Truck Killer

For one mission in Vietnam, the best aircraft for the job was a bomber from World War II

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Truck_Killer_FLASH.jpg)

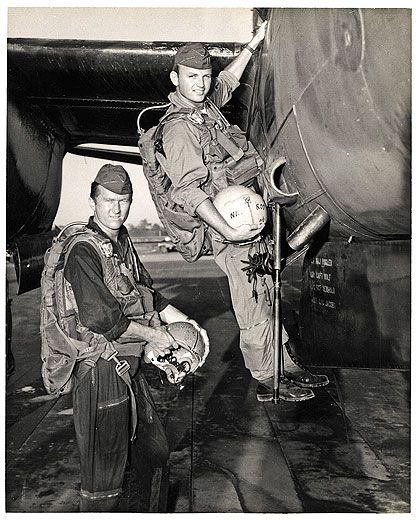

“I was born 25 years later than I should have been,” muses former U.S. Air Force pilot Tim Black, a veteran of two tours in Vietnam. “I grew up enamored with World War II pilots and planes.”

Born late or not, Black flew combat missions in a World War II airplane. Dropped World War II-era bombs. Even fired leftover .50-caliber World War II bullets.

But that’s not why he volunteered to fly the Douglas A-26 Invader in Southeast Asia in the 1960s. In fact, at the 2009 Air Commando Association reunion in Fort Walton Beach, Florida, every crewman asked said that the old bomber’s appeal had nothing whatsoever to do with historical legacies. “A-26s were the best for the mission,” says pilot Jay Norton, echoing the sentiment of all on hand.

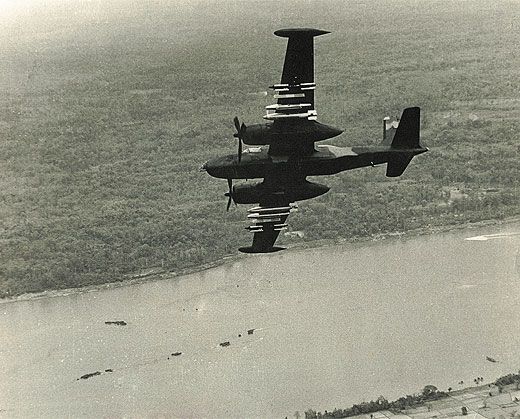

Even in the fast company of F-4s and F-105s, as well as many other types that attacked traffic on the Ho Chi Minh Trail, the A-26 became known as “the best truck killer in Southeast Asia.” It had just the right combination of firepower, loitering time, and ruggedness.

In November 1940, the Army Air Corps asked the designers at Douglas Aircraft to create a replacement for their own A-20 Havoc light bomber and, if possible, to surpass North American’s B-25 Mitchell and Martin’s B-26 Marauder as well. “Engineers and technicians tried to make sense of the comments from the field regarding the shortcomings of the A-20, B-25, [and] B-26, and shape a next-generation aircraft,” says Dan Hagedorn, senior curator at Seattle’s Museum of Flight. “The A-26 was far more agile than any of these three, and flew more like a fighter.”

After an impressive prototype dazzled the brass by exceeding performance parameters and out-performing the A-20, the government immediately placed an order. But when design changes and tooling difficulties delayed production, excitement stalled. And challenges in the manufacture of the airplane’s wing spars (not the last time wing spars would haunt the A-26’s story) kept production exasperatingly slow. So slow that General Hap Arnold, commander of the U.S. Army Air Forces, groused, “I want the A-26s for use in this war, not the next war.” The irony, of course, is that Invaders would fly in the next war—and the next.

But the aircraft did make it into World War II. In late 1944 and early 1945, A-26s reached the European theater and the Pacific. The aircraft had a crew of three—pilot, navigator, and a gunner who operated upper and lower remote-controlled turrets much like a B-29’s. Pilots came to appreciate the A-26’s agility and punch. But the various delays kept the total number built by the end of World War II relatively small, with only 2,451 put into service—a quarter of the number of B-25 Mitchells.

In 1948, the military made a switch that would lead to confusion among historians for years to come: The A-26 was redesignated the B-26. The confusion still persists. The B-26 Marauder, manufactured by Martin during World War II, had been retired from the Air Force inventory by 1948. Decades later, John Moench, a retired major general who had been in the Air Materiel Command early in his career, wrote an explanation for the B-26 Marauder Historical Society: “[The Air Force] had no trouble converting a P-51 to an F-51 or a P-80 to an F-80. But, when it [came] to the A-26, there was a dilemma. To preserve the Martin B-26 ‘Marauder’ nomenclature, following my suggestion, the initial attempt…was to pick up a new number…as the next numbered ‘B’ in the sixty series. But [others] did not like this as it upset the progressive numbering attached to advancing design…. As a result, with a lot of reluctance and since there was no Martin B-26 ‘Marauder’ left in the inventory…[the Douglas] ‘A-26’ became the B-26. I resisted the idea as long as a major could, but I never foresaw the extent to which later confusion would arise.” Adding to the confusion, the Invader would have its “A” (for “attack”) designation restored in 1966. To this day, all who flew the Invader from the late 1940s until the early 1960s—including the prologue of Vietnam—still call the aircraft the B-26; those who flew it earlier and later call it the A-26.

About 450 Invaders saw frontline action during the Korean War. The airplane had its problems—especially a top speed half that of the 687-mph F-86 Sabres and MiG-15s—but found a niche in truck and train destruction. The B-26 dropped the first bomb in North Korea and the last bombs of the conflict, just before the armistice in 1953. Then most went straight to storage, or were sold to other countries for counter-insurgency duties.

Early in the Vietnam War, most Invaders were essentially still in their World War II configurations, but without a gunner’s position and the two gun turrets.

From late 1961 through 1964, the old airplane flew mostly in bombing and close-air-support roles against guerilla concentrations—an operation code-named Farm Gate. Initially, the unit was benignly called the 4400th Combat Crew Training Squadron (a Vietnamese airman was required to fly in the third seat, behind the navigator, to uphold the pretense of training), and eventually was renamed the 1st Air Commando Wing.

When Air Force crews arrived in Southeast Asia, some of the 25 Invaders that saw action during Farm Gate were already there, likely ones that the CIA had used for clandestine operations in Laos and elsewhere. “The airplanes were old, and not in very good shape,” recalls Gary Pflughaupt, a navigator who arrived at Bien Hoa, the Farm Gate base near Saigon, in November 1963. “Minor maintenance had been done, but the structural aspect of the airplane was never checked, and ultimately there was metal fatiguing. They were just falling apart.”

Tom Smith, a pilot who arrived in July 1963, recalls, “When I stepped off the plane at Bien Hoa, I heard something overhead and looked up to see a B-26 coming into the landing pattern. As he pitched out [peeled off], the plane made this whistling sound. I thought he had a turboprop engine. As it turned out, what I heard was air passing over the holes in the plane—they whistled like when you blow over a bottle.”

Losses on several missions raised questions about causes, but no crew had survived to tell if they had been brought down by enemy action or structural failure. “There was some suspicion of [failure], but because of the way the airplanes were lost, nobody ever saw it happen,” says Pflughaupt. “The presumption was they were shot down.” A lot of stories from forward air controllers, or FACs, both Vietnamese and American, hinted otherwise.

The squadron kept flying. “They put a big old G-meter up there in the cockpit and we weren’t to exceed 3.5 Gs,” Smith says. For self-preservation, pilots obeyed. Did crews worry? “I didn’t pay any mind to the wing,” says Smith’s navigator, Francis Hayes. “It was the guys on the ground shooting at us that I worried about.”

On typical night bombing missions to the Mekong Delta, there were plenty of guys on the ground shooting. “Particularly when you dropped napalm,” says Hayes. “You knew you’d take fire because it would light up the underside.” Smith says his aircraft returned with battle damage “all the time, often near the trailing part of the wings or rear fuselage. Small arms, .50-cal. A whole unit would stand up and fire a burst.” Hayes has firsthand proof: a spent .45 round that came up through the Invader’s cockpit floor. It was the caliber used in Thompson machine guns, M3 “grease guns,” and various others in the hands of the enemy. The A-26’s underside was not armored, and the round tore through the thin aluminum easily. Hayes reflects, “If they shot at you, you knew you were in the right spot.”

The unit had “one and a half crews per bird”—enough, Hayes recalls, for crews to fly about every other night. But suddenly, in February 1964, an urgent order cancelled all missions.

“The final straw was when a B-26 wing came off on a demonstration flight on Eglin’s Range 52,” says Pflughaupt, referring to Hurlburt Field, an auxiliary field of Florida’s Eglin Air Force Base where B-26 crews were trained. The cause of the crash: wing spar failure. The airplanes were grounded.

This could have spelled the end of the Invader story, but instead the Air Force awarded a $16 million contract to a company called On Mark Engineering in Van Nuys, California, to rebuild 40 B-26s. Most Invaders picked for makeovers came from the boneyard at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base in Tucson, Arizona, where, according to Hagedorn, 300-some Invaders were parked in the ready-for-ingots section. The new designation: B-26K.

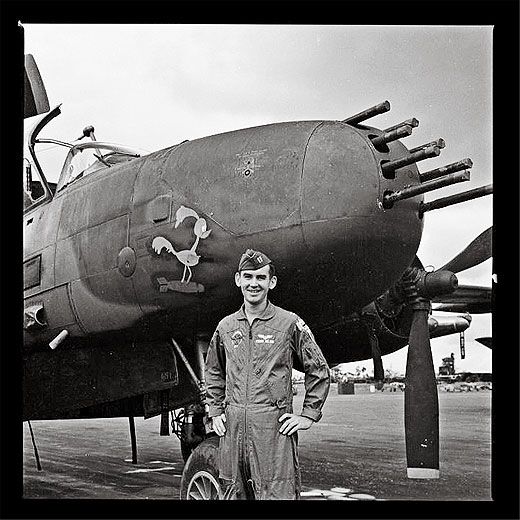

Visible changes included permanent wingtip tanks, a slightly taller rudder, new underwing pylons, eight .50-caliber machine guns in the nose, dual controls (as opposed to pilot side only), new instruments, and radios. Invaders that still had dorsal and ventral turrets lost them. Performance modifications included improved Pratt & Whitney R-2800-52W radial engines with water injection and 2,500 horsepower (replacing the 2,000-hp version of the R-2800s) with fully reversible Hamilton-Standard props. The contractor also partially rebuilt the fuselage and tail, redesigned the wings, reinforced wing spars, and installed brake components from the much larger KC-135. No more G-force restrictions.

Smith and Hayes picked up a fresh B-26K directly from On Mark at Van Nuys Airport. “It was like a spanking new airplane—smelled like a new Volkswagen,” Smith says. He thinks for a moment, then continues: “The plane flew the same. But more gee-whiz. More powerful, more solid—you could tell in the takeoff. A good bit more power. And you could carry more.”

You could not only carry more, you could also carry it faster and farther: Maximum armament load increased from 7,500 pounds to 12,000—still 4,000 pounds internal, but now 8,000 under the wings. Maximum cruising speed went up to 305 mph, 29 mph faster. And thanks to the wingtip tanks, combat radius increased to 575 miles, up from 241.

The K model came packing an extra-wide variety of ordnance, from LAU-3A rocket pods to 750-pound M117 general-purpose bombs—and a whole lot of attitude. It also carried several thousand rounds of .50-caliber ammunition for the eight nose guns. Favorites for truck busting were the World War II M31 and M32 thermite incendiary clusters (referred to as “funny bombs” and shaped like water heaters with fins) and 500-pound BLU-23 and 750-pound BLU-27 finned napalm bombs.

“I don’t know of anyone who wanted to bring ordnance back home,” says Jay Norton, who arrived in Southeast Asia with navigator Tom Bronson in January 1968. Both had completed an overseas tour and were teamed up during training at England Air Force Base in Louisiana after they chose A-26s. “I had flown C-7 Caribous,” Norton says. “The first time I got shot at, I searched for a way to shoot back. That’s how I decided on A-26s.” Bronson opted for the Air Commandos after seeing A-26s lighting the trail on C-130 flareship missions.

When the Counter Invader debuted in Southeast Asia in 1966—the 609th Air Commando Squadron later absorbed the mission—it became known for its permanent call sign: “Nimrod,” a Biblical reference to Noah’s great-grandson, “a mighty hunter.” Thereafter fliers in the unit were called by the same nickname: The Nimrods.

They were based at Nakhon Phanom in eastern Thailand. The Royal Thai government did not want “bombers” based there flying against its neighbors, so in May 1966 the Invader’s name changed from B-26K back to an attack designation, A-26A, since an attack plane was not technically a bomber. Besides, the airplane didn’t look like a bomber; it was much trimmer and sportier.

Shortcutting through Thailand’s neighbors Laos and Cambodia, the Ho Chi Minh Trail was a vital artery for communist supplies that were being shuttled from North Vietnam to South Vietnam. It has been called an ingenious logistical network: mostly hidden under the jungle canopy, trucks could travel on dirt or gravel roads that split into multiple routes, with numerous truck parks, fuel and ammo dumps, barracks, and command facilities along the way. U.S. commanders realized night interdiction here was crucial, and “choke points” on the trail in Laos became prime hunting grounds.

Bronson describes an average night over the trail: “We typically flew at 5,500 to 6,500 feet, navigating with TACAN [Tactical Air Navigation, which provided bearing and range], and we’d drop to 2,000 to 3,000 feet over the target area. The FAC would drop one to three logs [ground flares that glowed like firewood].” The controller then radioed the elevation of the target, terrain, and obstacles to look out for, and recommended attack and exit headings. “The FAC used a starlight scope to help him see movement on the trail, and he’d radio where it was, saying, ‘Trucks are 100 meters northeast of the log.’ ”

The navigator armed the ordnance, and the pilot nosed the A-26 down into a 30-degree dive. During descent, the navigator would call out altitude while the pilot concentrated on the logs and rapidly approaching target. “Then I’d pickle and pull [drop the bombs and climb],” Norton says. Sometimes a single truck would go up in flames, sometimes a huge secondary explosion indicated a hit on a truck park, and other times a pass resulted in just a cratered moonscape.

During this time, A-26s flew individually, taking off at intervals through the night to fly over assigned sections of the trail. “But we were far from alone,” says Bronson. Besides the FAC flying in an O-2, C-123, or C-130, the A-26s might be joined by “a C-130 dropping flares, Navy A-4s that didn’t have targets in Vietnam, [or] our own F-4s and B-57s over the trail. It could be quite crowded airspace. Mid-air collisions were a real concern. We went through jet wash sometimes.”

While the fast movers came and went quickly, A-26s stayed over the target area. “With plenty of gas, we could wait for something to develop,” says Norton. That also gave enemy gunners plenty of time to take aim. Enemy action and other causes brought down a dozen A-26As. Crews routinely took fire from unseen 37-mm and sometimes larger guns, hidden by the darkness and jungle canopy. “The longer the tracer gets when it goes by, the closer it is,” Norton says. “When we saw tracers coming closer, I would break left or right.”

Norton shares one of the tricks for flying the twin-engine Invader: “To keep the gunners guessing…we kept the props out of sync. It causes a hmmm mum mum sound that, to a person on the ground, is very hard to tell where the sound is coming from.” But even the best tricks could not always stop determined North Vietnamese gunners from finding their mark; still, when they did, “the airplane was terribly rugged—it brought you back home,” says Norton.

Just ask Ken Yancey. His aircraft sustained battle damage bad enough to warrant the complete replacement of his tail section—three times. All were 37-mm hits to the stabilizers—vertical, horizontal, or both—followed by bone-shuddering flights back to Nakhon Phanom. But in 217 missions, enemy gunners never brought Yancey down.

He has only praise for the airplane. “It was like flying a fighter,” he says. “The airplane would do what I wanted it to do.”

“Such a nice plane to fly,” says Smith. “You won’t find anybody who’s flown it that wasn’t really impressed with it—before or after the conversion. It had a mystique, a charm to it. It’s what brings us here [to the reunion].” Smith’s claim held up at every table of the reunion’s hospitality room (or as the attendees called it, the “hostility room”). Pressed to identify the airplane’s vulnerabilities, they grudgingly gave up only two: “no ejection seats” and “too slow for daytime.” “Our salvation was flying in the dark,” says navigator Frank Nelson.

The push for an all-jet air force is what some Air Commandos believe brought an end to their missions in November 1969 and retirement of the A-26. The warplane had seen service in three wars spread across three decades, never quite getting pushed out of the inventory because it always managed to find a niche, even while performing its work in the same low-tech, dive-bomb, shoot-’em-up way it had since World War II. This time, though, the airplane would stay retired for good.

Tim Black and his navigator, Bruce “Gus” Gustafson, ferried one of Nakhon Phanom’s 15 remaining A-26s back to the States, island-hopping across the Pacific with fuel stops at some legendary World War II locales: the Philippines, Guam, Wake, Midway, and Hawaii’s Hickam Field. The two had trained as a crew, flown combat as a crew, taken Combat Time Off together in Bangkok. And together they brought home an A-26. One night at the reunion, seated side by side (perhaps because it felt most natural, Gustafson in the right-hand chair—the A-26’s navigator’s position), they tell the story: “We landed at Davis-Monthan and taxied over to the boneyard side of the base,” Black recalls. “We went through some gates where you’re supposed to park your airplane to get it ready to put into storage. A guy chocks us, then comes over and says, ‘Shut ’em down.’ We say, ‘No.’ He says, ‘Shut ’em down.’ After several nos, the guy finally walks off and leaves us sitting there.”

The two glance at each other, flashing back to a moment frozen in time, circa January 1970, and say in unison, “We still have gas.” Then Gustafson chimes in, “And it’s still our airplane.” Black shrugs, “And it might be the last time this airplane flies.” The pair remembers staying there 15 or 20 minutes more, just sitting in the cockpit, with the engines running.

A senior researcher at National Geographic magazine, David Lande wrote "Live and Let Fly" (Aug./Sept. 2008).