They Couldn’t Stop Amelia Earhart

The famous American’s attempt to fly around the world was nearly thwarted by British officialdom.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20/98/20986982-4164-4760-acf0-7546a79eb0c9/02b-d_dj2022_earhart_opener_live.jpg)

In the 1930s many territories on the Arabian coast were under the protection of the British, who held the exclusive right to grant visas and therefore controlled the airspace. Aviators flying to and from the Far East were directed to fly over Persia, not Arabia. Both KLM and Air France had to fly the northern route, while only the British-owned Imperial Airways was allowed to land at the two regular aerodromes on the Arabian side, Bahrain and Sharjah. Such was the British domination of the region that The Times dubbed the airspace over the Persian Gulf “the Suez Canal of the Air.”

Among the reasons advanced for banning aircraft from the Arabian side of the Gulf was its desolate terrain, inhospitable climate, and lack of facilities. Aircraft were almost unknown—and unwelcome. It was said there was a danger of injury or death at the hands of “wild tribesmen” if an aviator should need to make an emergency landing. There was some truth in these assertions, for the Arabia of the 1930s was a vastly different place from the oil-rich countries of today.

However, there was another agenda at play—a British desire to exclude their rivals from the region. The area was emerging from a traditional way of life into the harsh daylight of the oil age and, through a desire to protect their own interests, the British sought to keep other countries out. The policy went to the absurd lengths of banning private aviators and was challenged by assorted types of pilots, ranging from the eccentric Maurice Wilson (who planned to crash land on the slopes of Mount Everest and then ascend to the summit) to the secretive Lord Semphill, who was suspected of spying for the Japanese. Many of these pilots were swiftly discouraged.

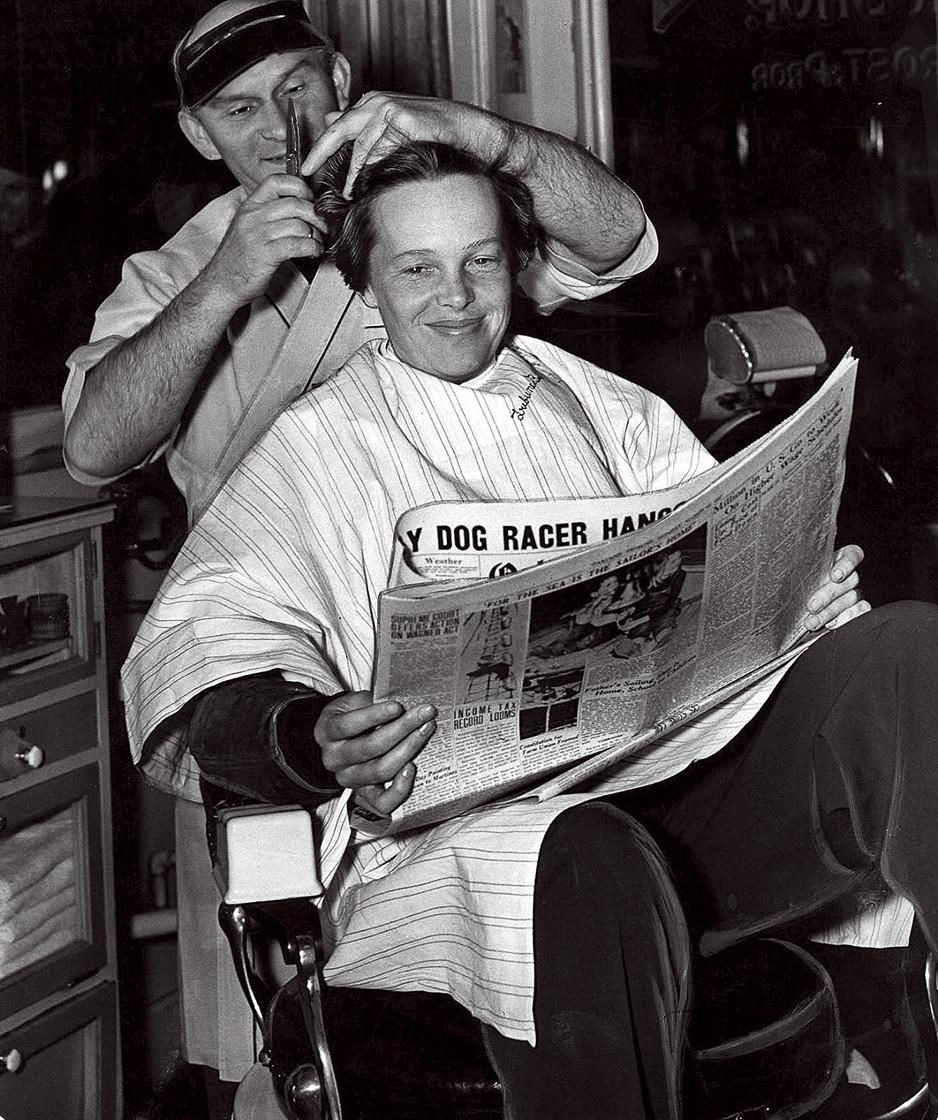

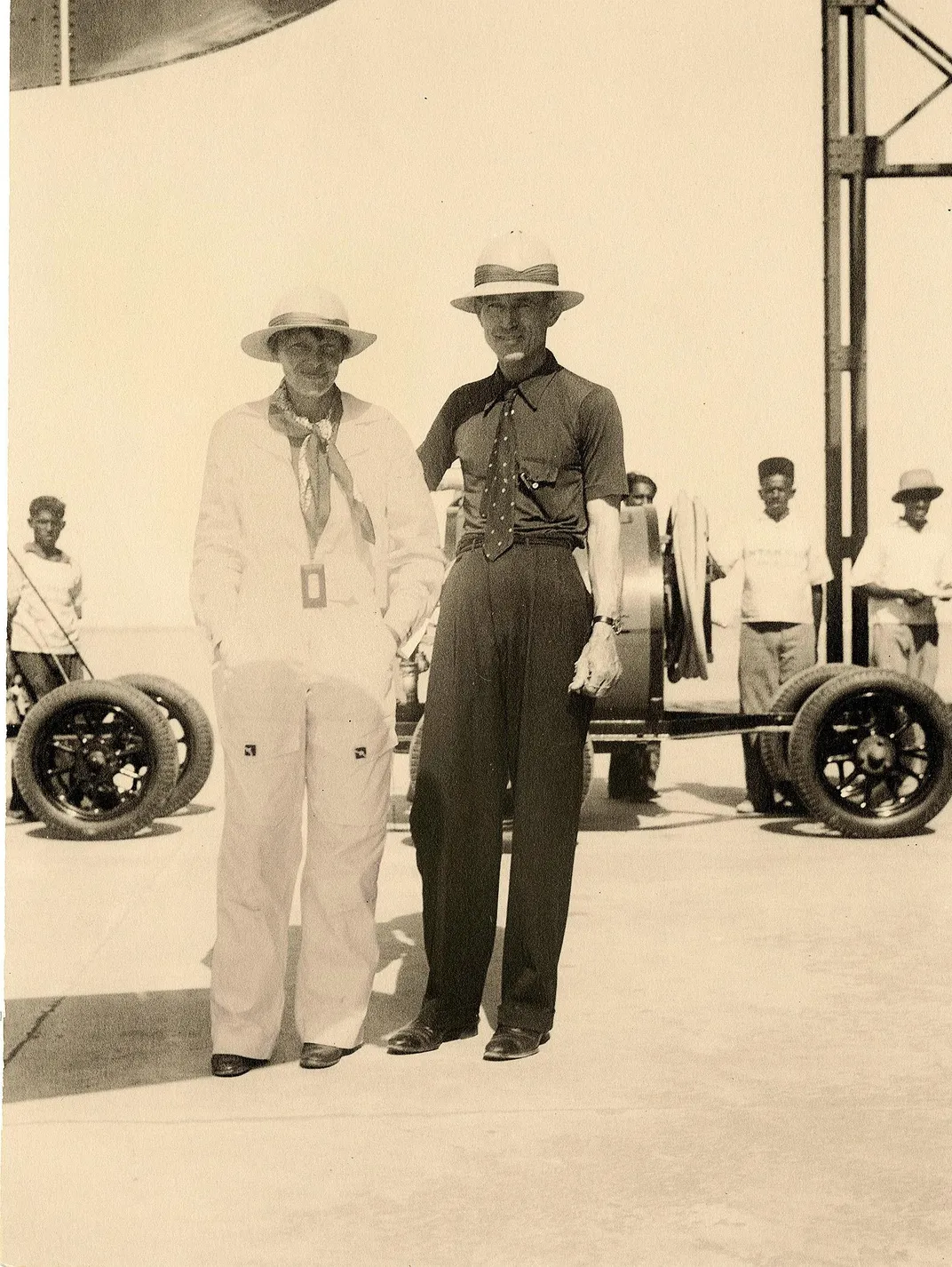

The American aviator Amelia Earhart was in a different league, and her request to cross the British strongholds became a matter of international diplomacy. By 1936 she had already made her name as a flier of great distinction, being the first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean and nonstop across the United States. She was now planning to fly around the world and, to this end, the U.S. Ambassador in London, Robert Bingham, wrote to Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden outlining Earhart’s plans. The flight would include a leg between Karachi and Aden. Since this would have involved flying over the Sultanate of Oman, permission had to be obtained for the flight.

The request met a frosty reception: Bingham was told that the Sultan was unlikely to give his permission for the flight, and that Oman was “desolate, inaccessible and entirely unsuitable for any emergency landings, should Miss Earhart, unfortunately, be forced to make one.” Miss Earhart didn’t let a little thing like British paranoia over their oil wealth stop her.

In the book Last Flight (published posthumously in 1937 by George Palmer Putnam, Earhart’s husband), Earhart’s diary entry notes: “Finally the authorities relented. They concluded, I believe, that my plane was capable of making the two thousand mile nonstop flight necessary to carry it from the Red Sea to India, without undue likelihood of forced landing on Arabia’s forbidden sands. The British were very friendly and cooperative about it. They gave permissions to land at Aden, and permission to fly thence to Karachi, possibly stopping first at Gwadar, 350 miles up the coast at the mouth of the Persian Gulf in Baluchistan close to the Persian border. It was stipulated that we were not to fly over Arabia itself but along the edge of the sea.”

As it happened, by the time she embarked on her journey in June 1937 with navigator Fred Noonan, she had reversed her route around the globe and flew eastward, using Aden as a checkpoint and flying nonstop from Assab in Eritrea to Karachi in India (as it was then). She followed the line of the south Arabian coast, but stayed over the sea. In the sky, far away from political complications, it was simply a matter of the pilots, their machine, and the flight: The Arabian Sea catching the first flecks of sunlight as the twin propellers of a Lockheed 10E Electra stirring the rising air, pulled the fuel-laden aircraft past “the razor-back ridges” of the southern coast of Arabia on its way to Karachi. With extra tanks on board, Earhart and Noonan were taking no chances of running out of fuel and landing on a hostile shore. And, to cover all eventualities, Earhart carried on board a letter written in Arabic assuring anyone who might approach her downed aircraft that she came in peace.

Thankfully, it never came to that. She arrived safely in Karachi after a record-breaking flight of 13 hours, 10 minutes. Despite being forced to fly over the sea, which greatly increased the danger, Earhart was remarkably generous toward the British officials who had tried to thwart her, describing them as “very friendly.” However, while it was generally believed that the Saudis had prevented her from flying over the land, it is now clear that it was the British who had stopped her from flying over Oman, since they—not the Saudis—effectively controlled the airspace. In any case, Earhart never achieved her ambition of flying around the globe. Her aircraft famously disappeared in the Pacific two weeks later, and her fate remains one of the great unsolved mysteries of 20th century aviation.

The British policy was ultimately doomed to failure. The oil boom brought many foreigners to the region: managers, geologists, drillers, office clerks, and more. World War II intervened and the world that emerged afterward was a different place. On December 7, 1944, 52 nations signed the Chicago Convention which, among other things, allowed airplanes from different countries to pass over the Arabian peninsula or refuel on the Arabian side of the Gulf. As a result, the British government obtained the agreement of local sheikhs to conform to the Chicago code so that airlines such as TWA and Air France could fly over or land in their territories.

The empire of the skies might have been over, but the name of Amelia Earhart lived on.