The Seven

In 1959, a group of military pilots became Astronaut Heroes overnight, and created an American icon that survives to this day.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Mercury7-flash.jpg)

We must screen our personnel to find those … who have demonstrated … coolheadedness and resourcefulness in tight situations, who have good intelligence, who can tolerate various extremes of physical punishment, and who are stable, calm, and confident. We must reject those who, although able to give a good account of themselves, do so primarily to prove something to themselves or the world. Then we must narrow this select pool of potential satellite pilots down to those six to ten who are best fit to undertake such a mission.

—USAF Brigadier General Don D. Flickinger (1955)

Fifty years ago this month, amid great secrecy, the United States chose its first astronauts: military test pilots willing to risk their lives and promising careers for a chance to orbit the Earth in a metal compartment the size of a phone booth. America had barely begun to launch robotic probes (and the occasional monkey) into space, but in its contest with the Soviet Union, there would be no substitute for human exploration. The men America selected for this mission would become a new kind of professional and a new kind of celebrity, defining both the program in which they served and the public’s idea of what an astronaut should be. We still live in the Space Age they helped create.

Throughout the 1950s, military test pilots, often working with the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, had flown experimental aircraft in the skies above Edwards Air Force Base in California and the Naval Air Station at Patuxent River, Maryland. A lucky few would soon scrape the edge of space, and by 1955, Air Force Brigadier General Don D. Flickinger already knew what kind of people he wanted for the job: quick-thinking aviators who would put the mission first. In time, the Air Force hoped, one of its own would become the first human to pilot a craft through space: one with wings, flown by a coolheaded man in blue. The Soviet Union’s 1957 launch of Sputnik atop a huge, belching, liquid-fuel rocket not only altered the Air Force’s plans, but set in motion a chain of events that ended in the creation of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, a new civilian agency in charge of America’s first human spaceflight effort.

NASA’s first moves toward recruiting a professional astronaut force were abortive: in December 1958, the Federal Register Robert R. Gilruth, had begun leaning toward the kinds of military test pilots the Air Force had already scrutinized, people who NASA could recruit in secret, and whose previous assignments made them amenable to risky technical work.

To NASA’s surprise, President Dwight D. Eisenhower agreed: America needed a public, open space program, but it needed it fast. No one had to say it out loud, but none of America’s new astronauts would be women or ethnic minorities: Among trained military test pilots with jet experience, there weren’t any, at least not yet.

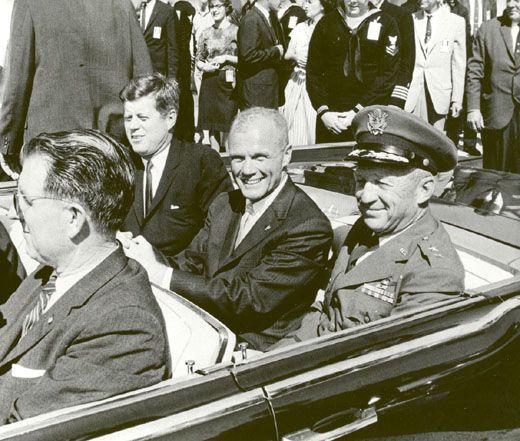

Whether the seven Air Force, Marine Corps, and Navy officers NASA selected as astronauts in April 1959—Scott Carpenter, L. Gordon Cooper, Jr., John H. Glenn, Jr., Virgil I. “Gus” Grissom, Walter M. Schirra, Jr., Alan B. Shepard, Jr., and Donald K. “Deke” Slayton—had actually volunteered for the job is a question about which some of the men later joked. NASA, though, only wanted the willing. Some of the invited pilots were skeptical, but each thought he was the best for the job. If anyone was going to become an astronaut, one later wrote, it might as well be him.

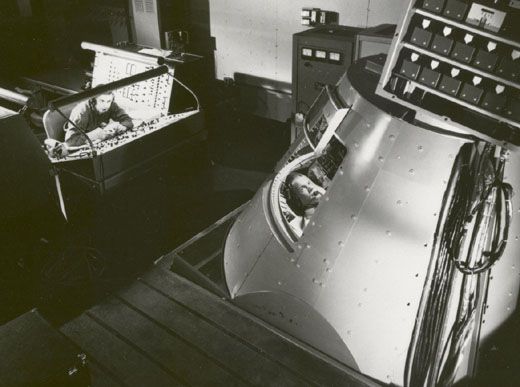

Of the 110 pilots NASA’s Screening Committee invited to Washington for initial interviews, so many responded enthusiastically that the agency stopped the interviews after the first 69 candidates had dropped by. Psychological testing accompanied the feelers, followed, for a select few, by detailed medical examinations so new that many of the physicians weren’t quite sure what they were looking for.

The men NASA screened were rising stars; for them, America’s new, untested space program was a professional gamble as well as a physical one. Organization men at the top of their game, they had questions. Were there opportunities for advancement? Would they actually get to fly their machines in space as pilots? As first, it seemed likely that they wouldn’t: early Mercury spacecraft were brilliantly engineered but largely autonomous, and the pilot would be little more than a passenger. Senior test pilots scoffed in disgust; more junior ones, like the men invited to Washington, saw an opportunity. Just maybe, some thought, they could turn the odd little capsules into true spacecraft, applying their skills to make vehicles they actually wanted to fly. NASA—Gilruth especially—encouraged their efforts.

Air Force psychiatrists gushed over these bright, educated pilots, who conversed with confidence, spoke of their families, and developed an instant rapport with almost anyone they met. The astronauts were on their best behavior, to be sure, but the description wasn’t too far off the mark. Expecting to find adolescent thrill-seekers, examiners were surprised to find, instead, the occasional nerd or dreamer, but mostly working engineers: a little dull maybe, but reliable.

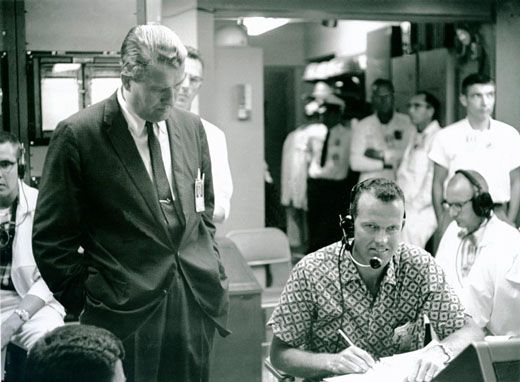

Introduced to the public in a press conference on April 9, 1959, the spacemen smiled and spoke of machines and procedures. NASA’s new astronauts wondered what all the fuss was about: they had done nothing to earn the public’s trust, and had a lot of work ahead of them in a space program still unsure of the pilots’ role. For NASA management, though, the men were the glimmering heroes it desperately needed to deflect questions about America’s lagging race with the Soviet space juggernaut. And to the press, the pilots were the pure sons of America, willing to give their lives for freedom when not attending their local church or kissing their children goodnight.

The biggest surprise of the first astronaut selection was not how the men would ultimately do in space (some performed better than others, but all did well), but how well most of them navigated the tricky politics of planetary celebrity. Each day, NASA asked more of its space pilots, and the men responded, brilliantly. America in the 1960s loved its astronauts, and for good reason: they remained so enigmatic that they easily absorbed whatever popular fascination Americans chose to project upon them. The same men who had appeared to the public as Cold Warriors in 1959 had become spiritual adventurers by 1969, and by 1979, in Tom Wolfe’s telling, fun-loving fighter jocks. The astronauts took it all in stride.

The choice of military test pilots was a fateful one for the American space program. The astronauts arrived ready to work, with clear ideas of what space vehicles should look like and how to fly them. In an endeavor as dangerous as combat, the astronauts showed calm in claustrophobic craft, and their skill undoubtedly enabled the staggering American space achievements of the late 1960s, including the first landings by humans on the Moon from 1969 through 1972. (One of the Mercury selections, Shepard, was among the twelve people to achieve this feat.)

By choosing men of such peculiar skills, however, NASA allowed the pilots to embed their own unique culture firmly within the agency. Would our image of astronauts be different today if we’d sent civilian mountain climbers and deep-sea divers to explore space, instead of military officers? We’ll never know. But when NASA later broadened its astronaut ranks to include scientists and other non-pilots, the old hands and the rookie astronauts bumped heads, competing for scarce seats on space shuttle flights.

NASA’s astronaut corps, 50 years later, is every bit as skilled as the one the agency recruited in 1959—probably more so. It is also more diverse, by sex, by ethnicity, and by education. Ask any American what an astronaut looks like, though, and they’ll likely conjure up a member of the “Mercury Seven”: all business, and ready to take on the universe.

Matthew Hersch, a Ph.D. candidate in the University of Pennsylvania's Department of History and Sociology of Science, was the 2007–08 Guggenheim Fellow of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Air and Space Museum. He is presently writing a labor history of American astronauts.