Ticket to Ride

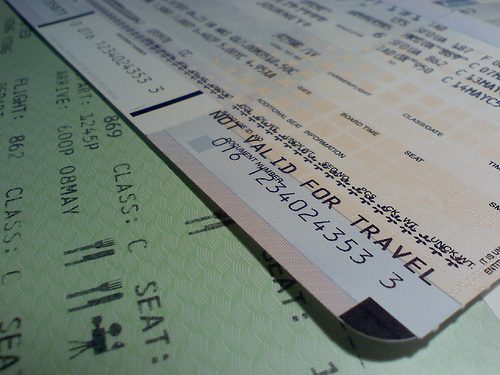

The next time you book a flight online and print your own airline ticket, give a moment of thanks to IBM and American Airlines. If it weren’t for those two companies, we’d still be carving our tickets out of stone tablets.Commercial travel was so simple back in the 1920s. One airmail plane, one ava…

The next time you book a flight online and print your own airline ticket, give a moment of thanks to IBM and American Airlines. If it weren’t for those two companies, we’d still be carving our tickets out of stone tablets.

Commercial travel was so simple back in the 1920s. One airmail plane, one available passenger seat. Things got a lot more complicated when multi-passenger aircraft were introduced.

Through the 1930s, American Airlines used a “request and reply” system: A travel agent would contact an American Airlines sales agent at the trip’s initial departure point and request a seat; the sales agent would contact inventory control to confirm the seat, if available, and reply to the travel agent (by telephone or teletype). The travel agent would then call the passenger. Once payment had been made, the travel agent would give the passenger’s information to the ticket agent, who would then pass it along to inventory control.

The system was manageable—if cumbersome—but with the advent of World War II, demand for air travel began to exceed available seats. Display boards were installed in reservation offices; by glancing at the board, a ticket agent could quickly see if there was available space on a particular flight. As passenger volume and scheduled flights grew, reservation offices—and availability boards—became larger and larger.

In a history of Sabre (by Duncan Copeland, Richard Mason, and James McKenney), the authors note that to accommodate the increased traffic, reservation boards grew to about 20 feet square. In their history, the authors include a description of American Airlines’ Chicago office:

A large cross-hatched board dominates one wall, its spaces filled with cryptic notes. At rows of desks sit busy men and women who continually glance from thick reference books to the wall display while continuously talking on the telephone and filling out cards. One man sitting in the back of the room is using field glasses to examine a change that has just been made high on the display board. Clerks and messengers carrying cards and sheets of paper hurry from files to automatic machines. The chatter of teletype and sound of card sorting equipment fills the air.

All of that changed in 1953, when IBM salesman Blair Smith boarded an American Airlines flight from Los Angles to New York. His seatmate was another Smith—C.R. Smith, president of American Airlines. But Blair didn’t know his seatmate’s identity. As he explained in a 1980 oral history conducted at the Charles Babbage Institute, “It took ten hours to get to New York because of intermediate fuel stops. So when you’re going to be sitting next to someone that long, you kind of look them over. I looked over this guy and I noticed his white shirt should have been changed a couple of days ago. He also needed a shave. I immediately decided that he was probably an unsuccessful traveling salesman returning from a bad trip, and just dismissed him…. Pretty soon we got to talking, and this man turned out to be a master conversationalist. Within thirty minutes he knew my life story, and I only knew his name was Smith and his shirt was dirty and he needed a shave…. I learned later that he would be sitting in his office in New York and he’d suddenly wonder how things were getting along in L.A. He would tell his secretary, ‘I’m going to L.A.’ He would go to the airport, just walk on a plane, and fly out without a shaving kit, pajamas or anything. Then he would take a look around and catch another plane back.”

C.R. Smith asked Blair what IBM could do to improve the airlines’ reservation system, and the rest is history. IBM programmers built a computerized transaction-processing system for American Airlines known as SABRE: the Semi-Automated Business Research Environment.

IBM would go on to develop similar systems for Delta Air Lines and Pan American World Airways in the 1960s. By the 1980s the SABRE system was used by CompuServe; by 1990s it was employed by America Online.

In 2000, Sabre became a separate corporate entity under the name Sabre Holdings—and one of their assets is that well-known online booking company, Travelocity.