The Schneider Trophy

It began as the prize for a seaplane race. It ended as the symbol of a contest among nations that foreshadowed war.

On September 13, 1931, an aviation epoch came to an end. It was one of those rare days of English autumnal clarity, and the weather created a perfect setting for the vast crowds gathered on the beaches and cliffs of southern England to witness the last race for the Schneider Trophy. And because of a series of disasters that had befallen the competing Italian team, the onlookers knew the winner would be British. According to the rules, any competitor who managed to win the trophy three times in a row gained permanent possession of it. The Royal Air Force team, which had won the two preceding races, prepared to do just that for Britain.

It was a pity that the French and Americans had long since dropped out, but the important thing was that this was a chance to wave the Union Jack and cheer British triumph. It was a triumph that had been a long time in the making, one that might well have been celebrated by another nation, and one whose true measure would not be taken until the dark days of World War II.

The Schneider Trophy produced results its founder never would have predicted. Jacques Schneider launched the competition to foster development of commercial seaplanes, but he lived to see his original conception changed dramatically by the inexorable forces of international rivalry. The son of a wealthy French armaments manufacturer, Schneider loved high-speed boating and became a notable driver of hydroplanes. After meeting Wilbur Wright in 1908 he became passionately interested in aviation, but a crippling hydroplane crash two years later kept him from flying.

Given such experience, it is not surprising that Schneider thought to use his wealth to leave his mark on the aeronautical world, and do so in a way that combined his two great loves. He believed that in the future, nations would be linked by hybrid vehicles that had attributes of both hydroplanes and flying machines. His vision turned out to influence aircraft design for many years to come.

At the banquet following the fourth Gordon Bennett Aviation Cup race for landplanes at Chicago in 1912, he announced La Coupe d’Aviation Maritime Jacques Schneider. It would be an annual competition to encourage the development of practical aircraft capable of operating reliably from the open sea with a good payload and reasonable range. Schneider had no desire to spawn a family of freakish racing machines.

In light of later events it seems fitting that Schneider chose the Bennett banquet as the occasion for his announcement. The Gordon Bennett competition had been truly international, and by their very nature the races exerted political pressure on national authorities to become involved, sometimes against their better judgment. Simply put, while Bennett was there, it had to be won. When the French ended the competition in 1920 with their third successive victory, there was an almost official sigh of relief. But as the public’s attention turned increasingly to the Schneider, it became inevitable that the race should go to the swift rather than the practical.

The two pre-World War I Schneider Trophy races conformed to the founder’s intent: they were fought between aircraft entered by individuals or private companies. Most entries were hastily converted landplanes or were derived from existing designs. The races were suspended during the first world war, and by the time they resumed in 1919, the aircraft industries of the major powers, driven by wartime demands, had attained far higher levels of technological prowess. It did not take long for competitive flying to regain the place it had lost as the motivation for development, but until 1923 it seemed that Schneider’s dream would remain intact. The flying boats that dominated his race did indeed encourage the belief that the globe could be spanned.

The technology displayed at the Schneider races trailed the ingenuity of the aircraft industry, however, and there was little real competition. The Italians built the best flying boats, and other nations were not very interested in taking them on, even though by 1921 the winning speed was only 118 mph. Except for a disqualification in 1919 and the introduction of a chubby little British flying boat in 1922, the Italians would have won three in a row and so gained permanent possession of the trophy—a les than memorable victory, had they managed it then. Their failure saved the competition for greater things, and in 1923 the contest underwent an irreversible change.

The competition between the U.S. services in the early 1920s had produced a series of outstanding Curtiss racing biplanes—slim technological wonders produced by government funding, military rivalry, and public acclaim. Of far greater importance was the fact that the Navy team representing the United States’ debut at the 1923 Schneider race was composed of experienced, disciplined pilots and backed by a thoroughly prepared support organization. The Curtiss CR-3 floatplanes snagged first and second positions, with the winner, Lieutenant David Rittenhouse, averaging over 177 mph, a demonstration to Europe of the rapid strides U.S. aviation had made since World War I. The victor hosted the next competition, and now the Europeans had to face the prospect of competing on the other side of the Atlantic for the first time.

From then on, both flying boats and private efforts were outclassed. In light of such harsh realities, first the French and then the Italians decided to withdraw from the 1924 race at Baltimore. The British produced a promising contender known as Gloster II, but only five weeks before the race the little biplane porpoised savagely just after touching down, turned over in a wall of spray, and sank. With the last of the 1924 challengers gone, the U.S. Navy team could have flown sedately around the Baltimore course unopposed to claim their second win.

Given the extent of the U.S. preparations, which had also involved the loss of an aircraft, the despondent Europeans were astonished when the Americans canceled the race. The Royal Aero club at once cabled “warmest appreciation of the sporting action.” It ended up being much more than that. As things turned out, it could be argued that the magnanimity of the U.S. National Aeronautical Association prolonged the life of an extraordinary competition enough to indirectly influence events in the coming world war.

The British and Italians finally made it to Baltimore in 1925, and there were signs that they had learned lessons from their previous humiliations. U.S. dominance was correctly attributed to meticulous preparation by a professional team, fully supported in every way by its government. Although not yet prepared to go quite so far, the Air Ministry in London took first step and ordered aircraft from two companies for “technical development.” Gloster refined an existing biplane, but at Supermarine a young designer named Reginald J. Mitchell started from scratch.

Mitchell was till only 30 years old and virtually self-taught in aerodynamics, but he had been chief engineer at Supermarine for five years. He showed himself to be full of innovative ideas, as his first venture into floatplane design revealed. His Supermarine S4 was a beautifully proportioned midwing monoplane, and because it was known that wing bracing added considerably to an aircraft’s drag, he left the wings unbraced.

Regrettably, the S4 did not reach the starting line. During a trial flight severe wing flutter set in during a turn, and the aircraft crashed into the Chesapeake Bay. Mitchell was watching from the rescue launch at the time and was sure that the pilot, Henri Biard, had been killed. The designer was immensely relieved to see a very vocal helmeted head finally emerge from the water, but with typical Anglo-Saxon restraint he asked only, “Is it warm?”

With the S4 so dramatically removed, the U.S. team had little difficulty achieving its second victory. Lieutenant James Doolittle won for the U.S. Army, roaring home in his Curtiss R3C-2 at over 232 mph. The American public was looking forward to claiming the trophy permanently in 1926.

But the U.S. government was not prepared to support the rapidly escalating costs of any further development work, leaving the Americans with no new aircraft for 1926. Both Britain and Italy believed that because of the increasing complexity of the aircraft involved, the Americans would agree that it was only sensible to change the rules and run the contest every other year. However, with no funds available for further high-speed research, the U.S. authorities wanted to get Schneider competition over and done with. They insisted that the race be held as planned at Hampton Roads, Virginia.

The British stubbornly refused to believe that this was the last word, but Benito Mussolini saw an opportunity to show the world that nothing was too difficult for a Fascist state. He instructed the Italian aircraft industry to “win the Schneider Trophy at all costs.” In the early part of 1926, nobody in the aviation world gave the Italians the remotest chance of success, but Il Duce’s exhortations and money were wonderful encouragements to the nations aviation industry.

With no time available to develop original ideas, Italian designers sensibly set out to improve on the work already done by others. At Fiat they had studied the Curtiss engines and were sure that they could provide a racing engine that would deliver the necessary power. The airframe to be built around Fiat’s AS2 engine was entrusted to Mario Castoldi at Macchi. An intuitive aerodynamicist, Castoldi had a flair for absorbing and adapting the best ideas of others. He drew heavily on the lessons of the Curtiss racers and the Supermarine S4 in designing his M39, a firmly braced monoplane that had very clean lines and was obviously promising.

But before they ever left Italy, the Italians lost their captain in an accident. And after their arrival in the States, they were dogged by a series of carburetion oil-cooling snags that lead to an engine failure and two fires.

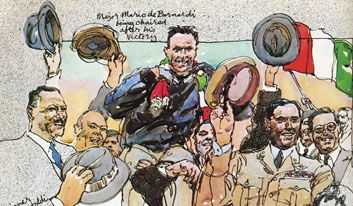

The U.S. team fared even worse. Its morale was badly shaken by the loss of three aircraft and two pilots in the last weeks before the race, and the limitations of the aging Curtiss biplanes were revealed when the Italian pilot, Mario de Bernardi, got his M39 to perform reliably. Bernardi won handily at over 246 mph, and his telegram to Mussolini said simply: “Your orders to win at all costs have been carried out.”

Ironically, the intervention of a Fascist leader ended up providing the British with another chance to get properly organized. The Air Ministry ordered new high-speed aircraft from three companies: Supermarine, Gloster, and Short Brothers. This positive step was followed by another: the chief of the Air Staff, swallowing his misgivings about full Royal Air Force involvement in racing, asked the elite RAF High Speed Flight team to represent Britain. The scene was set for the final act of the Schneider Trophy drama.

The last three races of the competition were held in 1927, 1929, and 1931, a general agreement having finally been reached that at least two years were required between races for proper aircraft development. In the States, many people felt that an attempt should be made to achieve a third victory, but the manufacturers had had quite enough of experimenting and longed for more profitable ventures. Neither the Navy nor the Army was prepared to set aside further funds for racing aircraft, and the United States never again raced for the Schneider Trophy.

The French, who since 1919 had managed to get only one aircraft as far as two laps around the seven-lap course, could not compete in 1927. In 1928 the government ordered two racing seaplanes from the Bernard and Nieuport-Delage companies and formed a racing unit of the Armée de l’Air. New engines were proposed by Hispano-Suiza and Lorraine, but the work that was done came too late for the 1929 race. Though development continued in the hope of competing in 1931, the French continued to lag behind. On September 5, 1931, after crashes destroyed two aircraft and killed one pilot, France finally withdrew.

It was left to the Italians and the British to fill the center of the stage during the contest’s closing years. The principal Italian standard bearer throughout was Macchi. For the 1927 race in Venice, the company drew on the success of the M39 to build the slightly smaller and even cleaner M52, with the goal of reaching 300 mph. The M52 was fast and good-looking but extremely temperamental. To compound the Italians’ misfortunes, team member Lieutenant Salvatore Borra crashed into Lake Varese while practicing and died.

The British approached the 1927 race with the first full backing of the government and the Royal Air Force. This meant that money was available to pursue several lines of research and development at once. The end product would be flown and supported by highly trained RAF personnel.

Mitchell had taken to heart the lessons of his ill-fated S4 and had seen the success of Macchi’s M39. Accordingly, the S5 wing was fully braced and also lowered to the bottom of the fuselage to increase the pilot’s field of view. Fuselage streamlining was improved, and the S5, much smaller than its predecessor, was expected to be up to 70 mph faster.

In many ways the 1927 race was less colorful than those of earlier years. Without private-venture entries, much of the silk-scarf dash seemed lost forever. There was no lack of excitement, however. The clash of two such professional racing teams mounted on purebred chargers was an exhilarating prospect.

The S5s justified their promise and finished first and second, the winner recording an average speed of almost 282 mph. The M52s were not as fast, and all three retired with engine trouble. Once the despondency of defeat was overcome, the Italians made determined preparations for revenge in 1929.

They had a number of weapons from which to choose. The Fiat C29 was an orthodox racing seaplane, but very small, having been built to take advantage of the firm’s new lightweight AS5 engine. The spectacular Savoia-Marchetti S65 had its tiny cockpit jammed in between tandem engines driving both tractor and pusher propellers; the tailplane was carried on twin booms. The revolutionary Piaggio PC 7, floating directly on its wings in the water, was urged onto its hydrofoils by a boat propeller. A clutch then transferred engine power to the air propeller for takeoff. Unfortunately, none of these aircraft was able to compete for the trophy. The C29 was destroyed in a crash, the PC7 was never able to rise out of the water and gain sufficient speed, and technical problems associated with the S65 proved too great.

In 1929, temporarily disgusted with Fiat’s engines, Macchi turned to an Isotta-Fraschini engine for its M67. This new marriage of airframe and engine proved irreconcilably unhappy. The pilots suffered from what they considered dangerous levels of exhaust fumes sucked into the cockpit while they were flying. The Italian team leader, Captain Guiseppe Motta, was killed when he crashed into Lake Garda at high speed, putting the Italians badly behind. The team arrived in England dispirited and sadly lacking in flying practice.

In England, Mitchell had decided that the reliable old Napier Lion engine had been pushed to its limit and a lot more power was needed. The only alternative was the Rolls-Royce. Earlier, the government had prodded Rolls-Royce into developing the Kestrel, insisting on a British engine to match the Curtiss D-12. Rolls’ managing director was not enthusiastic about aircraft engines, but the government again applied pressure, and the company finally agreed to cooperate. Starting with the Buzzard, a large relative of the Kestrel, Rolls-Royce produced the R engine, capable of turning out a reliable 1,900 horsepower, in only nine months.

Although similar in appearance to the S5, the S6 was noticeably bigger because it had to accommodate the R. It was Mitchell’s first all-metal aircraft, and to dissipate the great heat generated by its engine, it was covered with cooling panels. Well designed and meticulously prepared, the S6 inspired confidence among its RAF pilots. Then, at the eleventh hour, an incident occurred that could have handed the trophy to Italy.

On the night before the race, a Rolls-Royce mechanic changing the spark plugs in the leading S6 detected a tiny spot of white metal on one plug. The supervising engineer confirmed the likelihood of piston failure. The rules forbade and engine change at this late stage but allowed the replacement of parts. The entire cylinder block would have to be removed in some manner, but how? The job would take an army of technicians.

Finally, someone remembered that a party of Rolls-Royce fitters had come to town to see the race. Summoned from their pre-race celebrations, they rolled up their sleeves and set to work. Shortly after dawn the engine was given a test run. It performed perfectly.

The night’s efforts could not have been better spent. Both Italy’s M67s were forced to retire during the race and were replaced with the M52, the fastest of the Italian backups. The RAF’s second string was disqualified for missing a pylon, but Flying Officer H.R.D. Waghorn and the repaired engine won the race at over 328 mph, with the M52 finishing second.

Now, with final possession of the Schneider Trophy within its grasp, the British government, as its U.S. counterpart had done, found the cost of competing prohibitive. Withdrawing all support, it left the defense of the trophy to private enterprise. The government of the day was socialistic, so the situation was a bit ironic.

Throughout the following year the government stood firm under the withering attacks of the British press and public. With £100,000 needed to develop suitable aircraft and prepare for the race, it appeared that Britain would join the United States in walking away from the competition. Then, when all seemed lost, a fairy godmother made her entrance.

Dame Fanny Lucy Houston was the eccentric widow of a shipping millionaire, and she had two commodities in abundance: money and a hatred for socialists. When Lady Houston was not lambasting the government in her magazine, the British Saturday Review, she was proclaiming her revulsion at its practices by means of a large sign mounted on her yacht, Liberty. Early in 1931 she sent a message to the British prime minister that read in part: “To prevent the British Government being spoilsports, Lady Houston will be responsible for all extra expenses necessary beyond what can be found, so that Great Britain can take part in the race.” Later, when she made it clear that she would personally guarantee the entire £100,000, the government changed its mind and authorized the RAF to enter the race for the third time.

The Italians, meanwhile, were more determined than ever, and this time their efforts were concentrated behind Macchi alone. Mario Castoldi returned to Fiat’s fold for his engine, and Fiat’s response was dramatic. The company upgraded two AS5 engines and bolted them back to back to form a single power unit 11 feet long. This monster was supercharged to give a phenomenal 3,000 horsepower, and to house it Castoldi built the MC72, perhaps the ultimate in racing floatplanes.

Naturally, Mitchell wanted more power for the latest version of his aircraft, the S6B. Rolls-Royce obliged by boosting the R engine to 2,300 horsepower. The resulting combination was both fast and reliable.

In Italy, yet another tragedy was being played out. The MC72 was clearly very fast and its mighty new AS6 engine ran beautifully on the ground, but in the air it suffered from tremendous backfiring at speed. The Italian team persisted in flying it to pin down the trouble, and two aircraft and two pilots were lost in violent accidents. After pleading in vain for postponement of the race until 1932, the Italian authorities made the sad decision not to compete in 1931.

Final confirmation of the French and Italian withdrawals came only one week before the race day, and the British found themselves in the same predicament that the Americans had faced back in 1926. It was certain that the British government would not be coerced into competing again, particularly since Lady Houston’s magic wand was unlikely to wave more than once. It was now or never.

The plan was to fly both S6Bs. The first, piloted by Flight Lieutenant John Boothman, would fly the required seven laps of the Schneider Trophy course. Assuming success, the second S6B, flown by Flight Lieutenant George Stainforth, would attempt to break the world speed record over a straight three-kilometer course.

Shortly after 1 p.m. the R engine roared to life and Boothman moved off into open water. A few minutes later the slim silver and blue S6B dove for the starting line. Seven laps later, the song of the Rolls-Royce engine as strident as ever in his ears, Boothman flashed across the finish line to record a race average of just over 340 mph. The British had won the Schneider Trophy.

To cap an almost perfect day and send everyone home happy, Stainforth hit 379 mph, a world record for any type of aircraft. Two weeks later, using a sprint version of the R engine generating more than 2,600 horsepower, he raised the record to 407.5 mph, thereby becoming the first aviator to exceed 400 mph.

Persistent even in defeat, the Italians invited British fuel wizard Rod Banks to advise them on carburetion in the AS6. He concocted a fuel mixture that the engine seemed to enjoy, and by 1934 the MC72 raised the world speed record to 440.681 mph, a figure that, for floatplanes, stands to this day.

With the achievements of the S6B and the MC72, the era of great international air racing came to an end. Jacques Schneider’s dream of world-shrinking “hydro-aeroplanes” had been realized in the very racing freaks he had wished to avoid promoting, but even he would have been impressed by the progress made in less than two decades. The best of the earliest racers, the Sopwith Tabloid, was flat out at 92 mph. Less than 20 years later the MC72 proved almost five times as fast. The standard Gnome Monosoupape rotary of 1913 weighed 250 pounds and produced 100 horsepower. Rolls-Royce’s R engine weighed more than six times as much but was over 26 times as powerful.

Of the four principal nations involved, France got the least out of the competition. The United States changed the character of the race and administered the shock that stimulated the rapid advances made in both Britain and Italy. But after the U.S. withdrawal in 1926, it began to lag behind Europe in development of engines and airframes for long-range, high-speed fighters.

The Italians gave the most in their determination to win the “Coppa Schneider.” They submitted entries for more races than anyone else, their designs were frequently the most imaginative, and they lost the most pilots—seven in all between 1922 and 1931. Ironically, the marvelous Fiat engines were forgotten, and in 1941 Castoldi had to turn to Germany to find a liquid-cooled engine for his fighters.

The British made the most of their experience. Mitchell’s work on the low-wing monoplane form, begun on the S5s and S6s, eventually led to the superb Spitfire. The Rolls-Royce R engine fathered the illustrious Merlin, which powered not only the Spitfire but also the Hurricane, Lancaster, Mosquito, and, as persuasive evidence of the effect of the U.S. withdrawal, the P-51 Mustang.

The effect of the competition, though, extended beyond the creation of just one engine. During this period, supercharging evolved into a fine art, and consequently, from the outset of the coming world war, aerial combat would routinely be carried out at altitudes considered remarkable only 20 years earlier. It might even be argued—and has been—that the very existence of new supercharger compressors enabled Frank Whittle to develop his turbojet.

Exotic fuel “cocktails” mixed by brilliant individuals like Rod Banks established the formula for volume production of aviation gasolines with anti-knock properties; these fuels enabled supercharged, high-compression engines to run at high power settings without the risk of detonation. Even the advancement of techniques for liquid cooling led to markedly higher fighter performance by the second world war.

Brute power alone would not have resulted in high speeds without parallel advance in the principles of drag reduction. Here, the Schneider Trophy races may have made their least recognized contribution. The earliest racers were bluff and squarish, but by the series’ end the airplane had been transformed into a sylph that barely distributed the air in passing. The fact that airplanes encumbered by huge floats could have attained more than 400 mph in 1931 is sufficient testimony to the competition’s role in the education of aerodynamics.

The Schneider Trophy trail was a strange and tortuous one. In encouraging the talents of such men as Reginald Mitchell and the Rolls-Royce engineers, the competition may not have remained true to Jacques Schneider’s conception, but it did lay some of the foundation upon which the Royal Air Force built its victory against the Luftwaffe in the Battle of Britain.

This article first appeared in the June/July 1988 issue ofAir & Space/Smithsonianmagazine.