The Smithsonian’s Hollywood Moment

The makers of Night at the Museum took great pains to get it right.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/NightatMuseum-flash.jpg)

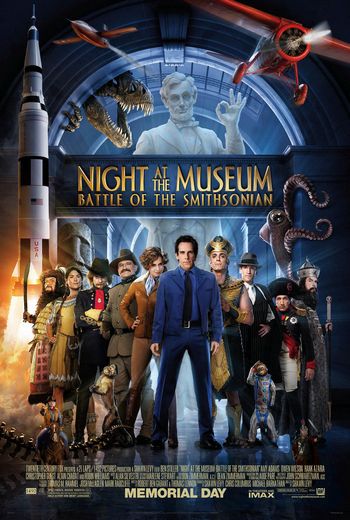

In the 2006 film Night at the Museum, security guard Cecil Fredericks (played by Dick Van Dyke) tells Ben Stiller’s character, Larry Daley: “Kids don’t care about wax figures and stuffed animals.” Fortunately, he was wrong—at least when the wax figures were Attila the Hun, President Theodore Roosevelt, and fire-obsessed Neanderthals. The wildly popular movie made more than $570 million worldwide, enough to spawn a sequel, Night at the Museum: Battle of the Smithsonian, which opens nationwide on May 22.

In May of last year, the new film’s crew, actors, and hundreds of extras descended on the National Air and Space Museum for filming. (They also shot scenes in the Smithsonian Castle and the National Gallery of Art, and on the National Mall.) While NASM curators were sworn not to reveal the movie’s plot, a Amelia Earhart and Orville and Wilbur Wright will be among those who battle it out in the Nation’s Attic.

What did the real-life Smithsonian staff think of the film? After the shooting wrapped up in Washington, director Shawn Levy asked curators Margaret Weitekamp and Bob van der Linden, along with NASM communications director Claire Brown, to visit the set in Vancouver, Canada, where the studio re-created one of the world’s most popular museums.

“They did a great job,” says Weitekamp, a curator in the space history division. “The National Air and Space Museum is really a character in the movie, and they had taken the time and attention to replicate it in great detail. They even got the railings in the stairwells right. The National Mall building has brass handrails that have gotten a little dull on the top by virtue of millions of visitors running their hands up and down them for 30 years now, and they actually replicated that.”

The film crew also wrote labels for all of the artifacts. “That really impressed me,” continues Weitekamp. “I really expected that the labels would be the kind of Latinate gibberish that you use when you’re laying out a book—dummy text, basically. And it was real text. Someone had done research on the objects—and in between takes, the cast and crew would wander around reading the labels and learning about the history of the various aircraft and spacecraft.”

“It was the first time I’d been on a major Hollywood set,” says van der Linden, chairman of NASM’s aeronautics division, “and it was a lot of fun watching how they did things. We walked into this room, and we thought it was a proper museum-quality warehouse. And it was a set! Their inspiration was the Museum Support Center and our Garber facility. I leaned up against what I thought was a concrete pillar, only to find out it was fiberglass. It was very believable.”

During shooting on the Mall, he recalls, the film crew sometimes worked up to 3:00 in the morning. “If they were shooting inside the building, anywhere near objects, there was someone here to watch over it,” he says. One of those people was museum specialist Anthony Wallace of the collections processing unit. “The crew was so willing to work with us,” says Wallace. “They understood that these weren’t movie props but actual historic artifacts that should be treated differently than their own props.”

After the crew set up their equipment, Wallace would evaluate the position of the lights, sometimes requesting changes. “They would happily move something, and were interested in learning why, so I would explain what the object was, and the danger the light would pose to it.” For example, a light had to be moved from the old Curtiss JN-4 “Jenny” in the America by Air exhibition because the heat from the lamp might have ignited the nitrate in the dope used to treat the fabric. Another lamp had to be positioned away from the human-powered MacCready Gossamer Condor for fear that the aircraft’s Mylar covering would melt. “Also,” says Wallace, “we needed them to cover up a couple of exhibit cases containing a jacket and a hat that weren’t going to be in the shot but would be affected by the light. The hat was red, and the light was basically shining right on the case. It was a loaned object, and we didn’t want it to go back pink instead of red.”

“It was amazing how many people were actually involved in the whole [filming] process,” says Wallace. “They brought in a crew of about 100 people and had about 120 extras as well, and there was a lot more equipment than I thought was used when making a movie. They had all different sizes of lights, different outputs and filters, and miles of cable. It was interesting to think, too, that it was probably only going to be about five or 10 minutes in the actual movie, and they took three days to shoot.”

Loren Plotner and the rest of the Office of Facility Management and Reliability put those miles of cable to good use, working both inside and outside the Museum, making sure the crew had all the power they needed, and that the building’s exterior lights were working for the night shots. Plotner was impressed with the movie crew: “They worked very well together, kind of like a married couple that’s been together long enough they don’t even have to speak.”

The producers gave Weitekamp and van der Linden copies of the script to help them prepare for the onslaught of visitors. “Starting this summer,” says Weitekamp, “we’re going to have visitors coming in who think they’ve seen this Museum. And they’ve seen some pieces that were filmed in the three days they did actual shooting on the Mall, and an awful lot that was on a soundstage in Vancouver. What’s exciting for us is that people are going to see the Smithsonian and the National Air and Space Museum and the Castle as characters in this movie, and then perhaps have some renewed interest in coming here to see the real thing.”