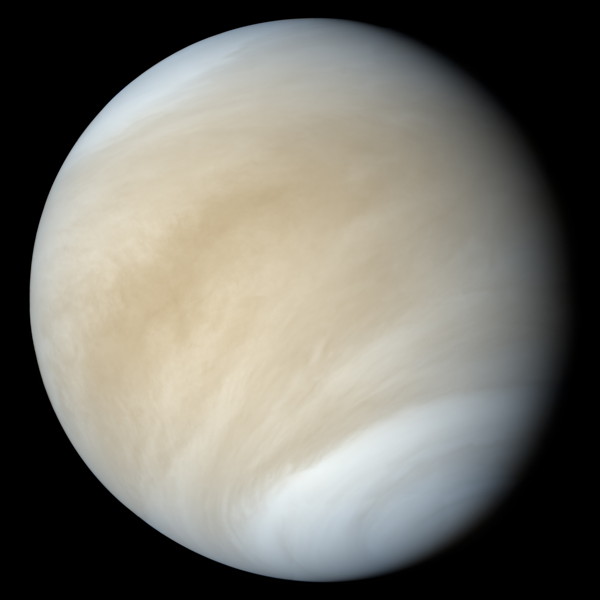

Transit of Venus, Then and Now

When you drive to your local observatory to witness the Transit of Venus on Tuesday, spare a thought for the men who sought to witness the spectacle in 1761.

When you drive to your local observatory to witness the Transit of Venus next Tuesday, spare a thought for the men who sought to witness the spectacle in 1761. As Andrea Wulf writes in her new book Chasing Venus: The Race to Measure the Heavens, in 1760, astronomer Joseph-Nicolas Delisle asked his colleagues to participate in an international collaboration to observe the transit of Venus.

Jean-Baptiste Chappe d’Auteroche, slowly making his way from France to Tobolsk, Siberia,

“endured a cold he ‘had not before experienced.’ Even inside the carriage the temperatures were so low that one day he fumbled out his thermometer with numb fingers and scrawled in his journal ‘eleven degrees below 0.’ He had to wade waist-high through sluggishly floating ice when the carriage crashed through the frozen surface that had transformed the rapid rivers into temporary roads—probably no surprise given that the instruments alone weighed more than half a ton. The hilly roads on land posed other problems as they were covered ‘from top to bottom’ with an icy glaze. Even when they put all ten horses in front of one carriage, they found they couldn’t move it. Much of the way through the mountains they had to walk, slipping and falling, and were soon covered in bruises. Sometimes strong winds blasted clouds of snow high up into the air, whipping the flakes into frozen pellets. The coachman, who was most exposed to the frosty assault, ‘could not stand it’ and ran away.”

Or this poor guy, Anders Planman, traveling from Sweden to Kajana, Finland:

“To reach Finland, he had to cross the frozen Gulf of Bothnia by sledge, but the severe winter had laid an unusually thick blanket of snow over Scandinavia. The whipping waves had congealed into a frosted picture, as if someone had snapped a finger to stop the world. In place of a smooth surface the Gulf of Bothnia was a treacherous icescape of ‘superb stalactites of a blue green colour.’ Though stunningly beautiful, it made for dangerous traveling. Sledges had to follow the hardened lines of the waves, regularly overturning when one side would suddenly be ‘raised perpendicularly in the air.’ Wrapped up in thick pelts, the passengers were often catapulted out of their sledges like furry cannonballs and the horses then galloped off, scared, as another traveler described, ‘at the sight of what they supposed to be a wolf or bear rolling on the ice.’”

Observers in North America will see the transit of Venus the evening of June 5th. You can download a free Transit of Venus phone app here.

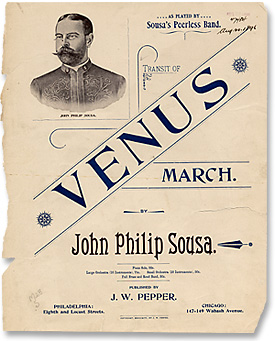

Want some musical accompaniment? Listen to a recording of John Philip Sousa’s “Transit of Venus March,” courtesy of the Library of Congress. The piece was composed in 1883 in honor of Joseph Henry, the first Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution.