The War Between the Wars

In the skies over Spain, pilots and airplanes rehearsed for World War II.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Arch_Chato_SpanWar_Flash_AM09.jpg)

At the Cuatro Vientos airport on the outskirts of Madrid, a small party has gathered at the Infante de Orleans foundation's aviation museum to celebrate a new design by a local watchmaker. The timepiece is named Mosca, for a Russian-built fighter that flew in the Spanish Civil War 70 years ago. Later that day the watch will be presented to the airplane's most famous pilot, José María Bravo Fernández-Hermosa.

On this fine autumn Saturday, both man and machine are here. As he often does on such occasions, José Bravo poses for photographs beside the olive-drab Mosca, which wears his old aircraft number, CM-249, and the seis doble—the double-six domino tile—painted on its vertical stabilizer.

The veteran ace absorbs the attention with the ease of a rock star. Affable and a bit frail at 91, he likes an arm to hang onto while the cameras flash, but it's no stretch to imagine him in this muscular little airplane. Still wearing a lapel miniature of his red-star wings, he is one of a handful of living fliers who were present when World War I met World War II in Spanish skies.

Bravo's war began in July 1936, when much of the Spanish army, led by a junta of generals, rebelled against a newly elected popular front government, a volatile coalition of liberals, communists, workers, anarchists, and separatists. The army-backed Nationalist side comprised fascists and their blue-shirted counterparts in the Falange party, along with monarchists, the aristocracy, and the Catholic Church.

Fearing a European war or a Russian-style revolution, the League of Nations decided against intervention, leaving the new Spanish government to defend itself and both sides to wage war with limited military means, particularly when it came to aviation. The Republican government's air force was a creaking assemblage of the old and slow. And even though the Nationalists controlled the army, their air force was virtually nonexistent.

Both sides also suffered a dearth of pilots, but most of the veteran military pilots remained true to the army and quickly sided with the rebels. Joaquín García-Morato Castaño, for example, was already one of Spain's most accomplished pilots when the war began. At 32, he had accumulated 1,860 hours and flown against Moroccan insurgents. Fighting on the Nationalist side, he would lead the potent Patrulla Azul (Blue Patrol) and emerge as the conflict's top ace, with 40 confirmed kills.

Only a few pilots stayed with the government. If the Republicans wanted an air force, they would have to create it from a legion of young men who had never left the ground.

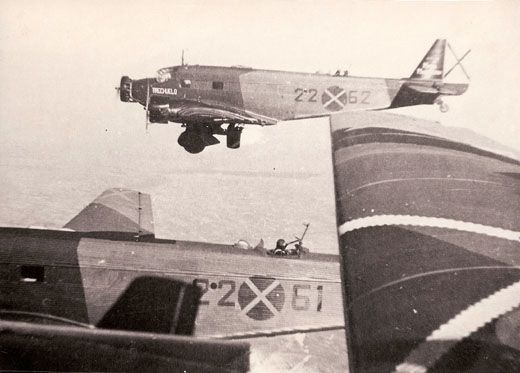

First, though, both sides turned to outsiders for help. Despite their official neutrality, Hitler's Germany and Mussolini's Italy both quickly came to the aid of the fascist-leaning rebels. Italy supplied a dozen Savoia Marchetti SM.81 trimotors. Manned exclusively by Italian crews, the low-wing Savoia transports spent the war doubling as bombers. The first German "package," code-named Magic Fire, was on its way within weeks of the war's start. Twenty Junkers Ju 52/3m transports arrived by ship, along with half a dozen Heinkel He 51 fighter-bombers and tons of spares, ammunition, and anti-aircraft weaponry. Nearly 100 German airmen were also on board as "vacationers."

By early August, the Ju 52s had flown 1,500 veteran troops from Spain's Army of Africa to the mainland in history's first major military airlift. With them came General Francisco Franco, who set up headquarters in Seville. Over the next few weeks, the Junkers and Savoias brought another 20,000 or so Army of Africa troops past the Mediterranean naval blockade. Franco emerged as leader of the Nationalist rebellion, but not of Hitler's air forces. The latter were quickly placed under German command, constituting a mini-Luftwaffe in Spain: the Condor Legion.

"None of us knew that the German Volunteer Corps in Spain went by that name," Luftwaffe ace Adolph Galland would write in The First and the Last. "We only noticed that one or another of our comrades vanished suddenly into thin air…and that after about six months he returned, sunburnt and in high spirits."

Galland became a Condor Legion legend, flying in swimming trunks, a cigar clamped in his teeth, his face blackened by gun smoke and engine oil. Leading the Mickey Mouse squadron (named for its pistol-toting rodent insignia), he honed the ground-attack abilities of the He 51. He developed carpet bombing to flush miners from caves in the northern province of Asturias, and, with his mechanic, brewed up a bomb called the flambo—a precursor to napalm.

Italy's air corps in Spain was known as la Aviazione Legionaria. With the Italian pilots came more trimotor bombers, along with Meridionali Ro.37 ground-attack biplanes. Italy's main gift, however, was the highly maneuverable, potently armed Fiat CR.32, which in Spain was called the Chirri.

Help came to the Republican side as well. Josef Stalin agreed to provide men and matériel, although not entirely for love. Airplanes were available at retail prices, to be paid in Spanish gold. By mid-October the Soviet Union shipped 30 SB-2 Katyushka (Little Kate) fast bombers. Designed by Andrei Tupolev, they were smooth-skinned, with a low cantilevered wing and two big Wright-Cyclone-type radial engines. These were joined by the agile Polikarpov I-15 Chaika (Seagull, for its gull-like upper wing), which the Spanish would call Chato (Snub-nose), and Polikarpov R-5s and R-Zs, which were used for reconnaissance and light bombing.

Then, in early November, Spain received the first Polikarpov I-16 monoplanes. In an age of two-wingers, this speedy fighter had a single, low, cantilevered metal wing and retractable landing gear, plus a 1,000-horsepower radial engine up front. The I-16 was called Yastrebok (Hawk) and, at home, Ishak (Little Donkey). In Spain it was called Mosca (Fly) by its friends, Rata (Rat) by its enemies. By any name, the I-16 was at the time of its debut the most advanced fighter ever sent into combat.

Soviet volunteer pilots came over even before the airplanes arrived, and soon were given Spanish noms de guerre. Yakov Smushkevich became General Douglas, Colonel Pyotr Punpur became Colonel Julio, fighter group commander Pavel Rychagov, Pablo, and so on. By late November, 300 Soviet pilots were flying for the Republican side, which, having lost the early air war, soon fought back to reclaim the sky over Madrid.

Volunteers from other countries also flocked to the Republican cause. Eager to fight against the fascist rebels, the French writer André Malraux came over with a gaggle of lumbering Potez Po.540 twin-engine bombers—familiarly, "flying coffins." Although he never piloted an airplane, Malraux survived more than 60 missions. But his involvement in the war was short-lived. By January 1937 the flamboyant polymath was gone, and more than half of the several dozen Po.540s sent by France had been destroyed.

The first American volunteers arrived in late September 1936, followed by another contingent in November, and a third near the end of the year. Ideology was less important to this group than it had been to Malraux's. Most thought the cause was okay, and $1,500 a month and $1,000 for every Nationalist airplane destroyed was good money. Ben Leider, the New York Post "flying reporter," was the only Communist, and the only one working for regular officer's wages, like his Russian and Spanish counterparts. Not long after his arrival, he was killed by CR.32s from Morato's Patrulla Azúl.

The American volunteers were better at aviation than at life. Frank Tinker, whose memoir, Some Still Live, would make him briefly famous, was typical: Annapolis graduate cashiered from the Navy for bad behavior, traveling on a passport issued to one "Francisco Gomez Trejo" (who, unaccountably, spoke no Spanish). Tinker's fellow volunteers included aviators of fortune, barnstormers, bootleggers, and thieves. But Tinker, the aw-shucks Arkansan with a taste for drink, women, fighting, and flying, became the mercenaries' historian.

He flew for the Escuadrilla de Chatos, commanded by Andrés García Lacalle, who, at the age of 27, had already downed 11 Nationalist aircraft. Lacalle organized his unit into three "patrols" of four aircraft each, with Tinker and three other Americans known as La Patrulla Americana. In early February 1937, the squadron moved to a field near Guadalajara, northeast of Madrid. There the Americans got their first look at the Russian I-16. Failing to recognize the new face of aerial warfare, Tinker thought the aircraft was a knockoff of the Boeing P-26 Peashooter.

Guadalajara was the scene of the Republican pilots' finest moment. In early March 1937, word came that a massive Italian force was advancing on the city. Harold "Whitey" Dahl, another American, took his Chato up into the soggy weather on an armed reconnaissance mission. Tempting the Italians with a low pass, he discovered they were paralyzed by flooded roads and washed-out bridges, and had little anti-aircraft defense.

As soon as the rain let up, Lacalle scrambled his Chatos, each aircraft laden with 18-pound bombs. Dropping under the low ceiling, the squadron found and attacked the Italians. It was the only unit on either side flying that day, for the rains had turned most airfields into bogs. Lacalle's had been planted in alfalfa, which kept it usable.

As the weather lifted, scores of Republican fighters and bombers attacked the Italians again. With staggering losses of men and matériel, the advance stalled. It was the first time in history that air power had stopped a major ground offensive.

Between fights, the pilots could enjoy hot baths and an endless party at Madrid's Hotel Florida, where they befriended Ernest Hemingway and other journalists. Hemingway's short story "Night Before Battle" has a pilot called Baldy who is modeled on Dahl.

But even as the Republican aviators seized the initiative, the era of volunteers was winding down. Tinker and another American, A.J. Baumler, moved to a Soviet Mosca unit. Before the summer ended, they would head home. The Republicans would fight most of the air war with brand-new Spanish pilots, trained in Russia.

At the Madrid offices of the Association of Republican Aviators, or ADAR, the walls are decorated with posters, maps, and black-and-white photos of pilots and airplanes—most of them long gone. The shelves are lined with wooden models of Spanish Civil War aircraft. The association's insignia, the red star and wings, is everywhere.

The walls also bear color photographs of an early ADAR reunion, held at Cuatro Vientos in 1972. The association began during the last years of Francisco Franco's dictatorship, with clandestine meetings of former Republican airmen. The members still get together annually, and the organization now includes non-combatants.

"The reunions are important," says Marie Carmen Martin, who runs the office. "They bring people together from around the world to meet and to help one another." Like many in the ADAR community, she is a veteran once removed: Her father was a Republican aviator. "It's my family," she says. "My life." The organization lives on contributions, receiving no government support for its activities.

Each year there are fewer members who can recall arriving in the Azerbaijani city of Kirovabad in January 1937 as part of the first "expedition" of young Spanish men selected for flight training in Russia. One who remembers is José Bravo. "We put on Soviet uniforms," he wrote in 2007. "Our mission was ultra-secret and no one was to know that they were bringing in Spaniards. They gave all of us Russian names. I was Iosif Bravi."

After six months of training (starting in the docile Polikarpov U-2 biplane), Bravo had logged about 100 hours, only a few in the I-16. Back in Spain by summer, the new aviators went to high-speed school, then, still relatively green, to a Soviet Mosca squadron in the north, and combat. The Russian and Spanish pilots stood alerts beside their fighters on grass fields, waiting for the flares that signaled a scramble. After a few times around the field, said Bravo, "We'd head off to look for the enemy."

By then the enemy was easy to find: Swarms of next-generation German warplanes had entered the fight. The bitter winter battle of Teruel, in the mountainous region of Aragon, was the most savage combat of the war. In January 1938, Republican forces were nearly destroyed by a Nationalist counter-attack. Casualties on both sides ran to the thousands, with devastating losses in the air.

In the ADAR office's main room, Gregorio Gutiérrez García sits at a large table. Now 91, he was part of the second expedition to the Soviet Union, going over in late 1937. At the Spanish airman's school in Kirovabad he was Gutin Gregoriev, or "Guti." He returned to Spain in mid-1938.

Before going to the Soviet Union, he had fought on the Madrid front with the International Brigade. Did that mean he was political?

He shakes his head emphatically. "The first expedition was political. The second was not. I did not take part in communism."

Joaquin Calvo Diago comes in, very thin in a blue suit and sweater, his skull evident beneath the skin. He has a huge grin and his memory is crystal clear. He was in the same expedition as Gutiérrez, but went to Chatos, not Katyushkas. He was called Yokuv Calvin.

Was Calvo political?

He makes a face and shrugs. "I was a kid. I knew nothing." But he liked the training. "Three months at the Soviet school was better than three years in the Spanish one."

Guti and Calvo joined the fight in late summer 1938, and by the end of that year, not a single Russian pilot remained in Spain. "When we were ready, all the Soviet pilots went home," Calvo says. "Italians had complete units, Germans also. But by now the Republican pilots were all Spanish."

With the Republicans still reeling from the disaster at Teruel, Franco launched an offensive aimed at slicing off Catalonia, on the French border, from the rest of the country. All of the Condor Legion's Heinkel He 111s, Dornier Do 17s, and Heinkel He 51s were dedicated to the attack, along with something new: the Junkers Ju 87 Stuka dive-bomber, in combat for the first time.

Republican forces were driven southward along the Ebro River. A daring counterattack beginning in July 1938, staged with little protection from enemy aircraft, lasted bravely for four months before ending in defeat. It was the government's last major offensive against the fascist rebels.

Calvo, who came to lead the Republican fighter forces, still feels fond of the little biplane that got him through the war: "The Chato is simpático"—nice. "The Mosca," and his hands pretend to haul back on a heavy wheel, "very hard; stronger." The Chato—more hand gestures—"was very maneuverable against the 109 [the Messerschmitt Bf 109]. It climbed well." His Chato hand moves around behind his Messerschmitt hand and takes an imaginary bite. Another big grin.

Gutiérrez prefers his beloved Katyushka. In a remembrance for the ADAR publication Icaro, he described the life of a bomber crew in the final days of the war. "The fourth escuadrilla of Katyushkas was active on every front, Teruel, Segre, Extremadura, Levante, and, of course, the Ebro. We flew almost daily, often in the morning and afternoon, without break," he wrote. Over Catalonia, "[t]he air space we had to cross was a veritable curtain of smoke and fire…. To penetrate this space, one needed well-tempered nerves. To get out…the only thing you needed was baraka...luck."

The Katyushka carried a crew of three—pilot, observer, and gunner—and had machine guns above and underneath the aft fuselage. The gunner could use both, but not at the same time; when he was on the upper gun, the Katyushka's underside was unprotected.

During a September 2 raid in the western province of Extremadura, one of the three-airplane patrols in Guti's harried Katyushka squadron became separated. Smelling opportunity, a Nationalist Fiat CR.32 dropped into position behind the bombers and took them down, one-two-three. By the time the Mosca escorts saw what was happening, the Katyushka crews had bailed out, only to be shot as they floated to Earth, or gunned down on the ground.

"Besides the powerful enemy," Gutiérrez wrote, "we also had another inside the house. When we flew any mission, we had to examine the parachutes, which were almost always sabotaged. The espionage service had information on everything. When we left, they knew in advance the date, hour, altitude…even what we had for breakfast."

What kind of targets did he hit?

Guti replies forcefully: "I never bombed a city." He doesn't need to elaborate: The German and Italian pilots' bombing of the Basque city of Guernica on April 26, 1937, remains the air war's most infamous act, immortalized by a Pablo Picasso painting. Only once, says Gutiérrez, did Republican bombers hit a concentration of guardia civil, holed up in Avila. "The Germans always sent their planes against civilians. Also the Italians."

José bravo's civil war ended at Vilajuiga on February 5, 1939, 10 days after the fall of Barcelona and less than two months before the Republican surrender. The plan was to take the Chatos and Moscas that could still fly and head for France. Bravo still has the letter authorizing the pilots to abandon Spain.

Some Chatos took off the following dawn. Then German bombers, escorted by Bf 109s, attacked the field. Bravo narrowly escaped his burning Mosca, but all his documents, including his flight log, were lost.

After the bombers rumbled away, a single "Messer" remained, staging an aerobatic show while strafing. Something—Bravo thought it must be ground fire—hit the German fighter, which fell out of a loop and plowed into the ground.

Another pilot, Francisco Tarazona, wrote a vivid account of what followed: "From the wreck of the downed Messerschmitt…the German pilot staggers away…. Wisps of smoke issue from his flying suit…. 'Kill me!' he cries…. Arias [another Mosca pilot] gets his pistol out.

" 'What are you going to do?' roars Bravo.

" 'Kill him! To put an end to his suffering,' " Arias replies, cocking his pistol.

" 'No! Let the bastard rot.' "

As they move away, Arias suddenly turns back. "He points the barrel of his pistol at the poor man's eyes, then fires one shot between them."

With no airplanes to fly, Bravo and his companions crossed the Pyrenees on foot. They were captured and interned in a camp at Gurs, just over the border in France. "The French tried to enlist some of the hundred or so pilots into their colonial army," recalled Bravo, who refused. "Better to be the last of the Republicans."

When the Soviet Union offered the pilots a Russian future, however, most were quick to accept. But Fernando Medina was among those who escaped and returned to Spain to await his fate. The crews were told that their aircraft were to be handed over to the Nationalist victors at Barajas, Madrid's major airport. On March 29, nine Katyushkas took off from the Republican base at San Clemente, along with six more from Tarazona, 12 Chatos, and a score of Natashas (Polikarpov R-5s).

"We landed in Barajas in the early hours of the morning," Medina would recall. "We were ordered to form up and remove our flying gear, including our leather jackets. All our equipment was shared out among their soldiers."

The next day, the aircrews were taken to the prison at Porlier. "I was tried and sentenced to death in Valencia on August 25, 1939," said Medina. "For seven months I waited for the sentence to be carried out. Seven months of watching comrades and friends pass on their way to their execution."

In the offices at ADAR, Calvo crosses his wrists in pantomime. "At 20, I am in handcuffs." He nods playfully at Guti, who is slightly stouter. "The reason he is healthy is he was eating," Calvo says, hands moving over an imaginary bowl, "while I…" He imitates working a pick at hard labor.

José Bravo got another war. When Hitler invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941, Bravo and other Spanish airmen living in Russia served as partisans until a chance encounter with a former Soviet boss put them back in fighters. The last airplane Bravo flew was a Bell P-39 Airacobra, in 1948.

In the mid-1950s, Spanish exiles began returning to their homeland, through a program of repatriation arranged by the International Red Cross. Bravo returned in 1960, and was promptly interrogated about Soviet military facilities (the cold war had made Franco an ally of the West) put under surveillance, and allowed to work only as a language professor and translator.

"When Franco died" in 1975, Gutiérrez says, "the government let us reclaim our rights." He is listed on the Spanish air force rolls as a retired comandante. Calvo and Bravo are retired air force colonels. Largely because of the efforts of these men to win recognition for their accomplishments, Spain now recognizes the ranks and pensions of all Republican veterans.

As for the victors, the German Condor Legion went home in May 1939, followed by the Italians. Germany would invade Poland in September, a month after cutting a non-aggression deal with Stalin. In the war that followed, Luftwaffe pilots would refine the tactics they had introduced in the skies over Spain.

But the "Stuka mentality"—the belief that one could dive-bomb and blitz the enemy into submission—proved a fatal delusion. Germany continued to rely on medium bombers, having used them successfully in Spain. The Germans had no armadas of long-range B-17s and Lancasters in the next world war, so there were no British Dresdens or Hamburgs. Ironically, the Condor Legion's Spanish victories helped sow the seeds of Hitler's ultimate defeat.

Longtime contributor Carl Posey writes from Alexandria, Virginia.