The Fighting Drones of Ukraine

In garages and warehouses around Kiev, an army of gadgeteers takes on the Russian war machine.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7f/b4/7fb4236a-8109-40ff-869c-db5a086f12d3/08b_fm2018_62_pisky_frontline_wendle_main_img_2279_live.jpg)

The buzz of a drone cuts over the dark green treetops toward the rebel checkpoint, a ramshackle heap of concrete blocks and torn camouflage netting on the edge of Donetsk, the biggest city in rebel-controlled eastern Ukraine. The road is pitted with shallow mortar craters. Power lines hang limply from their poles. As we slow down to avoid a pine trunk that’s been dragged across the road as a makeshift barricade, a separatist steps out from the cement bunker and swings his Kalashnikov in our direction. Then he looks up at the octocopter hovering overhead—and flips it off. “They’re always watching us,” he says. “And we’re always watching them.”

That was the situation in September 2014, six months after Russia annexed Crimea. News of the war in Ukraine traveled around the world just as uncrewed aerial vehicles (UAVs) were becoming widely available, even in a combat zone. Today, fueled in part by Soviet-era technological know-how, the skies over eastern Ukraine are alive with pilotless 21st century air power winging over a shredded landscape of World War I-style trenches and Soviet artillery.

When the war started, in 2014, the Ukrainian army was the second biggest in Europe, but it did not have a single modern UAV. Arrayed against Ukrainian government forces was a Russian military that was modernizing itself and backing a rebel force in eastern Ukraine. The Kremlin was embracing asymmetric tactics ranging from false flag operations to cyber warfare. Ukraine had an army of conscripts withered by a quarter-century of corruption and funding shortages.

In the intervening four years, the conflict has only grown deadlier. The civil war that began when some residents of Ukraine’s heavily industrial Donbass region rebelled in support of Russia has now killed more than 10,000 people, about 30 percent of them civilians, the Guardian reported in late 2017. The 2015 Minsk Agreement between Kiev and Moscow was supposed to create a cease fire and a plan to reintegrate Ukraine’s separatist regions, with new elections in the rebel-held territories to follow. None of that has come to pass.

In Avdiivka, a town near the frontline dividing Ukraine’s government-controlled territory from what the separatists have renamed the People’s Republic of Donetsk, seemingly peaceful days are still shattered without warning by incoming artillery shells. And the United Nations says that anti-vehicle land mines killed more people in Ukraine in 2016 than in any other country in the world.

While the prospects for peace remain bleak, Ukraine has managed to punch above its military weight in the conflict by turning to its world-renowned aeronautics industry. Unique to this war is a new group of volunteer tinkerers building do-it-yourself UAVs.

As the fighting in Ukraine continues to kill people almost daily, the battle space has become much more complex, pressuring basement gadgeteers to become increasingly innovative. They have begun to develop combat drones and tactics that surpass those found elsewhere in the world.

Lieutenant Colonel Ty Shepard, a U.S. Army National Guardsman advising the Delta Center—a Ukrainian military command and control program—says the Ukrainians have been quick to adapt to the new battlefield. “In the last two years since this organization has been set up, they’ve rapidly advanced from using dirigibles or balloons to do reconnaissance to building their own UAV systems,” he says. “And that’s from zero.”

Delta, staffed by about 40 specially selected graduates from Ukrainian military academies, is working to decrease the time it takes for information collected by drones and CCTVs to reach the Ukrainian General Staff, increasing real-time awareness of the situation on the frontline. Some of this intelligence is also shared with U.S. military attachés, who are analyzing it to better understand Russia’s capabilities.

Shepard is posted with the Defense Education Advisory Group, part of the U.S. Embassy’s Office of Defense Cooperation in Kiev. He’s impressed with the expertise in Ukraine’s drone-building community. “They’re constantly thinking of different techniques from the UAV side,” he says. “The smaller UAVs—some of their capabilities are better than ours.” He describes the soldiers working for the Delta Center as “the ultimate geek squad.”

THE BRAINS OF UKRAINE

“Ukraine’s main competence is our brains,” says Dennis Gurak, deputy director for foreign investment at UkrOboronProm, the state-owned defense company. “Math, physics, and engineering are our key capabilities.” Gurak has a background in international management and marketing.

Now he is promoting a resurgence of the Ukrainian defense industry—formerly a key component of the Russian economy. Until the war broke out, many key components in Russian military hardware—from tanks and rockets to helicopters and missiles—had been manufactured in Ukraine. “If you compare our capabilities with Russia,” says Gurak, “we are 100 percent competitors with them basically in all fields of technology, especially in the defense industry.”

Munching on a croissant in a French cafe in downtown Kiev, he says the defense sector is so expansive he thinks of it as a country within a country. “Drones are quite a good example,” he says. “I don’t know of any other country in the world—except probably the U.S. or China—which would be able to start its own drone industry in two years.”

Now, traditional defense industries—aircraft, armor, munitions building—have foundered in Ukraine, while the new industry of drone manufacturing has flourished. This is due to its reliance on key strengths like computer programming and engineering, which do not require heavy industrial equipment, and because of low startup costs.

Human capital is abundant here. Ukraine’s four specialized aerospace universities graduate about 10,000 IT specialists each year, as many as half of whom eventually leave the country in their search for employment. (Last November, an analyst from the Ukrainian think tank CEDOS told UNIAN, a Kiev-based news agency, that Ukraine’s Ministry of Education is reluctant to track the employment status of Ukraine’s higher-ed graduates because they know that the percentage of grads who leave the country and/or take jobs that do not require an advanced degree would embarrass the nation.)

THE GIFT OF SIGHT

In the spring of 2014, Ukrainian IT graduates found a new job opportunity. Across the Donbass, the coal mining belt and industrial heartland in southeast Ukraine, militias were arming and road blocks manned by angry miners were springing up. As Russian arms, ammunition, equipment, and troops flooded the region, the Ukrainian army was thrown back again and again.

Seeing that the army was basically blind, model airplane hobbyists, newbie commercial drone pilots, and kitchen table inventors headed to their garages and began building UAVs to give sight to the defenders of the motherland.

One of those groups, Matrix UAV, has advanced from the garage into a dilapidated Soviet industrial park. Across a lot filled with delivery vans, the entrance to Matrix UAV is wide open. The menacing rocket tubes of a drone dubbed the Commander point out the door.

I walk into the room housing Matrix’s centerpiece of aerial warfare and no one notices. From a darkened hallway I hear voices. The room they guide me to is a tinkerer’s paradise: A giant table is littered with mini rotors, circuit boards, pliers, fuselages, wires, and a small racing drone. Smiling from the walls of the workshop are several photographs of Rudolf Kálmán, an American electrical engineer who invented an algorithm widely used in the guidance systems of everything from the U.S. space shuttles to drones.

The designers finally look up from their soldering equipment and the design programs on their computers. Yuri Kasyanov, the gaunt founder of Matrix, comes over, grips my hand, and accuses me of being a spy.

I manage an awkward laugh, and then he walks me back to show off the Commander.

As we enter, Andrei Puliaev returns from the kitchen with a mug of tea. The Commander is his brainchild. Though the rest of the team are mostly 20-somethings crammed into the chaotic open workshop, Puliaev, 50, has a space that is organized and quiet. He’s from a rebel-held town near the frontline. His elderly parents still live there. Unlike Kasyanov, who graduated from a Soviet military aviation academy, Puliaev was drafted by the Red Army. Then he passed on a chance to study aviation engineering in Siberia. It was too far from his family.

From childhood, he was passionate about helicopters. As a youth, he joined an aviation design club and traveled all over the Soviet Union, winning design competitions in East Germany and the Baltics. At 19, he designed and built a fully functional helicopter. Then the Soviet Union collapsed, and the opportunities ended. Before the war started, he worked near Donetsk, hacking and repairing the computers in the Mercedes sedans of the city’s mafia elite. Now, after a quarter-century’s interruption, he is back doing what he loves. “Here,” he says, as he cranks down on an aircraft-grade aluminum bracket, “I can incarnate any fantasy.”

Well, maybe not any fantasy. The Commander’s spindly aluminum scaffold holds rocket tubes, a GPS guidance system, and a gas engine that powers 10 rotors, collectively roaring at the pitch of a motorcycle. Puliaev wants to build an even larger version that would be able to transport wounded soldiers, deliver blood to the battlefield, or put out fires. “But America will not sell us big engines,” says Kasyanov. He points out motors with Chinese writing on them; the gadgeteers have to buy low-quality Chinese components, or make their own.

“Many of the governments of Western countries—the United States, Germany, France, and other countries—they do not want to sell any powerful engines to Ukraine, because we are at war and they do not want to quarrel with Putin,” says Kasyanov.

This inability to buy top-grade components is holding Ukraine back, according to Beatrice Bernardi, a senior aviation analyst and UAV expert for IHS Jane’s, a military analysis firm. The Ukrainians “are doing pretty well with what they have,” she says. “But Ukrainian drones are not particularly developed in terms of weaponry. It’s mainly a surveillance capability.”

Kasyanov is unbowed. “We do not need the Minsk [ceasefire agreement] to win the war, we need a hundred machines like this”—he gestures toward the drone—“with missiles that will destroy Russian armored vehicles. Then we will easily liberate our land. If the war gets really big, then we will go to war with the Commander. And not with just one.”

ENTER THE KATANA

But Matrix’s real contribution to the fight so far is not the scary combat drone. It’s a five-foot-wide foam airplane. They have dubbed it the Katana, Japanese for “sword,” a name at odds with its white, rubbery foam body, which resembles a cartoon version of a B-2 bomber more than a Samurai weapon. Matrix mass-produces the Katana with funding from a Canadian donor. The airplane can carry several types of commercial cameras—albeit one at a time—bringing its cost to about $5,000 a pop. Matrix trains national guardsmen to fly them, and the UAVs are then donated to guard units on the frontline.

Everyone agrees there is nothing exotic about any of the UAVs being made and used today. Most tinkerers and producers base their designs on something like the RVJET, made by RangeVideo, a hobby aircraft company based in Miami, whose slogan is “Make fun, not war.” Today, Matrix’s UAVs fly over the battlefield, snapping pictures or recording video that is saved to a memory card. Because they are so small and quiet and fly at an altitude of around 300 or 400 meters (10,000 or 13,000 feet), the biggest worry is not that they will be shot down, but that the batteries will die or that the radio signal will be jammed by Russian equipment, and the craft—and its memory card—will be lost.

The Katana and similar UAVs may not be sophisticated tools, but they’re essential ones. Their operators are usually near, but behind the frontline, relying on the drones to supply intelligence on the emplacement of artillery, tanks, and rocket systems. The news they’ve been providing is grim. Since the war began, more than 10,000 soldiers and civilians have been killed on both sides, and the fighting has displaced nearly 1.6 million people.

The battlefield the drones fly over could date from the Great War. Networks of trenches stretch into the distance, protected by bunkers, minefields, tank traps, and barbed wire. Opposing positions are sometimes only a few hundred meters apart. Soviet-era machine guns clatter from shallow fighting pits. Blind shelling of residential areas on both sides of the line terrorizes and kills civilians. Hundreds of thousands of people are too poor, too sick, or too elderly to escape the front. They spend days at a time cowering from artillery barrages in damp, unheated cellars with no electricity.

Only the drones make it apparent this is the 21st century.

DRONE WARS

A battered Soviet-era tank grinds out of the tree line and heaves up over a berm in a smog of dust and exhaust, heading toward Ukrainian lines. Across the Delta Center’s wall of screens, the CCTV system shows the tank turning sharply, then driving silently.

“If you saw a tank from a U.S. position in other areas of the world, that would be a dead tank,” says Shepard, the American officer. “That’s a done deal if it was that close. But they don’t have anything up there currently at that position. No artillery. Maybe an 82mm mortar, an RPG [rocket-propelled grenade] or a recoilless rifle. They could also bring our artillery in later on and accurately pound that area to defend the ground.”

During his time at Delta, Shepard has seen the war rapidly mutate. “From the ground, it looks like trench warfare,” he says. “We’ve dug in and it’s a large-scale artillery fight and then taking and holding ground. But on the flip side…in the air as far as electronics warfare, it’s a whole different ballgame. It’s almost like Star Wars going on, where it’s constantly jamming, constantly monitoring, constantly detecting, constantly surveilling, using all these different systems.”

On this bank of screens, he’s seen it all: “Firefights between people and huge artillery barrages, tanks engaging in tank fights, UAV aerial attacks. It’s pretty exotic as far as the tactics being used here. Not just one UAV, but using formations, using multiple UAVs and doing different techniques where you’ve got essentially a wingman and different resources out there. It’s pretty interesting.”

Drones rely on GPS or radio signals to navigate, so as the Russian-backed rebels—and to a lesser extent, the Ukrainians—jam one another, a sort of signals-warfare arms race has evolved. Shepard calls the war a petri dish for innovation. “From the Russian side, they’re using [the war] as kind of a test bed for some of the tactics and techniques, which is, I guess, a good place to test them, potentially, and then taking those lessons learned and rolling them into places like Syria, and then refining them even more in those environments,” he says. At the same time, the United States—which is providing logistical support—is also observing and learning.

But the Ukrainians are fighting at a disadvantage, according to Omar Lamrani, a senior military analyst at Stratfor, a geopolitical intelligence company. He says: “I think where the weak points are and where Ukraine would either need a foreign partner or assistance, like from the United States, is in terms of the data links, the communication systems, the ability basically to fly these UAVs in a secure way, without being susceptible to jamming or loss of communication. Ukraine has been very eye-opening in terms of the UAV drone market, but also in other aspects, in terms of just how sophisticated a modern battlefield is…. The United States was surprised, to a certain extent, when they saw how advanced the Russians are with these small tactical systems and also their ability to jam them.”

Shepard asserts that both Ukrainian and Russian drones are capable of making attacks rather than merely observing, sometimes deep into enemy territory. “You’ve got ones that go out and just jam, you have ones that do surveillance, [and you have] ones that drop ordnance,” he says.

I ask if he’s certain the Ukrainians are firing or dropping ordnance from UAVs. He smiles and says: “I cannot comment on that. All I can say is they have very advanced Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures [TTPs] which greatly assist with protecting the sovereignty of their country.”

Some of these air strikes have occurred well within Ukraine’s borders, targeting ammunition dumps and bases. In September, an explosion at a military depot in the Vinnytsia region—possibly caused by a drone—cooked off 83,000 tons of ammunition, forcing the evacuation of some 30,000 people. In March, Ukrainian security services say a Russian drone dropped a ZMG-1 thermite grenade on Balakliya, a military base in eastern Ukraine, just 60 miles from the Russian border. The detonation destroyed several tons of ammunition.

SOUND AND FURY

Ukrainian UAV manufacturers are also developing “kamikaze” drones—UAVs that can wait on station for hours before being piloted into a target and blown up.

Artyem Vyunnik, one of the founding partners of Athlon Avia, disapproves of the concept. He says, “Every time I go to the [General] Staff they ask me, ‘When will you present us with this kamikaze or something like that?’ From the very beginning we did not want to do that. We didn’t want to kill people.” His company builds the Fury, a specialized spotter for heavy artillery.

Athlon Avia is housed in a two-story building attached to an apartment block in one of Kiev’s residential neighborhoods. Graffiti is sprayed across the beige exterior. There is no sign. The company next door sells South Korean massage beds.

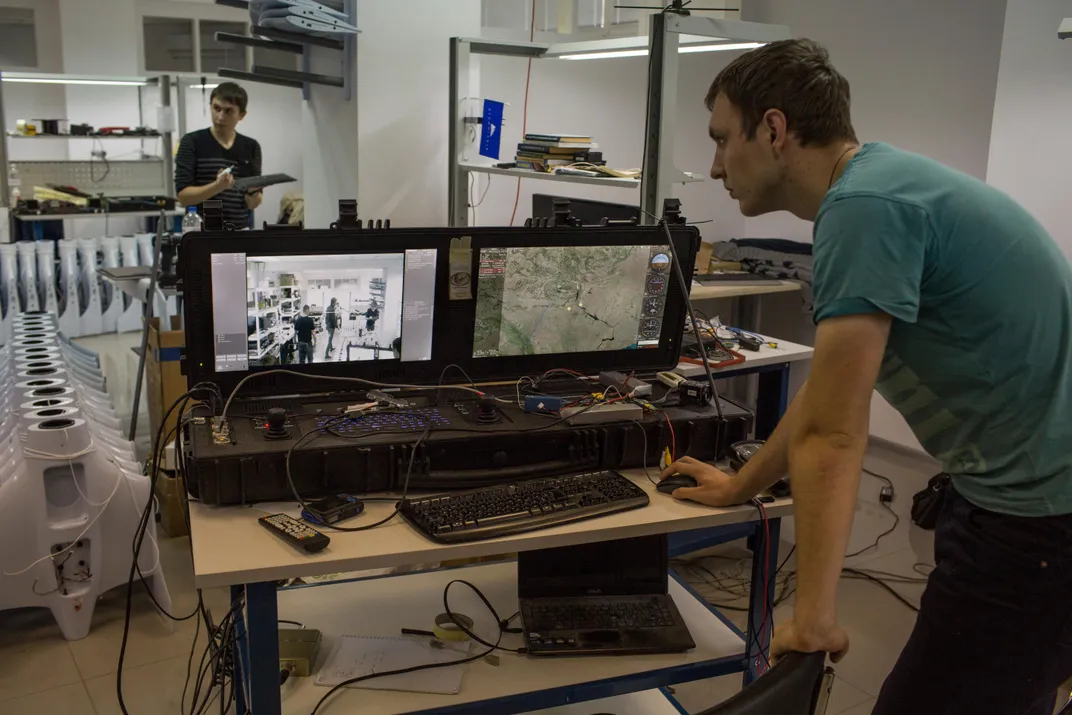

Inside, electronic music pulses from the speakers in a shiny white and gray workshop. A 21-year-old computer programmer taps away on a Fury ground console, entering code to set up the UAV’s proprietary targeting software.

Vyunnik is not an engineer or a technician; instead, he has natural business acumen. He was born in the hardscrabble eastern town of Kostyantynivka, which in Soviet times made the glass for the red stars atop the Kremlin. At 25, he was running a big company in Donetsk exporting suits to Zara and Marks & Spencer in Europe. He moved to Kiev to escape the cronyism that plagued the east and picked up a law degree on the way. He got into drones because it was fun.

Now, his hobby has been transformed into a thriving company. The army, he says, “needs everything.”

But Vyunnik and his partners were not interested in building another generic drone. Instead, they chose to make Athlon Avia the first company to specialize in artillery target correction.

“You need very specific software for artillery calculations,” Vyunnik explains. “The Soviet standard allowed for the use of 300 shells for target correction. When we use our drones, we make one shot, then a correction, and then six guns shoot and the target is destroyed. We are just improving the old type of war. We understand that. But thanks to our drones, we are more efficient.”

But while Athlon’s software is of this century, Ukraine’s frontline units are still somewhat stuck in the last. The Delta Center is supposed to collate and share information collected by the Fury with units in the field. So far, Vyunnik says, that’s not happening.

“We tried to cooperate with [Delta], but it’s not possible because we do not understand one another,” he says. “We cannot understand what their goals are. Every time we go to the testing center, guys from different units ask us if we can transfer our data to some kind of system like Delta. It can be easily transferred to everybody, to any kind of system, but nobody told me where to transfer it and how to do it. The devil is in the details.”

Details aside, the massive transformation of the Ukrainian gadgeteers of 2014 into the professional UAV manufacturers of today may foreshadow a revolution in tactical-drone production and drone tactics for smaller countries around the world.

“We never manufactured drones before 2014, and now in two and a half or three years there are companies in Ukraine which are doing military-grade drones,” says Gurak. “The capabilities of our industries have allowed [Ukraine] to actually sustain the war. It is actually a very big achievement that we were able to do this because nobody believed in us. Volunteers gave what they could give, but you can’t win the war just with human energy.”

Ukraine is showing the world that in the conflicts of the future, small powers fighting stronger opponents will use robots to fortify their human armies.