Tragedy Over Texas

A new book details the loss of space shuttle Columbia 15 years ago, and the heroic search operation that followed.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/32/2b/322b9826-445a-4828-89ab-3577c2e1e4f8/debris_in_sky.jpg)

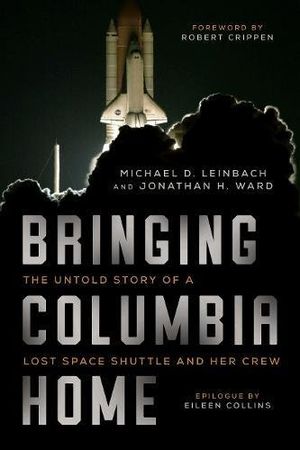

In their riveting new book, Bringing Columbia Home: The Untold Story of a Lost Space Shuttle and Her Crew, former NASA launch director Michael Leinbach and Jonathan Ward chronicle the loss of space shuttle Columbia on February 1, 2003, and the subsequent search operation, the largest in U.S. history. This condensed excerpt focuses on the first few hours after the accident, which occurred shortly after 8 a.m., Texas time, as officials struggled to realize what had happened, and before an army of citizen volunteers joined in the search, which would go on for weeks.

Accident Plus Twenty Minutes

In Tyler, Texas, Jeff Millslagle laced up his shoes for a training run for the upcoming Austin marathon. A rumbling sound startled him. As a California native, he at first thought it was an earthquake. But as the noise continued, he realized it was unlike anything he had ever heard.

Millslagle was one of the FBI’s senior supervisory resident agents in Tyler. His colleague Peter Galbraith phoned him and asked, “What the hell was that?” They speculated that perhaps one of the pipelines running through the area had exploded. It seemed the only likely explanation. It was certainly not tornado weather. No other natural phenomenon could have caused such a prolonged banging.

Millslagle phoned the Smith County sheriff’s office to see if they had any reports of unusual activity. They checked and phoned back, “It was the space shuttle reentering.” That didn’t seem plausible, since the shuttle’s sonic booms wouldn’t be audible at sea level until the shuttle was well east of them. The sheriff’s office called again a few minutes later. “The shuttle broke up overhead. There are reports that Lake Palestine is on fire.”

Millslagle turned on his TV and saw video of Columbia disintegrating. He immediately phoned Galbraith and told him they needed to meet at the FBI office in Tyler.

_____________

In Sabine County, Texas, Greg and Sandra Cohrs sat down to breakfast and turned on their television. Reports began coming in that Columbia had “exploded” over Dallas. Grass fires were springing up in the area. Greg said to Sandra, “I bet we’ll be involved in this before it’s over.” US Forest Service personnel, regardless of their job titles, typically were called in to help respond to all-risk or all-hazard incidents—wildfires, hurricanes, floods, and even terrorist attacks—in their local communities and across the nation.

Cohrs called the district fire management officer to find out if he should report for work. The officer said he was waiting for a call and told him to stand by. In the meantime, Cohrs prepared to do his usual Saturday yard work, but then a call back informed him that he would be on flight duty that day as a spotter.

Cohrs brought up the Intellicast weather radar website on his computer as part of his usual preflight routine. Despite the clear blue sky above, the radar image showed a wide swath of something in the air along a northwest to southeast track from Nacogdoches, Texas, through Hemphill and heading on toward Leesville, Louisiana. The largest concentration of radar returns was centered over Sabine County, and the cloud appeared to be slowly drifting north and east. He realized that the weather radar was picking up the debris from Columbia that was still falling to the ground. He took several screen snapshots of the radar display.

Accident Plus Thirty Minutes

Things were going crazy in East Texas. In his office in Hemphill, Sheriff Maddox desperately needed to figure out what was happening in Sabine County. A deputy had just come on duty, and Maddox immediately dispatched him to the north end of the county. He phoned law officer Doug Hamilton from the US Forest Service and asked him to check on a possible train derailment near Bronson in the western side of the county. Maddox hopped in his car to head for the nearby natural gas pipeline. His dispatcher radioed him and said, “NASA just called and said it wasn’t a pipeline explosion. That was just the shuttle going over and breaking the sound barrier. You can go about your regular duties.”

Maddox drove over to Hemphill’s youth arena to see what was going on at the livestock weigh-in. People asked him what it was that had passed overhead. Maddox told them it was the shuttle breaking the sound barrier. One woman said, “But they haven’t heard from it in fifteen minutes.”

Maddox knew something was wrong. He got back in his car. The dispatcher radioed that people were calling in from all over the county about items raining down from the clear blue sky, breaking tree limbs, and hitting the ground.

Phone calls began pouring in to the town’s volunteer fire department in addition to those coming in to the sheriff’s office. “There are things falling out of the sky!” “Something just hit the road!” Then news of Columbia’s loss came through. The firefighters debated for several minutes about what to do. Volunteers started heading out to investigate the calls and secure the items being found.

Hemphill City Manager Don Iles arrived at the fire station as a radio report came in from a Texas Department of Public Safety (DPS) officer on US 96 near Bronson. “There’s a big metal object in the middle of the highway. It gouged the road. I’m looking at it, but I don’t know what to make of it.”

The dispatcher asked if it had any identifying marks or numbers. The DPS trooper said, “Yeah, but it’s only partial.” He read back the numbers to the dispatcher, who then told him to wait. The trooper said he would stay at the scene by the object and keep vehicles from running over it.

A few minutes later, the dispatcher came back on and said, “I’ve just been in touch with NASA. Please do not pick up or touch any of the material, because it could be radioactive or poisonous.” There was dead silence on the other end of the radio as the trooper pondered his situation.

Doug Hamilton arrived at the site of the reported train derailment, about five miles from his house, but there were no trains in sight anywhere. He called back to the sheriff’s office and was asked to head to the wreckage sighting on US 96.

Sheriff Maddox and Hamilton met the DPS trooper at the scene. The metal object was the waste storage tank from Columbia’s crew module—the first confirmed piece of the shuttle found in Sabine County.

With the nature of the situation now confirmed, the accident scene in Sabine County officially became a federal incident. Hamilton, as a federal law enforcement officer, was now the man in charge.

Hamilton photographed the tank, and he and the others cordoned off the area with crime scene tape. They recorded its GPS position and called it back in to the dispatcher. Maddox and Hamilton had no officers available to guard the wreckage. The three men drove off together in Hamilton’s government car to investigate the next reported sighting.

Someone overheard their radio report. When officials came back later in the day to retrieve the waste tank, it was gone.

Hamilton, Maddox, and the trooper next responded to a call from a woman’s farm outside Bronson. She had found partial human remains in her pasture. The sheriff went to the farmhouse and asked the family for a sheet to cover the remains. Someone suggested that they be removed from the pasture. Hamilton refused. “No, we ain’t movin’ nothin’! This is a crime scene.” He now knew that the gravity of the situation required more than just taking photos and recording GPS locations. He photographed the remains and placed a sheriff’s department officer on guard.

Hamilton and Maddox drove from scene to scene for the next several hours, meeting DPS troopers at the location of each reported sighting. A few findings appeared to be partial remains of the crew, but most were pieces of the shuttle.

At one house, an aluminum I-beam had fallen through the carport roof, broken through the concrete floor, and buried itself in the ground. This eventually turned out to be the only structural damage sustained anywhere in Sabine County.

At that time, Hamilton was the only law officer in Sabine County who had a digital camera. After visiting the first six or seven scenes, Hamilton had already filled two data disks with photos. He realized it would be physically impossible for him to visit all the debris sightings, especially now that he knew bodies were on the ground. And there were not enough law officers in Sabine County to guard every piece of debris being discovered.

Accident Plus One Hour

Astronauts Mark Kelly and Jim Wetherbee were at their suburban Houston homes when contact with Columbia was lost. Both immediately knew the situation was dire. They rushed to the astronaut office in Building 4 South at Johnson Space Center.

As quintessential type A personalities, astronauts are biased toward acting to bring a situation under control. Patience can be a tough virtue for them to exercise, especially when the lives of their colleagues are on the line. While they awaited official orders, the astronauts at JSC took whatever actions they could. Mark Kelly and rookie Mike Good brought out the contingency checklist and reviewed the required actions. Working through the list, Kelly and Good made phone calls, and within fifteen minutes, nearly fifty people were in the astronaut office conference room. Discussions began on how to farm out the astronauts to locate Columbia’s crew.

Several of the astronauts decided to head to Ellington Field, about halfway between JSC and Houston. Ellington was the home base for the T-38 jets the astronauts flew around the country. Wetherbee drove home to pick up his flight suit and pack his overnight bag, and then drove to Ellington to await orders.

Kelly pointed out to Andy Thomas, the deputy chief of the astronaut office, that the contingency plans never envisioned the shuttle coming down within a two-hour drive of Houston. Kelly said, “We really need to send somebody to the scene right now.”

Thomas said, “Okay. You go.”

Kelly considered his options for getting north to the accident scene as quickly as possible. He phoned Harris County constable Bill Bailey and requested a helicopter. Bailey made a few calls and phoned back. “I’m sending a car to pick you up. The coast guard is going to take you up there.” Kelly grabbed astronaut Greg “Ray J” Johnson to accompany him. They arrived at Ellington Field and boarded the waiting helicopter.

As they took off, the pilot asked, “Where are we going?”

Kelly said, “I heard there’s debris coming down at Nacogdoches. Let’s go to the airport there.”

Accident Plus Three Hours

Mark Kelly’s coast guard helicopter set down on Hemphill high school’s football field. Kelly went into the school gym, where a basketball game was in progress. He found a policeman and asked to be taken to the town’s incident command center. The policeman escorted him to the firehouse, about one-quarter mile south. Kelly introduced himself to the FBI’s Terry Lane, who had also just arrived in town.

About three hours after the accident, a call had come in regarding a sighting of something unusual on Beckcom Road, a few miles southwest of town. A jogger had seen what he first thought to be the body of a deer or wild boar near the roadway.

Kelly and Lane rode with Sheriff Maddox to the site. They met Tommy Scales from the Department of Public Safety, who had just come from another debris scene nearby.

They encountered what was clearly the remains of one of the Columbia’s crew. Maddox radioed John “Squeaky” Starr, the local funeral director, to come to the scene to assist in the recovery. Kelly also requested that a clergyman come to the site to perform a service before the remains were moved or photographed. While they were waiting, another state trooper covered the crew member with his raincoat.

“Brother Fred” Raney, the pastor at Hemphill’s First Baptist Church, had just returned to the firehouse to report that he had seen partial remains of a Columbia crew member in a pasture. Raney drove out to join the officials gathered at the Beckcom Road site. He conducted a short memorial service for the fallen astronaut.

By now, the news media had arrived in the area and were monitoring police radio frequencies. They intercepted the call about the Beckcom Road remains, and a news helicopter full of reporters flew over the scene, trying to get video of the recovery on the ground. They were low enough, and their motion deliberate enough, that it was clear to the people on the ground that the pilot was trying to use the helicopter’s rotor wash to blow the raincoat from the crew member’s remains. Lane and two troopers stood on the corners of the coat to keep it in place. One of the troopers used “an emphatic gesture” to make it clear to the pilot that the helicopter had to leave the area immediately.

Lane later said, “I don’t know if a helicopter has ever been shot down by a DPS pistol, but they were very close to that happening.”

The troopers noted and reported the tail number of the helicopter. Shortly thereafter, the FAA ordered a temporary flight restriction over all of East Texas.

After the remains were placed in a hearse, Kelly, Lane, and Raney moved on to a house near Bronson, where partial remains of another crew member had been reported. The media had intercepted those radio calls, too, and several reporters were on the scene when the officials arrived. From that point forward, the command team began using code words and decoy vehicles whenever crew remains were being investigated.

Lane was a veteran of the FBI’s response to many horrific accidents, including the TWA 800 crash and the World Trade Center attacks. His orders in East Texas were to work as part of a team of four individuals: himself, a forensic anthropologist, a pathologist from El Paso, and a Texas Ranger. Whenever a call came saying, “We think we found something,” the team’s role was to ascertain how likely it was that the finding actually was human remains. The team deployed all necessary resources to make a recovery of any remains that were probably or likely to be human.

Making the first two crew remains recoveries in the space of a few hours set the tone and protocol for subsequent recoveries. From that point forward, whenever possible crew remains were located, the FBI would be called to the scene immediately. An astronaut accompanied Lane and his team to investigate every sighting, without exception.

A Texas Ranger or DPS officer, Brother Fred, and a funeral director (either Squeaky Starr or his son Byron) would meet the FBI evidence recovery team and astronaut at the site. Once the group was assembled, the scene was turned over to the astronaut to step forward and preside over the recovery of his or her colleague. When the astronaut was ready, he or she would signal Brother Fred to approach, who then performed a brief service offering a few words on the heroic sacrifice of the crew member, reading certain verses from Scripture, and then saying a prayer. The astronaut then released control of the scene to the FBI evidence team. The remains were placed in a body bag and taken to a hearse. Squeaky or Byron Starr would then transport the crew member’s remains to a waiting doctor.

Brother Fred learned that Columbia’s commander Rick Husband had recited Joshua 1:9 to his crew as they suited up before their flight: “Have I not commanded you? Be strong and of good courage; do not be afraid, nor be dismayed, for the Lord your God is with you wherever you go.” Brother Fred incorporated that verse into all of his services in the field. He and Kelly also researched appropriate words to say for Hindi and Hebrew services. All the services delivered in the field after the first day included Christian, Hebrew, and Hindi prayers.

Lane was deeply moved by the way the astronauts handled the recoveries. He knew how horribly difficult it must have been for them to see their friends and colleagues in that condition. It was a duty far outside the scope of what any astronaut would normally be asked to perform. The strength of the astronauts’ religious convictions also surprised Lane at first. Then he realized that if these people “strap a million pounds of dynamite to their butts for someone else to light, they’d better have a mighty deep faith.”

Accident Plus Five Hours

President Bush addressed the nation from the White House Cabinet Room at 2:04 p.m. Eastern Time. “My fellow Americans,” he began, “this day has brought terrible news and great sadness to our country. At nine a.m., Mission Control in Houston lost contact with our space shuttle Columbia. A short time later, debris was seen falling from the skies above Texas…

“The Columbia is lost. There are no survivors.”

Bringing Columbia Home: The Untold Story of a Lost Space Shuttle and Her Crew

Timed to release for the 15th Anniversary of the Columbia space shuttle disaster, this is the epic true story of one of the most dramatic, unforgettable adventures of our time.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.