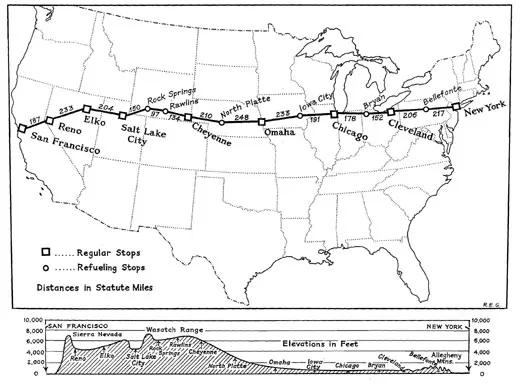

The Route: North Platte to Rock Springs

Pilots flying the mail cross-country in 1921 followed these directions to find landmarks along the way.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Platte-NASM-2B41470~A.jpg)

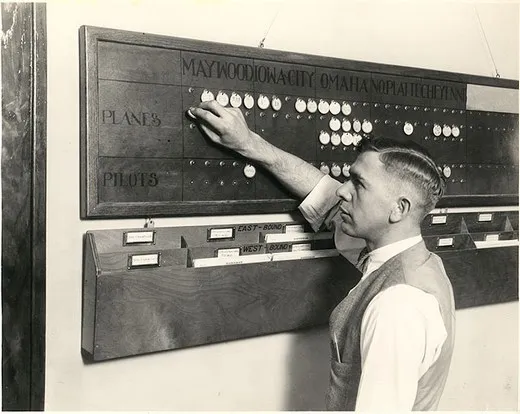

U. S. Air Mail Service

Pilots’ Directions (February 1921)

248. North Platte—After crossing the Union Pacific Railroad no distinguishing landmarks are available, but flying west the Platte River will be seen to the south, gradually getting nearer to the course. The city of North Platte is located at the junction of the north and south branches of the Platte River. The field is located on the east bank of the north branch about 2 ½ miles east of the town, just 100 yards south of the Lincoln Highway Bridge. Another bridge, the Union Pacific Railroad bridge, crosses the stream a mile farther north. The field is triangular with the hangar at the apex of the triangle and on the bank of the river. The field, which is bounded on the southwest by the river bank and on the north side by a ditch, has an excellent turf covered surface always in a dry condition. The field is longer east and west and the best approach is from the end away from the hangar. Cross field landings should not be attempted near the hangar, as the field is narrow at this point. The altitude of North Platte is 2,800 feet or about 2,000 feet higher than the Omaha field.

298. Ogallala—The south branch of the Platte River parallels the course to this point and the north branch is only a mile or two north of the course, veering gradually to the northward. The double tracks of the Union Pacific Railroad follow the course to this point. Fly directly west from this point, the south branch of the Platte River and the Union Pacific Railroad, veering to the southward.

338. Chappell—Two miles south of the course on the Union Pacific tracks and on the north bank of the Lodgepole Creek.

342. Lodgepole—Directly on the course between the Union Pacific Railroad and Lodgepole Creek. From here on to Sidney the course lies over the Union Pacific Railroad tracks and Lodgepole Creek.

360. Sidney—The Union Pacific double track runs through here east and west, crossed at right angles by the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad running north and south. Two miles west of Sidney the Union Pacific double track veers to the north, following the course of the Lodgepole Creek. The course, due west, lies from 4 to 6 miles south of the railroad and creek for the next 60 miles.

395. Kimball—Five miles north of the course on the Union Pacific Railroad and Lodgepole Creek.

420. Pine Bluff—On the Union Pacific Railroad 2 miles north of the course. The railroad and creek again cross the course, the railroad, turning westward to Cheyenne and the creek, continuing south for 4 miles and then eastward. The country between Sidney and Pine Bluff is the roughest on the whole course from Omaha to Cheyenne, but plenty of emergency fields are found. A ridge extends southward from Pine Bluff, on which numerous dark green trees may be seen. Two miles southwest of Pine Bluff the Union Pacific tracks are crossed and for 5 miles lie south of the course. Then another intersection of the course and the railroad looping to the northward and again crossing the course at the small town of Archer.

499. Archer—A small town on the Union Pacific Railroad and 8 miles from Cheyenne.

458. Cheyenne—Can be identified by the barracks of Fort Russell. The Cheyenne field is three-quarters of a mile due north of the town and due north of the capitol building, whose gilded dome is unmistakable. The field, though rolling, is very large and landings may be made from any direction. A pilot landing here for the first time must “watch his step,” as the rarified atmosphere at this altitude (6,100 feet) makes rough landings the rule rather than the exception.

Cheyenne to Rock Springs

Miles

0 Cheyenne—Fly west over or to the north of Fort Russell, which is about 4 miles from town, following the Colorado & Southern tracks to the point where they bend sharply to the north.

12. Federal—The first town on the Colorado & Southern Railroad after the railroad makes a sharp bend to the north. Fly about 6 miles south of Federal and leave the Colorado & Southern tracks about 1 mile north of the pronounced bend. The compass course, when there is no cross wind, is about 310˚. Cross Sherman Hills or Laramie Mountains at about 9,000 feet above sea level. Crossing this range of mountains the Laramie Valley appears, where landing fields abound.

40. Laramie—On the Union Pacific double-tracked railroad. The largest town in the valley. Pass 6 miles to the north of Laramie.

60. Rock River—On the Union Pacific, 20 miles north of the course. The double-tracked Union Pacific passes through 2 miles of snow sheds at this point.

80. Elk Mountain—To the north of the Medicine Bow Range, a black and white range of mountains, the black parts of which are forests and the white snow-covered rocks. Elk Mountain is 12,500 feet high. Fly to the north of this conspicuous mountain over high, rough country. The Union Pacific tracks will be seen about 15 miles to the north gradually converging with the course.

114. Walcott—Cross the S. & E. Railroad 2 miles south of Walcott. The S. & E. joins the Union Pacific at this point.

134. Rawlins—Follow the general direction of the Union Pacific tracks to Rawlins, which is on the Union Pacific tracks. The country between Walcott and Rawlins is fairly level, but covered with sage brush, which makes landings dangerous. Rawlins is on the north side of the Union Pacific tracks at a point about a mile east of where the tracks cut through a low ridge of hills. Large railroad shops distinguish the town. The emergency field provided here lies about 1¼ miles northeast of town at the base of a large hill. Landings are made almost invariably to the west. Surface of field is fairly good, as the sage brush has been removed. Easily identified by this, as the surrounding country is covered with sage brush. Landings can be made in any direction into the wind if care is exercised. Several ranch buildings and two small black shacks on the eastern side of the field help distinguish it. Leaving Rawlins follow the Union Pacific tracks to Creston.

159. Creston—A small station on the Union Pacific is the point where the course crosses the Continental Divide.

175. Wamsutter—On the Union Pacific. Fairly good fields are found between Rawlins and a point 60 miles west. Fields safe to land in show up on account of the absence of sage brush. The course leaves the railroad where the Union Pacific tracks loop to the southeast.

215. Black Butte—A huge black hill of rock south of the course. The Union Pacific Railroad is crossed just before reaching Black Butte.

231. Rock Springs—After passing Black Butte, Pilot Butte will be seen projecting above and forming a part of the Table Mountain Range. This butte is of whitish stone. Head directly toward Pilot Butte and Rock Springs will be passed on the northern side. The field is in the valley at the foot of Pilot Butte about 4 miles from Rock Springs. It is triangular in shape, the hangar being located in the apex. The surface of the field is good. The best approach is from the eastern side.

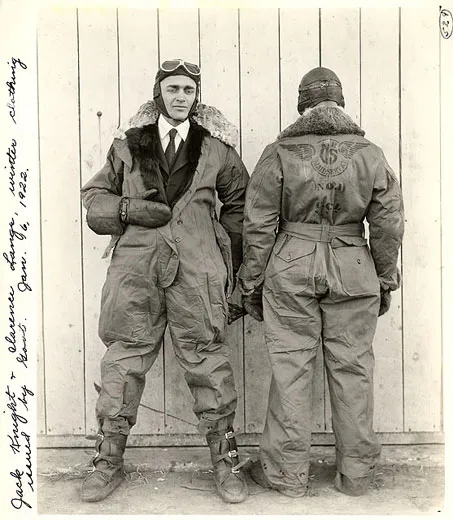

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/01.-SI-75-7024~A.jpg)