The Thunderjet Had the Body of a Fighter and a Bomber’s Soul

The F-84 earned its reputation for ruggedness.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Thunderjets-631.jpg)

A novelist who savors irony could turn the story into a bestseller: A gravely wounded Russian military pilot emigrates to the United States, founds an aircraft company, and hires a brilliant Russian engineer who becomes the firm’s chief designer and creates an array of warplanes for use against...the Russians.

The novel would be based on fact, namely the life of Alexander P. de Seversky, a wealthy Russian who lost a leg as a naval pilot in World War I and in 1918 emigrated to the United States, where he developed a synchronized, automatic bombsight for the Sperry Gyroscope Company. When the U.S. government bought the patent rights to the bombsight for $50,000, Seversky settled in New York and, in 1922, used the money to establish the Seversky Aero Corporation on Long Island. (Seversky Aero later became Seversky Aircraft Corporation.) But by 1939 the firm had lost $550,000, and in a twist of fate the board of directors forced Seversky out and eradicated his name from the company, which they renamed the Republic Aviation Corporation.

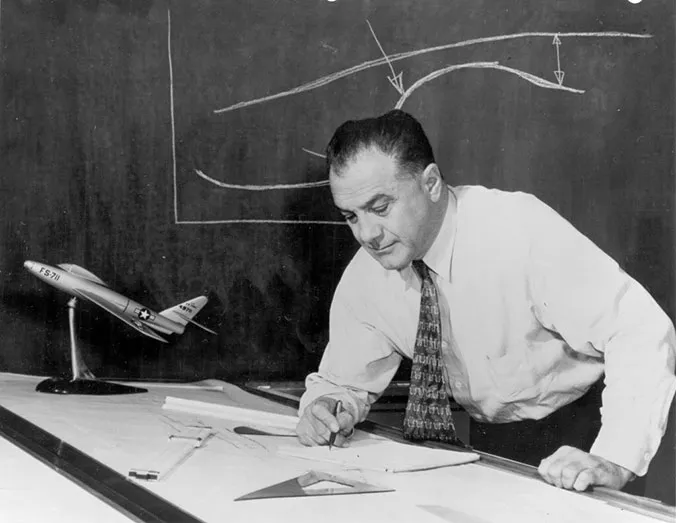

Among de Seversky’s stable of designers was a young Alexander Kartveli—thought by many to have been in the same league as the legendary Clarence L. “Kelly” Johnson, the head of Lockheed’s Skunk Works and the mastermind behind the U-2 and SR-71 reconnaissance airplanes. Kartveli, generally known for his rugged designs, actually had an artist’s eye. “He liked streamlining—he wanted his designs to be beautiful,” says Joshua Stoff, curator of the Cradle of Aviation Museum on Long Island, New York. In 1939, Kartveli drew an airplane designated the XP-47 that showed his fondness for clean lines. He designed it to be powered by the latest Allison water-cooled engine, which, in the late 1930s, enticed engineers with its inline arrangement of cylinders because it presented to the oncoming air a much smaller area than the big radial engines of the time. But after early European combat reports showed that lightweight fighters (such as the Royal Air Force Supermarine Spitfires and Hawker Hurricanes in action at the time) were too easily eliminated from the battle by gunfire, the U.S. Army Air Corps asked for a much heavier fighter–bomber escort in a single airframe.

“The [XP-47] morphed into the P-47 around a big radial engine and its supercharger,” says Stoff. “The Air Corps requested a big, heavy airplane to carry a lot of ordnance, but it was a much bigger, heavier plane than [Kartveli] would have liked.”

But in the end, Kartveli was a pragmatist—if the Air Corps wanted a juggernaut, that’s what it would get. The potential of the powerful new Pratt & Whitney R-2800 Double Wasp engine couldn’t be denied—the engine ruined the XP-47’s lines, but resulted in the barrel-chested, multi-role P-47 Thunderbolt, one of the best ground attack aircraft in World War II.

As early as 1944, Republic began work on designs for a jet fighter, writes Stoff in Thunder Factory, a history of Republic Aviation Corporation. Following the Luftwaffe’s introduction of the Messerschmitt Me 262 in mid-1944, the U.S. Army Air Forces “asked Republic to redesign the P-47 around an axial-flow turbojet,” says Stoff. “The engine would have been installed in the roomy center fuselage, exhausting under the tail.” After preliminary sketches showed the idea to be impractical, Kartveli scrapped the concept and came up with an all-new design, the P-84. Two years later, the XP-84 made its first flight.

At this point, Republic began experiencing financial troubles, and by October 1946 the company had cash to continue operations for only three weeks. “Republic pleaded with the U.S. Army Air Forces to begin payments on the P-84 contract,” writes Stoff, “although the first production aircraft would not be delivered for another eight months.” The Air Forces advanced payment, and that, combined with a $6 million tax refund, allowed the company—and the now-redesignated F-84 Thunderjet—to survive.

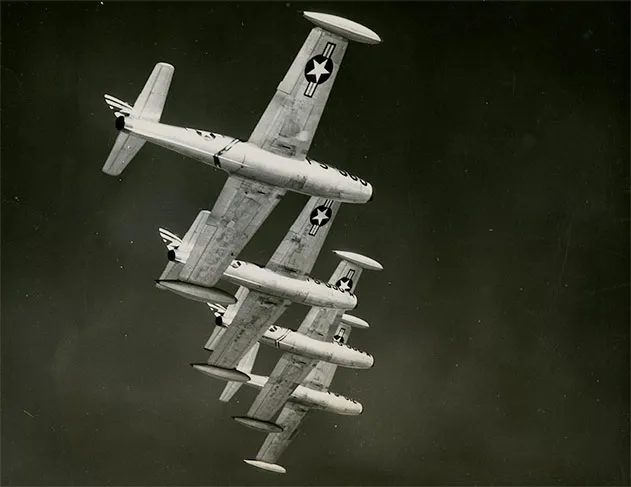

In December 1950, the 27th Fighter-Escort Wing became the first Thunderjet unit in Korea, flying F-84Es. Originally meant to escort B-29s on bombing runs, the F-84s were no match for lightning-quick MiG-15s in the Korean War. After ceding air-to-air combat to the North American F-86 Sabre, the Thunderjet built an honorable record pounding North Korean positions.

Republic F-84s flew 86,408 missions, and were the Air Force’s primary strike aircraft. They were credited with destroying or damaging 105 MiG-15s; 173 Thunderjets were lost or damaged in combat.

The Thunderjet’s performance in North Korea ensured that Republic’s reputation for ruggedness, enshrined in the Thunderbolt, continued into the Jet Age. Besides creating an aircraft that would satisfy basic requirements and hang tough under fire, Kartveli’s team paid attention to subsystems and the demands of field work, which would come to be appreciated by the shivering wrench turners on the Taegu Air Base flightline.

“Republic made a hell of an airplane. They knew what to do for the people who flew them and the people who worked on them, and with what tools,” says Douglas Danforth, who was an F-84 crew chief with the 27th Fighter-Escort Wing during the Korean War. “You could change an engine on an F-84 in under a half-hour and have the aircraft ready to fly.” Danforth also worked on the F-86 Sabre and found that legendary fighter much more difficult to maintain. “Republic had it all over the F-86 as far as maintainability. The F-86 was a royal pain in the ass.” A well-thought-out system of engine mounts, quick-disconnect couplings, and rolling stands made the F-84 a mechanic’s friend.

Guy Razzeto flew with the 27th. He found the F-84 lived up to its Republic reputation for survivability. “It was very effective,” he says. “We dropped napalm and did air-to-ground with eight .50-caliber guns. A lot of guys got hit and it pretty much flew on. I saw a guy get hit in the wing with a good-size [round]—I guess it was a 37-millimeter—and a booster pump in one of the fuel cells was hanging out by three wires. You could stand up in the hole.”

“For its time, it was a capable jet aircraft,” says Salvatore Stassi, also with the 27th Squadron, who had previously worked on the F-82 Twin Mustang. “It was built like a tank. The pilots liked it. It did go into air-to-air combat with MiGs...and the airplanes I crewed always came back. In those days we had no hangars [at Taegu], so we were out in the elements. And working on the F-84 was definitely different compared to a prop engine. The maintenance was less with an F-84 than an F-82—the F-82 had a lot of hydraulic problems.”

But for some, the inevitable comparison to the ruggedness of the P-47 Thunderbolt somewhat overstated the F-84’s status. Jacob Kratt, a 27th Squadron pilot whose career extended from propeller-driven fighters to the McDonnell F-4 Phantom and Convair F-106, found the F-84 to be dependable and capable, but somewhat unremarkable. “I didn’t think it was all that superior to the F-80 or the jets the Navy flew,” he says. “I flew the P-47 and the F-84, and the P-47 was a lot more rugged than the F-84,” he says. “But it held its own with any other jets that were flown in Korea. But when the jets came along, I preferred the jets—a lot more speed, altitude, climb rates...it was a much more powerful machine.”

Razzeto, who flew the F-84E, knew his upgraded jet came at the expense of hard lessons. “The first F-84s used the same main wing spar [design] as the P-47. Some of the early F-84s—like the D model—would fail if you pulled too many Gs,” he says. “But the E model -84 had a beefed-up main [wing] spar, so it was really rugged.”

The G model, the first production fighter that could be refueled in flight, participated in every major air operation in the final two years of the Korean War, says Stoff, including the 1952 dam raids that cut all electrical power to North Korea.

With a cease-fire on the Korean peninsula in 1953, F-84 production turned exclusively to the swept-wing F-84F Thunderstreak, the only Air Force fighter to trade straight wings for swept ones. (The Navy followed the same path with the Grumman F9F Panther, which, by sweeping its wings, Grumman turned into the F9F Cougar.) The F-84F was essentially a new design, but Congressional funding restrictions argued for retaining the -84 designation to avoid the appearance that the Air Force was buying a completely new jet. The F-84F led to the RF-84F Thunderflash, a high-speed reconnaissance jet that flew missions in Vietnam.

“The F-84F was kind of a different airplane,” Kratt says. “It was faster, and it had no limitations. You could take it up to 40,000 or 44,000 feet, point the nose down, and go supersonic. You couldn’t do that in a straight-wing [F-84]—the E or G [models] would come apart.”

But for supporting ground forces—in what was becoming a Republic hallmark—newer wasn’t necessarily going to be better. “As a gun platform, the E and G were much more stable than the F,” says Kratt. “The F was more susceptible to yawing—it wasn’t rock-stable like the straight-wing was. You’d shoot good scores, but not as good as a straight-wing.” Kratt likened the earlier Thunderjets to his first experience with a Republic aircraft. “I was in Europe when I got into the P-47, and after the war we had [gunnery] ranges so we could shoot air-to-ground,” he says. “They were very similar—both were very stable airplanes.”

After Korea, the F-84G took a turn in 1953 as the first aircraft of the 3600th Air Demonstration Squadron, better known as the Thunderbirds. The team switched to F-84Fs in 1955.

As the cold war intensified, F-84s would serve as testbeds for some unusual projects, including a radical solution to replace the runway with a “zero-length” launch system. The system used a booster rocket from a Matador cruise missile to fling an EF-84G from a platform into the air at a shallow angle. That system enabled the aircraft to be launched in forward wooded areas, so close air support could be made faster and more accurate. But the technique quickly proved too dangerous for the pilots so the idea was dropped.

Instead, the G model was adapted for another purpose. Taking advantage of the Thunderjet’s stability as a weapons delivery platform, the Air Force retrofitted the fighter-bombers with a low-altitude bombing system and nuclear bombs for missions against targets in the Soviet Union.

Guy Razzeto was one of the pilots trained to fly the nuclear strike mission. After the Korean War, Razzeto says, “we trained to carry ‘A’ bombs, and went to inflight refueling [in the F-84G]. We could go anywhere in the world.” Beginning in August 1953, the Strategic Air Command deployed nuclear-capable F-84s to Europe. By 1955, more than 550 fighters were equipped for the mission. These were eventually replaced by North American F-100s.

In 1949, the imaginative Kartveli turned the Thunderstreak into the XF-91 Thunderceptor by supplementing its jet engine with a cluster of rockets that were supposed to provide extra thrust for the final burst of speed during the intercept. The airplane’s most notable feature was its wings, which were much wider at their tips than at their roots, giving them increased lift but a very odd appearance. And like other fighter-interceptor designs of the time, the XF-91 had a too-brief total flight time—only 25 minutes for the Thunderceptor—making it virtually useless for U.S. border defense. It eventually lost the competition to defend the country to the F-86D Sabre, which had a far longer range; Northrop’s large, straight-winged F-89 Scorpion; Convair’s F-102 Delta Dagger and F-106 Delta Dart; and Lockheed’s F-94 Starfire, which carried a ring of air-to-air missiles in its nose. Two XF-91s were built and flight-tested 192 times over the course of five years, then retired.

Then there was the XF-84H, which served as a test platform for the Navy: By using a turbine engine to drive a massive 12-foot propeller, the XF-84H could lift off from fields as short as an aircraft carrier deck. Only two were built. While the experimental aircraft set an unbroken speed record for a propeller-driven aircraft—670 mph—its blades delivered loud, and nausea-inducing sound waves while on the ground, and the Navy dropped the idea.

Despite the dead ends, the trials did prove one thing: the Thunderjet’s versatility. That was one of the traits that made it attractive to America’s cold war allies and neutrals, including Josip Tito’s breakaway regime in Yugoslavia, which bought F-84Gs. Of the 7,524 Thunderjets that rolled out of the factory in Farmingdale, Long Island, hundreds were bought and flown by the air forces of other countries: Belgium, Denmark, France, Greece, Iran, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, the Republic of China (on Taiwan), Thailand, and Turkey. The last in operation, three RF-84Fs in the Greek air force, were retired in 1991.

Air Force pilots, like Razzeto, provided the schoolhouse for friendly countries and their new Thunderjets. “We went to Formosa to train [the Chinese] to fly the F-84G,” he says. “We had already converted to the F model—the swept-wing version—and they got F-84Gs through the [Military Assistance Program].”

Even with its versatility and hard-won respect firmly a part of aviation legend, it was clear to Kartveli that a successor to the F-84 was needed, so in 1951, he turned his attention to the F-105 Thunderchief, a high-speed, low-altitude nuclear bomber that drew some inspiration from the RF-84F Thunderflash—in particular its distinctive wing-root intakes. The Thunderchief would carry on the Thunderjet’s ground-pounding tradition in Vietnam.

Although the F-105 was a success, Republic was hemorrhaging money by 1965, forcing a merger with Fairchild-Hiller. That led to the closing of the plant in Farmingdale in 1988. In 1972 Fairchild-Republic met an Air Force requirement for a close air support fighter-bomber by producing the A-10 “Warthog”—dubbed the Thunderbolt II to celebrate its heritage.

“Republic proved its versatility going from the Thunderjets to the F-105, which was basically one of the fastest aircraft close to the deck,” says Ken Neubeck, a former A-10 engineer who has written books on the F-84 and other Republic aircraft. He notes that the A-10’s roots go right back to the P-47, which was also a ground attack aircraft.

Neubeck and a small group of fellow Republic alumni have formed the Long Island Republic Airport Historical Society, which meets in Farmingdale on the third Saturday of every month to reminisce about their place in U.S. aviation history, collect information about their former employer, maintain contact with friends and relatives of former employees, and help researchers who are studying Republic and its place in the evolution of U.S. military aircraft.

Nearby, the American Airpower Museum displays an F-84, as well as a flyable P-47D and an F-105. The museum’s directors, mindful of the area’s important history, have seen to it that special attention is given to the two aircraft that bookended the designs of a modest Russian genius.

William E. Burrows is an Air & Space contributing editor. A retired New York University journalism professor, he is the author of This New Ocean: The Story of the First Space Age (Modern Library, 1999).