Two Days in the Life of a B-24 Crew

Take a fantasy flight in a real, live Liberator

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/JJ11-Two-Days-in-The-Life-of-a-B24-crew-1-FLASH.jpg)

Try not to show it’s your first mission on a B-24. As the aircraft banks into a bomb run, .50-caliber waist guns jackhammer the air with bursts of defensive fire. The bomb bay doors growl open, and the fuselage is filled with hot wind and exhaust fumes. On one of the bombs, someone has scrawled a greeting to “Adolph.” A huge cross mark has been mowed into a hay field below and covered with hundreds of pounds of puff-producing white flour.

Welcome to World War II Bomber Crew Fantasy Camp. Don’t get stuck in the ball turret. Or call sergeants “sir.”

The camp is sponsored by the Collings Foundation, a group known for preserving and flying vintage aircraft, and the 2010 session drew 12 “cadets” willing to pay nearly $4,000 each to experience two days as B-24 airmen. On its Wings of Freedom tours, Collings offers glimpses of air combat with fly-alongs in its renowned warbird collection. Fantasy Camp, however, turns toe-dipping into total immersion.

“It’s a vision I’d had since grade school,” says Taigh Ramey, president of the nonprofit Stockton Field Aviation Museum in California. Ramey, who owns Vintage Aircraft, a company specializing in the restoration of warbirds and antique aircraft, provided radios for Collings’ fleet, then expanded into piloting the classic airplanes. Four years ago, he presented his idea to foundation executive director Rob Collings: “I said, ‘Hey Rob, could we, uh, drop bombs out of your planes and shoot the guns?’ Rob thought for a minute and said, ‘I don’t see why not.’ ”

There were a number of reasons why not. “You’re taking an historic airplane, restored to look authentic, and making it into an aircraft capable of doing everything it did in World War II—not just looking like it could,” says Collings. The period-faithful had to be made 21st century functional. Ramey and about 10 volunteers from the Stockton Field museum had to reactivate inoperative bomb racks and rewire gun turrets. To support .50-caliber machine guns that actually fired (rented from suppliers to Hollywood studios), they reinforced gun mounts.

Locating a target range appropriate for the cement bombs was also an issue. Luckily, Stockton Field museum vice president Ken Terpstra has friends with large, private ranches. One friend made his ranch available for the bombing runs; another for a gunnery range.

Paying participants started booking in 2009, and, despite the moribund economy, last year’s camp had one more camper than the 2009 session.

DAY ONE, 7 A.M. In the lobby of a Holiday Inn, a pair of uniformed U.S. Army Air Forces non-coms—1940s-correct down to glasses and wristwatches—bark out a roster of names. Guests at the continental breakfast bar gape as the olive-drab cadre boards a bus bound for the training school at Stockton Army Air Field (better known as Stockton Metropolitan Airport).

Brothers Chris and Craig Connor from Long Island, New York, are on the bus. Craig is a U.S. Air National Guard flight engineer on Lockheed C-130s. Both brothers are hardcore World War II buffs and collectors. “To experience even a minuscule cross-section of what bomber crews endured during the war is going to be incredible,” Craig tells me. “That’s why we’re here.”

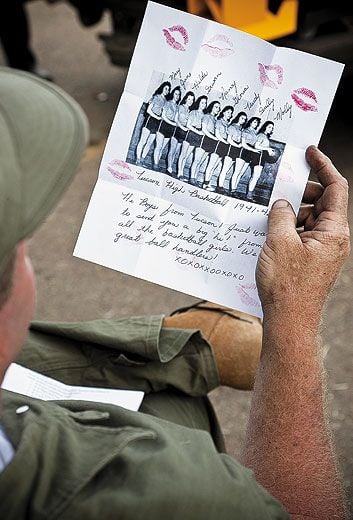

In the shadow of the Stockton control tower, Ramey and the volunteers have transformed the Stockton Field museum’s 1970s prefab hangar into a World War II barracks. Bunks and footlockers line one wall. Belts of .50-caliber ammo overflow stenciled wood crates. A lounging re-enactor reads circa-1940s magazines. On the walls are posted orders in the jittery font of manual typewriters, and the mock mail from home bears three-cent victory stamps.

Out in the parking lot, the vibe is decidedly pre-New Army. “Get this through your thick skulls,” roars a sweating sergeant named Murphy at campers standing at attention (sort of). “See these stripes? I actually work for a living. I am not a ‘sir.’ ”

A 60-year old ex-Marine, Tim Murphy is one of about 10 volunteer re-enactors populating the illusion. Most are members of the Arizona Ground Crew Living History Unit, based in Phoenix. Genial and low-key behind the scenes, Murphy describes their mission simply: “Folks come here wanting to be immersed in World War II. Well, we’re gonna drown you.” He plays the part like a B-movie character actor, bellowing and blustering, venting harangue and sly humor. All part of the make-believe, sure. But when Sergeant Murphy gets in your face, you wipe off that grin and shape up.

Jamie Stowell is the sole female camper. A power grid controller from Sacramento, she’s already drawn the nickname “Miss Roosevelt” from Murphy. (“You gotta be related to the president, ’cause I don’t know how you got into the Army Air Corps otherwise.”) Actually, Stowell’s father trained in B-24s before requesting a transfer to the North American B-25. During combat in Europe, he was a B-25 aircraft commander. Stowell is here as a tribute to his service. “I think it’s going to be really cool to get in the turrets and see what my father went through,” she says.

In the role of ranking officer, Captain Bill Gaston, another Arizona re-enactor, wears a flat-brimmed campaign hat and khakis with razor creases. He remains meticulously in character at all times, ordering us about in clipped, unsmiling sentences. After a faded Army filmstrip on venereal disease prevention—“Mandatory!” he snaps—a half-day cram course begins.

Navigation, armament, and bomb delivery, along with real-life hardware, are fast-tracked through show and tell. Instructor credentials are impressive: Jim Goolsby, one of the pilots of the Collings B-24, teaches navigation and radios. A retired United Airlines 747 captain, Goolsby began as a commercial airline navigator on Boeing 707s.

Parked a hundred yards from fantasy camp is a Consolidated B-24J Liberator named Witchcraft, in honor of a European-theater bomber that flew 130 missions with the Eighth Air Force. Built in 1944, our bomber flew with the Royal Air Force under the Lend-Lease Act. Later, in the Pacific, it pulled anti-sub patrol on missions lasting more than 20 hours. Then and now, Boeing’s B-17 got the glamour. But the four-engine B-24 was the Big War workhorse, shouldering more tonnage than any other bomber in the U.S. fleet.

MO LEVICH is a jazz trumpeter and director of a Bay Area big band that has performed for years beneath the wings of Collings Foundation bombers at airshows. That’s no coincidence: Levich’s home library is devoted entirely to World War II history. “I’ve studied this stuff since I was five or six years old,” he tells me during a break from class instruction. But his hitch at B-24 camp results from deeper gravitational forces. “I was pulled here because of my background,” he says. A few members of Levich’s family, Polish Jews, got out of Europe after Germany was defeated. “All I can do now is come here and honor the guys who flew these airplanes,” he says. “Because if they hadn’t prevailed then, I wouldn’t be here today.”

Levich and the other cadets assemble in the hangar-turned-classroom. “Turn off the cameras,” says Taigh Ramey, “and close the doors.” The Norden bombsight is unveiled. Though its mythology overshadows its real-world accuracy, the Norden was one of the war’s most guarded secrets. It’s a mechanical brain with hundreds of moving parts, capable of steering the course to the target and computing the bomb release point. A bombsight historian and collector, Ramey fills the chalkboard with diagrams depicting drift angle, track, and wind speed. In case we’re forced down, he passes around once-classified documentation showing precisely where to shoot a Norden with a .45 pistol to make it unusable to the enemy.

1 p.m. Lunch under a camp canopy on a sun-bleached ranch. The baloney sandwich buffet is from a World War II Army recipe book, and the food is served in mess tins.

After lunch, we make our way to a makeshift gunnery range to perforate paper airplanes with everything from machine guns to handguns. A 1942 Chevy turret trainer truck rests in a patch of shade. Using a shotgun mounted inside the powered turret, campers learn aerial targeting. Clay pigeons simulate attacking fighters.

Rob Collings arrived in Stockton piloting the P-51 Mustang Betty Jane. As a multi-caliber salvo erupts, he describes how the Collings Foundation’s philosophy shaped the camp. “Our whole mission is living history,” he says. “The airplane rides have been one part of it. Now we want to get more of that experience across. We can’t show campers all the hardships of war, certainly, but we can show them the training and what people had to go through on a daily basis.”

The logistics are daunting. “Especially when you want to shoot machine guns,” says Collings. “There are lots of places where you just can’t do that.”

“I’m not a gun nut,” Jamie Stowell assures me after her turn at the thundering .50-caliber. “But oh my God! It’s just astonishing power.” Nothing like the rat-tat rattle of movie machine guns, the fire-spitting Browning quakes the air and even the ground beneath your feet.

Over at the training turret, clay pigeons maintain air superiority. Few 21st century skills are transferable to sitting in a rotating turret while simultaneously adjusting gun elevation and manually tracking an unfriendly in three dimensions. Craig Connor respects the lower-tech ethos of 1944. After climbing down from the turret, he says: “In World War II, the human aspect of a bomber crew, the interaction between those guys, was everything. Now black boxes tell you where to go and what to do. Technology just takes people further and further out of the picture.”

Recoil bruises, intense sunlight, and the umpteenth .50-caliber cartridge jam eventually sap campers’ trigger-happiness. Back in Stockton, the 12-hour day ends with re-enactors reading aloud fake letters from home. “You may return to your billet,” Captain Gaston commands, “and fall unconscious.”

DAY TWO, 7 A.M. Above Witchcraft, an American flag flutters in clear morning light. As Jim Goolsby conducts a walk-through of the B-24, he exudes more tough love than romanticism. Mo Levich inquires about the big bomber’s glide ratio; “A little better than a brick,” he replies bluntly.

Up narrow steps, the flight deck is a museum of war production ergonomics: banks of dials and toggles flanked by handles and levers. Control of the bomber’s large flight surfaces is unassisted by hydraulics. “They’re a little heavier than what you’re used to in a Cessna,” Goolsby tells Levich as we test the action. Rudders have the pedal travel of an elliptical trainer at the gym. Pulling the control wheel back to its limit, you feel every foot of greased cable winding through pulleys and stretching back to the big elevators.

How do today’s pilots relate to Witchcraft’s fly-by-might controls and primitive cockpit environment? “We get jet jockeys in here all the time,” says Goolsby, “and they do a terrible job. We’ve also had people who fly for the airlines train to fly it and they’ll tell you, this ain’t anything like an airliner.”

Re-enactor Sergeant Ken Terpstra, of the Stockton Field museum, has World War II bomber nose art tattooed on his right arm, so I’m not surprised when he says, “I should have been born a long time ago.” A San Joaquin County deputy sheriff, he stands atop the ball turret trainer, psyching up volunteers to squeeze into the metal orb with the plexiglass porthole. Not everyone wants to—or can. After training in basic rotation and target tracking, Terpstra instructs aspirants to signal him in case of sudden claustrophobia and/or vertigo. “I’ll get you out of there quick,” he promises.

Mid-morning lethargy is staved off by loading 220-pound cement bombs into Witchcraft’s bay. Oil must be purged from engine cylinders too. “I’ll do the freakin’ counting for you,” Sergeant Murphy shouts as we manually push the enormous props through a prescribed number of revolutions.

1 p.m. Captain Gaston delivers the briefing. There will be two 80-minute flights, each carrying a six-camper crew. Our target is in a hay field on a private ranch east of Stockton.

Board the B-24 through the bomb bay (unless you’re one of the uninitiated). Inside, Ken Terpstra encourages us to “get the whole experience.” He grants us free rein, only warning us that after the bomb doors open at altitude, we shouldn’t stroll along the 12-inch-wide bomb bay catwalk. (Strike that off the bucket list.)

Four aircraft with a combined age of more than 250 years make a time-tripping lineup on the Stockton taxiway. Vintage Aircraft’s Twin Beech is a camera aircraft (an opportunity to shoot a B-24 dropping bombs and firing machine guns attracts major photog talent), and a Stinson L-5 will scout the target. We can expect opposition, but not—as we’d hoped—the Collings’ Messerschmitt Me 262 (it’s grounded). Instead, Rob Collings will pilot the P-51.

Witchcraft’s takeoff roll seems interminable. But the climbout with all 56 cylinders hammering—that big wing banking in the sun—is glorious. Long before cruising altitude, seat belts click off. One camper is already walking toward the rear gun position. I’m crawling through a duct-like tunnel beneath the cockpit into the nose.

What airplane buff hasn’t imagined how it must have been in the war, perched up front in a glass bubble, plowing through blue sky with the might of a bomber roaring at your back? This flight is just like it was, without the deadly flak. Below, in the bombardier’s compartment, Taigh Ramey lets me peer into the Norden bombsight. The crosshairs drift across a turquoise swimming pool, then a small-town mini-mall. I imagine people looking up.

Over the ranch, reports from a .50-caliber percuss the fuselage. Mo Levich is alternating single shots with staccato bursts—okay, they’re blanks—out the waist-gun port, leaning into the recoil as he tracks a target at 10 o’clock low. Due to mechanical problems, the P-51 has returned to base, so we’re targeting the camera aircraft instead. No aggro Mustang, the docile Beech is easier to track than a clay pigeon.

Chris Connor is manning the ball turret, pulling 360-degree rotations and inclining the guns vertically. Fantasize this: You’re crammed inside a Christmas ornament suspended from the bomber’s belly while arcing Bf 109s fire 20-mm cannon at you.

We’ve banked repeatedly, dropping altitude in increments. Now we level into an arrow-straight path, with only slight deviations. Up in the bombardier’s compartment, Ramey feeds corrections to the cockpit as the Norden figures the path and calculates the release point. The bomb bay bell jangles, and doors retract. Nearly a quarter-ton of cement heads for the target.

After two more bombing runs (no plume of flour noted), we head for base. After we land, mission two, hauling six more campers, departs. A second P-51 is scrambled to serve as a target stand-in.

When everyone’s back on the ground, there’s a graduation ceremony outside the Stockton Field museum’s hangar. Ribbons are awarded at attention and the class guidon retired. Sergeant Murphy, in full dress uniform, barks his final order: “Dismissed for chow and inebriation.”

Later, the campers enjoy cold beers and grilled steaks. Tim Murphy is wearing a flowered shirt. Bill Gaston is smiling. Jamie Stowell now knows something of her father’s experience “and the astonishing level of courage it took to do it.”

Craig Connor leaves with a connection to his own service in C-130s: “Could we follow in those guys’ footsteps? I don’t think so. But the crew camaraderie and the mission—all of that still exists today. I’ll be back on duty Tuesday.”

Mo Levich’s years of research have a first-hand dimension now. “For me, there’s no more imagining what those men did for us and what we owe them. We owe them....” His voice trails off and he shakes his head. “I can’t fill in the rest.”

As the class of 2010 checks out of Fantasy Camp, reality looms in the silent silhouette of a B-24 in the day’s fading twilight, and the spirit of those who flew it 65 years ago.

Stephen Joiner is a frequent Air & Space/Smithsonian contributor.