The Thrill of Flying the World’s Smallest Jet

Jim Bede and the 1975 BD-5 Jet Team

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c4/6e/c46e2b89-7bc0-4a4f-934b-175d42db4074/11g_aug14_flightlineseries_live.jpg)

Last summer while I watched Justin Lewis perform at an airshow in his polished silver BD-5J, that old feeling came back. I longed to strap into a BD-5 jet again. I wanted to dive it along the show line, pull up vertical, gyrate through a Wild Turkey, drift backward into a tail slide, bop the gear up and down, then zoom past the airshow crowd the way we used to in 1975, when I was the third pilot of the BD-5 Jet Team.

Sleek as a bullet, efficient as a sailplane, sexy as a little Reno racer, the BD-5 was the key piece in Jim Bede’s 1970s dream of affordable, fun flying for the masses. Bede had already hit a home run, selling more than 800 kits for his boxy, practical, build-it-yourself BD-4. But orders for the BD-5 soared into the thousands.

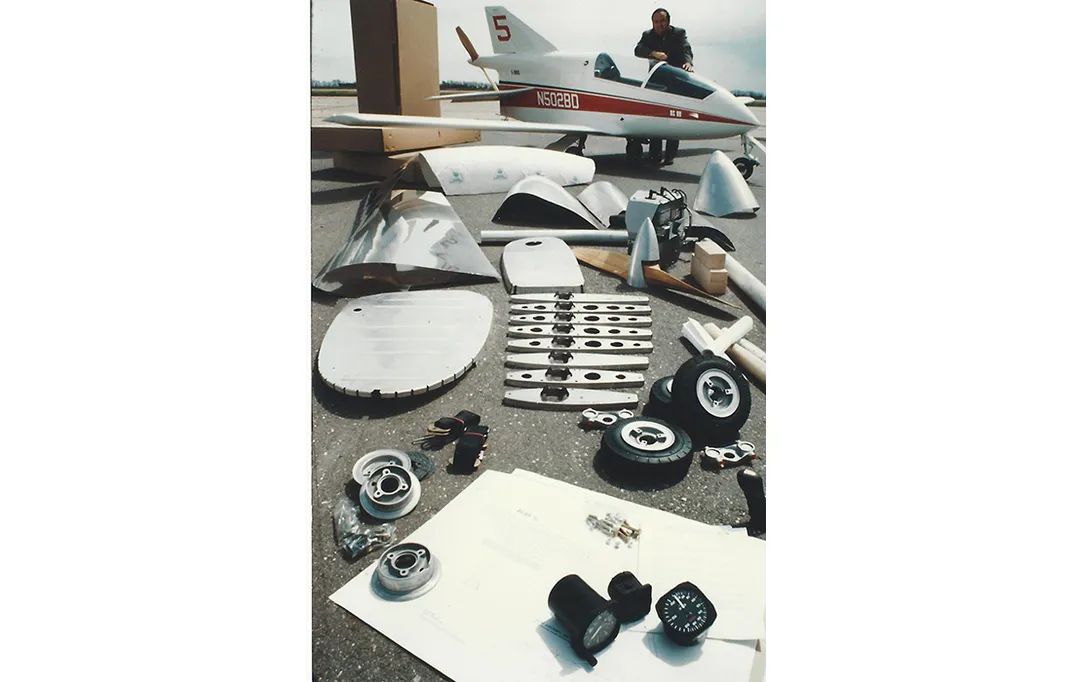

The airplane whispered fantasy and adventure. Nothing about it said wife and kids. Built at home, slipped on at the airport, it was a single-seat, man-size toy. With a fuselage not much bigger than a motorcycle (empty weight: about 450 pounds), it earned a Guinness record as the world’s smallest jet. Its wings and tail could be removed for storage in a garage instead of an expensive-to-rent hangar. The public panted for it. Even before the airplane flew or the engine ran, people sent deposits hoping for kits to build or places in line for the production model.

At the Experimental Aircraft Association’s AirVenture in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, last July, Lewis told me that seeing BD-5 jets in the 1980s and 1990s inspired him to fly. He also talked about building his own Flight Line model with Skeeter and Richard Karnes at BD-Micro Technologies in Siletz, Oregon, one of the places where amateur builders can get help putting a BD-5 together. Because the Federal Aviation Administration classifies the BD-5 as “experimental,” the Karneses, who bought parts from one of the original dealers, are able to make any modifications they like. Lewis described the changes. “It has beefed-up wings, a more powerful engine, and a five-inch stretch to the fuselage. It still flies like a dream,” he said with a grin. For my part, I told him stories from when I was left wingman on the demonstration team with fellow airshow pilots Bob Bishop and Corkey Fornof. Back then the jet was relatively new, full of surprises, and watched enviously by crowds of people who wanted one of their own.

Bede Aircraft had already begun its historic tail slide when I flew my first airshow with the team in May 1975, but I did not know that. Marketing was so far ahead of development that incomplete kits were being shipped to customers; necessary parts simply hadn’t been made. More ruinous, there was no off-the-shelf, airworthy, two-cycle piston engine for the -5, and it was the low-cost piston engine model that homebuilders wanted, not the $20,000 jet. No airplane had ever used such an engine, and in trying to develop one, Bede’s team of engineers and the snowmobile engine manufacturers they were working with seemed to be running in quicksand.

Still, everyone I worked with was under the airplane’s spell. Bede Aircraft in Newton, Kansas, was a magnet for pilots, mechanics, and engineers excited about homebuilding airplanes. Fornof, who led the jet team and had flown airshows in the P-51 Mustang and F8F Bearcat, acquired a Bede dealership to sell kits and later, he hoped, production airplanes. Bishop, who had become famous for his airshow performances in the Bellanca Super Viking, flew right wing and had put a deposit on one of the production models. Dan Cooney, destined to solve mysteries in the drive train that linked the mid-fuselage engine to the rear-facing propeller, showed up in Newton with his Cessna 172 ready to camp out until they found him a job. Engineer Al Thompson, who worked out how to build the unique mechanical landing gear, arrived from Boeing. Now-famous aircraft designer Burt Rutan left a civilian job at Edwards Air Force Base to become Bede’s flight test director.

“This was the only real job in the homebuilt industry,” says Rutan. “There wasn’t any place else where I could work a day job that was something I did for fun at night.” Rutan arrived in Newton with his own, nearly finished design, the VariViggen. While he was at Bede, from 1972 to 1974, he improved the BD-5 prop version, converted the propeller -5 to the jet -5, and developed Bede’s concept of a trainer called Truck-a-Plane: a BD-5 airframe suspended from a trapeze in front of a pickup truck. It offered a simple, ingenious way to practice the critical first and last 20 seconds of flight, close to the ground. Since the BD controls were extremely sensitive and the airplane sat as low to the ground as a glider, takeoff and landing were tricky for inexperienced pilots.

Rutan’s other contribution was to make Les Berven the BD-5’s test pilot. Rutan and Berven worked together at Edwards and flew the airplanes in the base’s aero club. “Even though Les was a flight test engineer like me, he was bonkers about flying,” Rutan says. “He was a stick-and-rudder guy. I knew Les would be a better pilot for a BD-5 than any military test pilot stepping down from Phantoms or F-15s.” Bishop called Berven our cowboy test pilot. He was serious about his test flying, but everything else was fodder for his wacky humor, like the rivet gun recording he hooked to his radio, which in our cockpits sounded like a machine gun shooting us down.

Even people in the office felt the little jet’s magic pull. Carol Hall worked with her husband John, who was marketing vice president. “It was almost a cult,” she says. “You belonged to something. You worked for a cause. If you didn’t get paid, well, you could live on creativity. John and I worked in the car driving to Newton from Wichita with boxes of folders and files, answering letters. We took the kids there in our Volkswagen camper on weekends. We were all working to provide this wonderful airplane to all these customers who put money down. Those $200 checks that came in just to hold a spot, they just poured in. You couldn’t count them fast enough.” John Hall was critical to Bede’s business in two ways: He directed the BD-5’s extensive publicity campaign, and he lovingly drew the BD-5 building plans, famous for their meticulously planned build sequence.

I showed up in Newton because Bishop and Fornof said there might be a job for a wingman if I had time to hang out. I had just finished a year and a half in Canada as a pilot on the four-Pitts Carling Aerobatic Team when Bishop called me to replace their number three pilot, Ed Mahler. The little jet is slippery and sensitive, and the six-foot-four Mahler found it awkward in formation. So he became their solo pilot until the day his jet sucked in contaminated fuel at Corpus Christi and flamed out, and the aircraft went down on a sandy patch near the airport. Mahler peeled off the fuselage and escaped with a broken palate. Fornof and Bishop flew the rest of their 1974 20-show season without him. (Mahler went back to flying his Parsons-Jocelyn biplane; in 1977, he crashed it in a show and died.) Bishop had seen a video of me flying in the Carling Team, so he figured I could do the job, and he thought a woman on the team would increase its market appeal for a corporate sponsorship. Fornof was skeptical; he didn’t know any professional women formation aerobatic pilots, because there were none—except me. I’d led a team for acclaimed airshow pilot Jim Holland from 1971 to 1973, then flew the number four, or slot, position on the Carling Aerobatic Team. (The slot flies right behind the leader in a diamond formation.) When I showed up in Kansas that May, Fornof said I could try out, but that I would probably not be ready to perform with the team before Oshkosh, at the end of July.

But when we flew together, I felt at home in the jet and comfortable with their formation routine, and Fornof changed his mind. In the journal I kept in 1975, I noted what he said: “If a man had flown that well, I wouldn’t have been quite so surprised.” We both laughed. It was the sort of thing people said in the 1970s, but I didn’t let it offend me, and I never let it stop me. Our new team flew our first show 10 days later there in Newton for Bede customers and employees, and the rest of the summer the three of us had a wonderful time flying together.

Our job on the jet team was to keep the BD-5 in front of the public. At the start, Bede invited us all to his office for a welcoming toast. I looked around. Bookshelves held thousands of National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics manufacturing reports dating from the 1920s and 1930s onward, some printed on cheap, fragile paper from World War II. “Have you read all these?” I asked.

“I live on them,” Bede said, reaching for the one titled The Hinge Moment of Control Surfaces. “Here is one of the secrets to the BD-5’s beautiful flying characteristics.”

Handmade models on a cabinet across from his big desk gleamed under a spotlight. With Bede’s drawing on quadrille paper as a guide, Paul Griffin designed them. In 1964, after reading a Mechanix Illustrated article about the BD-1, Griffin joined Bede Aviation (which became Bede Aircraft) as an illustrator. His models gave life to Bede’s ideas. At the flight test center, he would work a full day on the BD-5 project, then stay late sanding a model of the next Bede concept.

Because of the slow and partial shipments of kits, the initial intoxication over the propeller version of the BD-5 needed reinforcement. We all got a chance to fly the prop plane too. In fact, right after the Newton show, we took one to the big airshow in Reading, Pennsylvania, because our jets had been shipped to Edwards for testing and research by the Air Force. With Bishop’s supervision, the U.S. Navy had used the jet to mimic a cruise missile in an effort to convince the Carter administration that a cruise missile was a better cold war weapon than the B-1 bomber. Now it was the Air Force’s turn. It was fun to imagine this seemingly frivolous little machine having a secret life as a military weapon, or as a spy’s tool. Hollywood also saw its spyplane potential, casting it in the 1983 James Bond movie Octopussy, with Fornof at the controls as Roger Moore’s double.

At our next jet show, in Mojave, California, I made five practice flights, and each time I rolled or dived, my engine made harsh sucking noises and flamed out. No formation flying for me that weekend. Instead, the show was memorable for a different kind of experience. I allowed one curious fan to sit in my jet, and as I was telling him that its range was 550 nautical miles, another man interrupted. “You can cut that by 90 percent. You can cut anything Jim Bede says by 90 percent,” he said. “Jim Bede is all talk, and anybody who works for Jim Bede is a liar!”

Although I’m embarrassed to admit it today, I thought he was a crank slandering a guy I believed in, and I told him to get lost. Recently I asked Bede about that tough time for him and the company. “Out of about 10,000 customers I got some very mean hate mail from about 100 people,” he says. “Some people thought that if they really put pressure on me and made me feel bad by writing to the magazines and the government that I would solve the problem.”

But making Bede feel worse didn’t solve the engine problem. “When you are running as fast as you can and somebody says ‘There’s a flaming torch behind you, run faster!’ you go ‘This is as fast as I can go here,’ ” he says today. “So many good people like Paul Griffin and John Hall put all their effort into it.”

And enthusiasm for the BD-5 was so broad, way beyond the homebuilt market, that Bede believed the way forward was to manufacture a production airplane. This required getting the airplane certified by the FAA, a tedious process involving unimaginably vast amounts of time, money, and red tape. In 1972, right after Curtis Pitts got his aerobatic Pitts biplane certified, he told me, “If I had ever known how difficult and expensive it was going to be, I never would have done it. It cost more than a million dollars.”

Bede sank his house, his personal accounts, everything he and his family owned into the company to try to save it, and somehow remained optimistic about future deliveries.

Our jets spent a lot of time at Edwards in the summer of ’75, and the next time we climbed into them was to taxi out for the Fourth of July show in Lancaster, Texas, near Dallas. I had gone six weeks with no three-ship practice. Formation aerobatics is all about timing and practice. On the Carling Team, we had a big budget and plenty of control, so our training included six weeks of winter practice. The Bede Jet Team was on a very tight budget, but after the Lancaster experience, we never did another show without practice.

The Fourth of July weekend in Texas was so hot that 40 people in the crowd fainted, and the air was as rough as stones. We dived in for our first loop and I cranked my elevator trim to the full nose-down position to make my controls so heavy that I would not chase the bumps and have the jet’s nose bounce up and down like a truck with bad springs. Don’t move the stick, I told myself as the plane rode over the bumps. In an aircraft as light on the controls as the BD-5, it is easy to overreact. It was hard work, but that’s the fun of formation flying.

Another part of the fun of being on the team was traveling to shows in Bede’s DC-3, which also transported our jets. For four years I had traveled to shows in a Pitts with all my belongings stuffed in a tiny back hatch the size of bread box, so I was giddy over all the space and freedom the DC-3 gave us. We three took turns: up front as the copilot, or in the back on a bench. It was a party back there, with buckets of fried chicken and magazines we read aloud to each other. The jet fuselages were turn-buckled to the floor with the wings and horizontal stabilizers tied down under them, wrapped in blue sleeping bags. It was especially fun arriving together for my first airshow at the yearly Oshkosh convention.

We performed both solo and team flights, and when not flying, we manned the Bede booth. By the second day I was hoarse from raving about the BD-5 and shouting hello to what seemed like everyone I had ever met in aviation. Although we performed our formation flight in the rain, we flew the routine with rhythm and finesse, and I remember feeling great; but I also remember that I got a slow start on takeoff. From the left wing I saw Corkey’s mouth move, then his jet crept away before I realized I was on the wrong radio frequency.

What I was really looking forward to was my solo flight; I had practiced a surprise. Our jets had been home with us for a week, so I’d had a chance to experiment. The Bede jet could do things that other jets can’t: snap rolls, tail slides, and our signature level pass, called Now You See Them, Now You Don’t, with the landing gear popping in and out as we moved the mechanical landing gear lever forward and back. My surprise was to do an inside/outside figure eight, the first and maybe only negative 3-G maneuver done in a Bede jet at an airshow. Before I tried it back in Newton, I checked with Berven and the company mechanics and engineers. I stayed within the airplane’s G and oil pressure limits, so I expected no problems. The airplane sailed through the inverted portion of the eight as if it was built for negative Gs. It delighted me, but not Bishop. “The nickel cadmium batteries are right under your legs,” he said after I flew. “The caps on those batteries are only certified for three negative Gs. If that stuff got loose on you, you would have been in very bad shape. You could have lost the use of your legs.” I didn’t perform another inside/outside figure eight.

Bishop was not just a talented wingman, but also the one who gave us reality checks. He knew the airplane better than anybody else. Not long after Oshkosh, something happened that made him say our days as a show team were numbered. For a long time, the engineers and mechanics had been working to perfect the “conformity model” BD-5 so the airplane could meet FAA certification requirements. We all thought the BD-5 production airplane was just around the corner. That’s what we told people we met on the show circuit, and deposits rolled in from customers wanting places held in line for them. But Bishop sensed that the delays were not the ordinary hurdles that every airplane has to overcome during development, so he introduced Bede to Rod Absher, the aircraft production expert who saved Bellanca Aircraft 800 man-hours per airplane when the company set up its new production line. After a couple months at Bede’s, Absher took Bishop aside and said the company was a long way from starting production.

In September, I left Bede’s to fly solo shows in my new Pitts S-2A and to set up an aerobatic school at Art Scholl Aviation in California. Bishop and Fornof left a couple months later to build their own jets and find other sponsors. They flew together for a long time—first as the Acrojets, then as the sponsored Sonic Jets. Then they split; Fornof headed for his movie stunt flying career, and Bishop formed the long-running Coors Silver Bullet Team. Bishop did some BD-5 test flying for Ames Industrial Corporation, which had built the original BD-5 jet engine under license from the French engine builder Microturbo (then Sermel). The company had purchased 20 BD-5 kits, and Bishop negotiated a good deal for 19 sets of parts. He has since used the kits to build many of the jets he now owns and flies under contract for the military as the Small Manned Aerial Radar Target, or SMART-1. Justin Lewis, an Air National Guard pilot as well as an airshow performer in the BD-5FLS, sometimes flies missions for Bishop.

In 1979, Jim Bede lost his company, his savings, and his home to bankruptcy. Customers lost their money too. Bede didn’t intend to cause harm; he just didn’t see how bad things had become.

Bede has written a book about his experience: The BD-5 Story. It’s sold by the company he formed with his two sons in 1998, Bedecorp, which also sells kits for four models, including the BD-4. But not the BD-5. Bede calls the BD-5 a dream. It was a dream I got to live in the summer of 1975.