Tullo and the Giant

For pilots shot down over North Vietnam, the way home was jolly and green.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/tullo-main.jpg)

Frank Tullo has never forgotten his first day as a captain. He was 25 years old and flying from Korat Royal Thai Air Base, one of two F-105 bases in Thailand. News of his promotion had come through late the evening before, and he had sewn a pair of shiny new captain's bars on his flightsuit. He was wearing those bars when North Vietnamese gunners on the outskirts of Hanoi shot him down.

I heard Tullo's story a few years ago when he was an airline captain and I was negotiating the sale of radios to his airline. I flew 122 missions in F-4E Phantom IIs, also out of Korat but at a later time in the war. Many of my friends had been shot down over there, and a lot were never heard from again. Most fighter crews were not optimistic about their chances for rescue.

Pilots of the F-105 Thunderchief, or "Thud," in particular, suffered a high loss rate. There was a standing joke among the often chain-smoking Thud crews that the definition of an optimistic Thud driver was one who thought he would die of lung cancer. In fact, the Air Force commissioned a study that showed that during a typical 100-mission tour, an F-105 pilot should expect to get shot down twice and picked up once. At about the time that Tullo got his captain's bars, air rescue planners decided to try to improve the pilots' chances.

On July 27, 1965, Tullo was flying as Dogwood Two in a flight led by his good friend Major Bill Hosmer, a former Thunderbird and the best pilot Tullo had ever flown with. Dogwood was to be the cleanup flight--the last of 24 F-105s, six flights of four, from Korat to hit surface-to-air missile (SAM) sites in North Vietnam. Their job, as cleanup, would be to take out any sites not destroyed by the earlier flights.

The SAM had introduced a new aspect to the war only days before, when an F-4 Phantom II became the first to fall to these new weapons. The missiles were fired from within a no-fly zone near Hanoi, previously immune from attack as dictated by rules of engagement. Tullo's flight would be part of the first attack within the no-fly zone and the first major strike on the SAM sites since the Phantom had been downed.

To destroy the missile sites and take out their command and control centers, each Thud was loaded with two pods of 2.75-inch rockets. (They were also equipped with an internal 20-millimeter Gatling cannon.) Along with the rockets, the Thuds carried 450-gallon auxiliary fuel tanks under their wings. Tullo's aircraft, which was scheduled to be flown to Okinawa for maintenance, also carried a 600-gallon tank on its centerline. He'd have to jettison the tank once airborne to stay with the flight.

This was part of a maximum effort involving at least 48 F-105s--24 from Korat and 24 from Takhli--and another 50 or so supporting aircraft. At this early stage of the war--the buildup of U.S. fighters in Thailand and South Vietnam had begun only six months before--tactics and weapons for dealing with SAMs had not been developed. The projected learning curve for the months ahead was nearly vertical.

It was mid-afternoon when Tullo's flight came over the hills from the south to clean up leftover targets. Dogwood flight had been listening to the action on the assigned attack frequency since an in-flight refueling midway en route. From the sound of things, some friendly aircraft were down. As the flight cleared the last ridge at treetop level before arriving at the target area, Hosmer, who was Dogwood lead, exclaimed, "Jesus!"

Working to hold his position on Lead's wing, Tullo managed to steal a look ahead. "I damn near fainted," he told me years later. "To a good Catholic boy, this was the description of hell." The whole valley was a cauldron of flame and smoke from the ordnance dropped by preceding flights, and North Vietnamese Army flak filled the sky. In the five months he had been in the war, Tullo had seen his share of anti-aircraft artillery, but this was the worst yet.

Hosmer had the flight on course for the first SAM site they were to check out. Tracers were flying past the canopies and the smell of cordite was strong--the pilots depressurized their cockpits when they neared the target area so that if hit, smoke from an onboard fire would not be drawn inside. Only days before, Tullo had seen a column of smoke stream from his wingman's still-pressurized cockpit after the canopy was jettisoned prior to ejection.

The flight pressed lower. The Thud would do nearly 700 mph on the deck. Tullo was sure they were under 200 feet and was working hard to stay in position on Lead.

Without warning, Hosmer broke hard left, exclaiming "Damn, they just salvoed!" Sometimes SAM batteries would fire all their missiles at once in an effort to save the valuable control vans. Tullo could see only the huge wall of smoke and flame coming at the flight from the NVA guns protecting the SAM sites.

Their tremendous speed caused the flight to turn wide enough to be carried directly over the gunsite. As they passed over, Tullo looked right into the flaming muzzles of a battery of quad guns. They were at 100 feet or lower, and still near 700 mph. He glanced over at Lead to check his position, then back into his cockpit. That's when he noticed the fire warning light.

"Lead, I have a fire light," he radioed.

Three called, "Two, you're on fire. Get out!"

Hosmer kept the flight in the turn, saying, "Two, loosen it up. I'm going to look you over."

Tullo assumed the lead and headed for the mountains in the distance. Hosmer said, "Better clean off the wing, Frank." To give himself more speed and maneuverability, Tullo jettisoned the tanks and rocket pods on his wings and felt the Thud lighten.

Three was calling again, his voice tight with urgency.

"Two, the flames are trailing a good 150 feet behind you. You better get out!" In spite of the fire and the calls from Three, Tullo felt a sense of well-being. He was still flying, he had control, and he was with Hosmer. Nothing bad would ever happen with Hoz leading. It would work out. The fire would go out, the aircraft would keep flying, he would make it back. They were still over Hanoi. Houses were below them. The mountains to the west, which would come to be known as Thud Ridge, offered refuge. A good bailout area, just in case.

"You better get out, Frank, it's really burning," Hosmer said in a calm voice.

"Negative," Tullo replied. "It's still flying. I've lost the ATM [the noisy auxiliary turbine motor, which provided the Thud's electrical power but left many of the aircraft's pilots with bad hearing], but I've got the standby instruments, and I'm heading for that ridge straight ahead." In the early days, several pilots whose aircraft were on fire ejected over the target and were either killed or taken prisoner. There had been incidents in the Thud's checkered past when a burning aircraft had exploded before the pilot could eject, but many others had flown for a considerable time without blowing up. Many pilots, like Tullo, had decided to take their chances staying with their aircraft as long as they could, rather than eject in the target area.

The ridge was still well ahead of the aircraft. The flight had climbed some but was still very low and being shot at from all quarters. Tullo's aircraft dropped its nose slightly. He pulled back on the stick. No response. He pulled harder. Still nothing. When he heard muffled explosions in the rear of the aircraft, Tullo hit the mike button: "I've gotta go, Lead. I'm losing controls. It's not responding." At 200 feet, there was no time to wait. If the aircraft nosed down, physics would be against him. Even if he managed to eject, he would likely bounce just behind the aircraft, still in the seat. He pulled up the armrests, which jettisoned the canopy, locked his elbows in the proper position, and revealed the trigger that fired the seat.

The results were the most horrific Tullo had ever experienced. At the speed he was moving, the noise, the roar, the buffeting--it was unbelievable. Everything not bolted down in the cockpit went flying past his face. He froze for a matter of seconds before he squeezed the trigger to fire the seat.

The ejection process that followed was so violent that today Tullo's memory is blank of everything that happened immediately after he squeezed the trigger. He doesn't remember leaving the cockpit, the seat separating, or the chute opening. He had the low-level lanyard hooked, which attached the parachute directly to the seat and caused it to deploy almost immediately. After tumbling violently, whomp! he was swinging in the chute.

A little battered by the violent ejection, Tullo prepared for the landing. Floating down in the chute was serene and the soft rush of air soothed him. He did not see his aircraft crash. During his descent, he eyed the city of Hanoi about 25 miles away. A small U-shaped farmhouse sat near a clearing, just to the west. He passed below the 100-foot treetops and landed in an area of 10-foot elephant grass.

At that moment, listening to the sound of his flight disappearing to the southwest, the only thing in his mind was that he was on the ground in North Vietnam, armed only with a .38 Special. His first concern was to hide the billowing white parachute. Working hard to control his breathing, he stuffed the parachute under the matted grass and covered it up with dirt. After shedding his harness and survival kit, he removed the emergency radio from his vest, extended the antenna, and prepared to contact Dogwood flight. He could hear them returning, and he had to let them know he was all right.

As the flight drew closer, Tullo turned on the survival radio. Cupping his hand around the mouthpiece, he whispered: "Dogwood Lead, this is Dogwood Two." Hoz responded immediately: "Roger Two, Lead is reading you. We're going to get a fix on your position."

The flight turned toward Tullo, who had landed on a hillside west of Hanoi. He could hear heavy anti-aircraft fire to the east and see puffs of flak dancing around the flight. Within seconds, hot shrapnel began to fall around him.

"Frank, we gotta go. Fuel is getting low, and we've been ordered out of the area. We're gonna get you a chopper." Hosmer's voice dropped: "And, Frank," he said, "this may be an all-nighter."

Tullo rogered Hosmer's message and told him he was going to try to work his way higher up the slope to make the pickup easier. He had no doubt that he would be rescued.

As the sound of Dogwood flight faded to the southwest, Tullo prepared to move up the hill to a better vantage point. He decided to open the survival kit and remove useful equipment. In a normal ejection, once stabilized in the chute and prior to landing, a pilot would reach down and pull a handle on the kit's box to deploy it. It was advisable to deploy the kit prior to landing to avoid possible leg injuries, since the case was hard and fairly heavy. Tullo hadn't had this option because he had ejected at such a low level.

He rotated the kit's red handle, and with a great whooshing roar, a dinghy began to inflate.

The dinghy! He had forgotten all about that! And it was bright yellow! He had to stop the noise. Tullo drew a large survival knife he wore strapped to the leg of his G-suit, threw himself on the dinghy, and began stabbing it. The first two blows merely rebounded. With a final mighty effort, he plunged the knife into the rubber and cut a large hole so the air could escape. With that emergency solved, Tullo lay back to catch his breath and get a drink of water. Then he started up the hill.

The elephant grass was so dense that at times he couldn't separate it with his hands and had to climb over the tough, wide blades. After climbing about 50 to 75 feet, he realized he wasn't going to make it to the top. His flightsuit was soaked, and his hands were cut by the sharp edges of the grass. Rather than waste more energy, he flattened out a small space in the grass and faced southeast to have a good view of any threat coming up the slope. Time to set up housekeeping.

Tullo's survival vest and kit included a spare battery for the radio, emergency beeper, day and night flares, pen flares, six rounds of tracer ammo, a "blood chit" printed in several languages that promised rewards for assisting downed American airmen, gold bars for buying freedom, maps, a first aid kit, water purification tablets, two tins of water, two packets of high-energy food, tape, string, 250 feet of rappeling line, a saw, knife, compass, shark repellent, fishing kit, whistle, signalling mirror, sewing kit, and two prophylactics for keeping ammunition or other equipment clean and dry. He extracted the ball ammo from his .38, loaded the tracers, and stuffed everything not immediately useful into the knapsack-type pouch. Then he sat back, tried to relax, and waited for the rescuers he knew would come.

Tullo heard the sound of prop-driven aircraft approaching from the north. He correctly assumed they were Douglas A-1s, or "Spads," as they were called. He stood up and keyed his radio. "This is Dogwood Two, do you read me?"

"Dogwood Two, this is Canasta, and we read you loud and clear. Transmit for bearing." Tullo warned Canasta of the flak to the east, and as advertised, the guns opened up as the aircraft approached Tullo's position. As soon as Tullo could see the aircraft, he began giving vectors. On the second circle, Tullo was looking right up the wing of Canasta, a flight of two Navy A1-Hs. He called, "Canasta, I'm right off your wingtip now." Canasta Lead said, "Gotcha! Don't worry, we're going for a chopper." As the Spads droned out of the area, Tullo felt sure he would be picked up.

Within a few minutes, he heard the unmistakable sound of Thuds. Thinking it could be Hosmer again, he turned on the survival radio and called, "Any F-105 over Vietnam, this is Dogwood Two." An answer came from a flight of two Thuds, which approached his position in a wide sweeping turn from the north. The flight Lead, whose voice Tullo recognized, asked Tullo to pop a smoke flare for location.

"Smoke?" Tullo replied. "Are you out of your mind? There's no way I'm going to pop smoke here!"

The pilot told Tullo to calm down. He had just spotted trucks unloading troops to the south of Tullo's position. He also reassured Tullo that they were working on getting a helicopter to him.

Tullo heard shots. They built to a crescendo, then stopped. The shooting had started at some distance but had grown closer. Soon he was able to hear voices as the troops worked their way up the hillside. He burrowed into the dense grass and waited, his heart pounding. He raised his head and saw an older man about 150 to 175 feet away wearing a cone-shaped straw hat. It was all Tullo could do not to make a run for it, but that was exactly what they wanted him to do. He forced himself to sit quietly. The troops made a lot of noise but they kept moving to the east, down the hill. Silence returned and Tullo continued to wait.

George Martin was flying his Sikorsky CH-3C helicopter to Lima 36, a remote staging area in Laos about 120 miles from Hanoi, to prepare for another day of rescue alert duty. Only a few weeks before he had been flying cargo support at Eglin Air Force Base in Florida. Today, he was commanding a small detachment of men and helicopters on a 120-day assignment in Vietnam. He and his crew had been tasked to learn a new mission for which they had little preparation.

In 1965, as the number of U.S. airstrikes and reconnaissance missions in Vietnam multiplied, pilots faced the increasing possibility of being downed deep inside Laos or North Vietnam. Crews flying the small and slow Kaman HH-43 Huskie, originally designed as an air-base firefighting and rescue helicopter, were already pushing the aircraft to its limits. There was clearly a need for a faster rescue helicopter with longer legs. The cargo-carrying CH-3C fit the bill, and the Air Force began sending crews from Eglin for specialized training. The crews practiced mountain flying, ground survival, and rescue operations, which involved coordination with controller and escort aircraft. The training was projected to last several months, but the escalating conflict wouldn't wait.

Martin, who was too close to retirement to be selected for the additional training and the accompanying extended tour, was ordered to fill in with 21 men and two CH-3s until the fully trained crews arrived. "I found out Friday afternoon and was gone Sunday evening," Martin says. "It was just like in the movies--I said, 'When do I leave?' They said, 'How fast can you pack?' "

Martin was about to land at an intermediate refueling base when he was asked by radio to divert and try to rescue a downed F-105 pilot. Martin still needed to proceed to Lima 36 to drop off cargo and extra crew. He had to lighten his aircraft to take on as much fuel as possible and still be able to pick up the pilot. "The big consideration in helicopter pickup is gross weight," Martin says. "If you're too heavy to hover, all you can do is fly around and wave at him."

Upon landing at 36, Martin's number two engine warning lights indicated an "overtemp" condition, which meant significant problems, possibly foreign object damage or a compressor stall from air starvation, and under normal circumstances would have grounded the aircraft. The crew looked to Martin for a decision. "Everybody was pretty apprehensive. I told them, 'We're his only hope. If the engine will start again after cool-down, we'll go.' " His crew reluctantly agreed.

The engine restarted without incident and Martin's CH-3, call sign "Jolly Green One," took off for Hanoi. Martin had no idea where to locate the downed pilot. He was unescorted until he was about 50 miles from Hanoi, at which point he was joined by Canasta flight, flown by Ed Greathouse and Holt Livesay from USS Midway's Attack Squadron 25.

The oppressive heat of the afternoon wore on. Finally, Tullo heard the sound of prop-driven aircraft again. Darkness was about 40 minutes away as he turned on his radio. The aircraft responded immediately. "Dogwood Two, this is Canasta. I have a chopper for you." Seconds later, Canasta flight flew directly over Tullo's position, and there, not far behind, came a helicopter. Tullo was expecting a small chopper, but this one was a big green monster, Martin's Jolly Green, the first in the theater and headed for its first combat recovery--Frank Tullo.

"Dogwood Two, this is Jolly Green. How'm I doing?" Martin said to the man on the ground. He was coming right up the valley from the south-southwest. Tullo said, "You're doing great!" and popped his pen and smoke flares. The chopper's blades made the smoke swirl as Tullo aimed his .38 straight up and fired all six tracer rounds. Crew chief Curtis Pert spotted the pilot through the thick ground cover as soon as the smoke made its way above the trees. As Martin hovered, Pert lowered a "horse collar" sling.

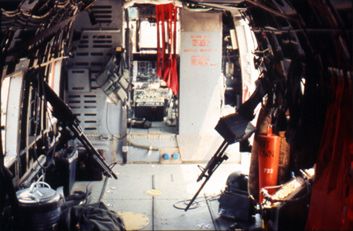

Later, better equipped rescue crews would have a specialized hoist attached to a "jungle penetrator" designed to pierce thick tree canopies. "We just had a jury-rigged cargo winch that you could turn into a 10-cent, Mickey Mouse rescue hoist," Martin says.

On the ground, the downblast was tremendous. Debris flew everywhere, and the trees and grass were whipping and bending wildly. Tullo holstered his pistol, slung the survival kit over his shoulder, and slipped the horse collar over his head. He gave the crew chief in the door a thumbs-up.

The cable became taut and Tullo began to rise off the ground. After being lifted about 10 feet, the hoist jammed and the cable stopped. The crew chief was giving hand signals Tullo did not understand. Tullo looked up. Pert and pararescueman George Thayer were in the door lowering a rope. The horse collar was cutting off the circulation in Tullo's arms and he was tiring, but he grabbed the rope and tied it around the top of the horse collar.

Finally the chopper began to move and dragged Tullo through some bushes. Everybody's trying to kill me, he thought. The Jolly climbed and circled as Pert Thayer struggled with the hoist. The overworked number two engine had begun to overheat and a fire light came on in the Jolly's cockpit. As they circled, Martin hoped that the air flowing through the engine would cool it down and the light might extinguish.

Pert and Thayer were joined by copilot Orville Keese, and the three men strained to pull the dangling man aboard. The pain was becoming so great that Tullo was thinking about dropping from the sling.

Martin spotted a rice paddy next to a house and lowered Tullo to the ground. The exhausted pilot rolled out of the sling as the chopper swung away and landed 50 or 60 feet away from him. Pert and Thayer frantically shouted to Tullo, who sprinted and dove through the door. He could hear an automatic weapon firing and saw both pilots in the helo ducking their heads.

The Jolly had problems: low fuel, a sick engine, darkness, and clouds at altitude. Martin and his crew had been in the war zone slightly more than two weeks and did not even have maps of the area. The crew relied on flares lit inside 55-gallon drums at Lima 36 and the landing lights of hovering helos to find a place to land. "We held only about a quarter of the area around the site," Martin says. "That was the only corridor you could fly through without getting shot at, because the Pathet Lao held the other three-quarters." Martin finally landed with a shaken pilot and just 750 pounds of fuel aboard.

Tullo learned his aircraft was one of six Thuds and one EB-66 electronic countermeasures aircraft shot down that day. Of three surviving pilots, Tullo was the only one rescued--the others were to spend more than seven years as POWs. Tullo returned to a Thunderchief cockpit and completed his tour. His story was later told in Thunder From Above by John Morocco.

Tullo's rescue was the farthest north that a successful pickup had been made, thanks to the determination of Martin and his crew and the long range of their CH-3C. It was the first of 1,490 recoveries that Jolly Green Giants would make in Southeast Asia. Soon a dedicated air rescue version would be built, the HH-3C, with in-flight refueling capability, armor plating, a powerful hoist, and shatterproof canopies. However, the Jolly Green Giant would find its ultimate form in the HH-53 Super Jolly, an even larger and more powerful helicopter still flown in various versions today. The technology improved, but rescue crews still had to meet the same basic requirements: a willingness to fly into hostile territory, hover in a big green target, and find a man whose only hope arrived on a cable and sling.