Every year between 1953 and 2019, the Experimental Aircraft Association held a convention of aviation enthusiasts, which, as readers of this magazine know, has grown into the largest, most famous celebration of private aviation in the world. In that time, the EAA has hosted some of history’s most significant aircraft—and some of its most outlandish. Burt Rutan’s world-circling Voyager and his revolutionary VariEze, the Boeing 747 on its 50th birthday, the last flying Lockheed Vega—all have basked in the adulation of audiences who know a great airplane when they see one.

For 60 years, airplane lovers the world over have made a pilgrimage in late July to Oshkosh, Wisconsin (and before 1970, to Rockford, Illinois) to what the EAA calls AirVenture but most of us know as “Oshkosh.” But not this year. Oshkosh 2020 fell victim to a pandemic that has kept many of us from our most cherished rituals, and half a million people will feel its loss. Although nothing can replace Oshkosh, we hope the voices of a few of its most loyal fans—and photographs of some of its finest moments—will provide comfort food for thought, helping those with memories of the fly-in to recall their own best times and inspiring those who have never been to dream of going next year. We hope we can all soon start saying again that most frequent of pilot farewells: “See you at Oshkosh.” — The Editors

Everybody Knows Your Name

Les Bryan has been going to Oshkosh since 1978. a former digital imaging technician at indiana’s Evansville Courier & Press, He flies a 1948 Cessna 140 from skylane airport near Evansville.

Before the Voyager flew around the world, [Dick Rutan and Jeanna Yeager] brought it to Oshkosh. When it flew over, it looked like a big “H” in the sky. When they landed, they were treated like rock stars. And their message was: “This is EAA, home to the homebuilders. This is a homebuilt and we’re gonna fly this airplane all around the world, nonstop, unrefueled.” It made me imagine what Charles Lindbergh was like when he was promoting aviation after his flight.

I’ve flown to Oshkosh so many times I don’t need a map. There’s a pool of air traffic controllers from the Great Lakes region—and from other parts of the country—and the pool has seasoned controllers, some with medium [experience], and some rookies. Some of the controllers at Oshkosh have worked the Evansville tower. They love working Oshkosh. To them, it’s fun: “How many things can you throw at me, and I can still make it work?”

I’m coming in to land one time and normally they just give you color and type: “High-wing, red-and-white Cessna, rock your wings, follow the guy in front of you, come on down.” As I’m doing that, I get a call: “Okay, Les. You’re cleared to land,” and I’m like “Oh, my God. I’ve been coming to Oshkosh way too long if the controllers can call me by my first name.” It was one of the controllers from Evansville. I’m really sad that I’m going to miss my friends this year.

People People

Since 2017, Bonnie and Craig Fitzsimmons have been wintering in Florida and spending April through mid-September in their trailer in Audrey’s Park, a residential campground on the AirVenture grounds. Craig is the chairman of the 40-plus volunteers who staff the AirVenture communications center, and Bonnie volunteers in the EAA warehouse and for the print-and-mail operation.

Bonnie: In the evening after everyone is done volunteering, they usually meet on our deck and we have a grand old time. I love meeting all the people. When we gather at night, Craig always says to me “Who’d you meet today?”

Craig: If it weren’t for the people, I don’t think we’d invest so much time in it. The communications group puts up all the speakers for the P.A. system. We take care of all 700 two-way radios they use on the grounds. We monitor the equipment in the airboss trailer where the airshow is directed. I also help the grounds maintenance guys. I guess I’m known for driving a tractor.

He puts up all 1,500 of the picnic tables for the campgrounds.

It takes us about two weeks to set out 1,500 picnic tables. One year we put in a weather warning system. That was a lot of antennas and speakers. That took us all summer to do. If you have a group of volunteers, you’ve got to have something for those folks to do, or they won’t come back.

We didn’t start out as airplane enthusiasts. People come here because they like to be around airplanes or they like to be around people or both. We are the both.

We get to fly in a lot of the airplanes. I remember once hearing my name being yelled. ‘Hey Craig! Hey Craig!’ and I turn around, and it’s my wife flying by in the Breezy [a no-cockpit homebuilt made for joy rides] with the guy who invented it, Carl Unger.

Best ever! I saw Oshkosh from a different view! It was a blast!

My EAA number is 266,725. One of the guys in our group—his number’s 156.

And he’s out there working as hard as the rest of them.

He’s 84 years old.

And you’d never know it.

You’d never know it.

For us, what stands out is the friendships we’ve made. It’s more of a gathering of great friends.

I Built This Myself

Fred Keip went to his first Oshkosh in 1974, got his license in 1975, bought the plans for his homebuilt in 1976, and in 1986, flew it to Oshkosh.

Going to Oshkosh was the fuel on the fire. John Monett’s Sonerai [a small two-seater with a Volkswagen engine] was growing in popularity, and there were really a lot of them there. Every year I’d go to Oshkosh to get fired up again. You work on it all year, off and on, but you go there and see all these finished airplanes—it gets you going for a few months more.

That’s kind of an EAA’ers ultimate goal—to take your airplane to Oshkosh. Every year, I’d go up there and talk to Sonerai builders. You might be at some particular phase in the build, and you take pictures and talk to people and say “Oh, that’s how that guy did it.” I’ve got hundreds of photographs that I took while there—I probably spent as much on film as I did on airplane parts—and then when I was building my airplane, I’d get stuck on something, I’d go to the picture box. Once I had the airplane done, I felt obligated to take mine up there every year and do a little payback.

Back in April, I was joking around with my friends and said, “If they cancel Oshkosh this year, I’m going to fly up there, land, taxi over onto the big square, get out of my airplane, take a bunch a pictures, and go back home and jump on Facebook and say, ‘Hey, where was everybody?’”

Next Gen

Connor Madison doesn’t have much of a memory of his first Oshkosh: He was four months old. Today, he’s the EAA staff photographer.

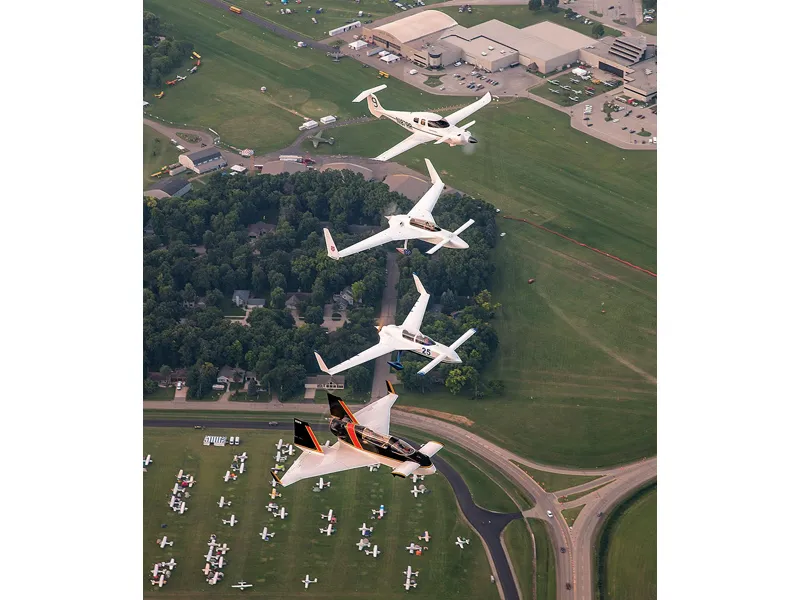

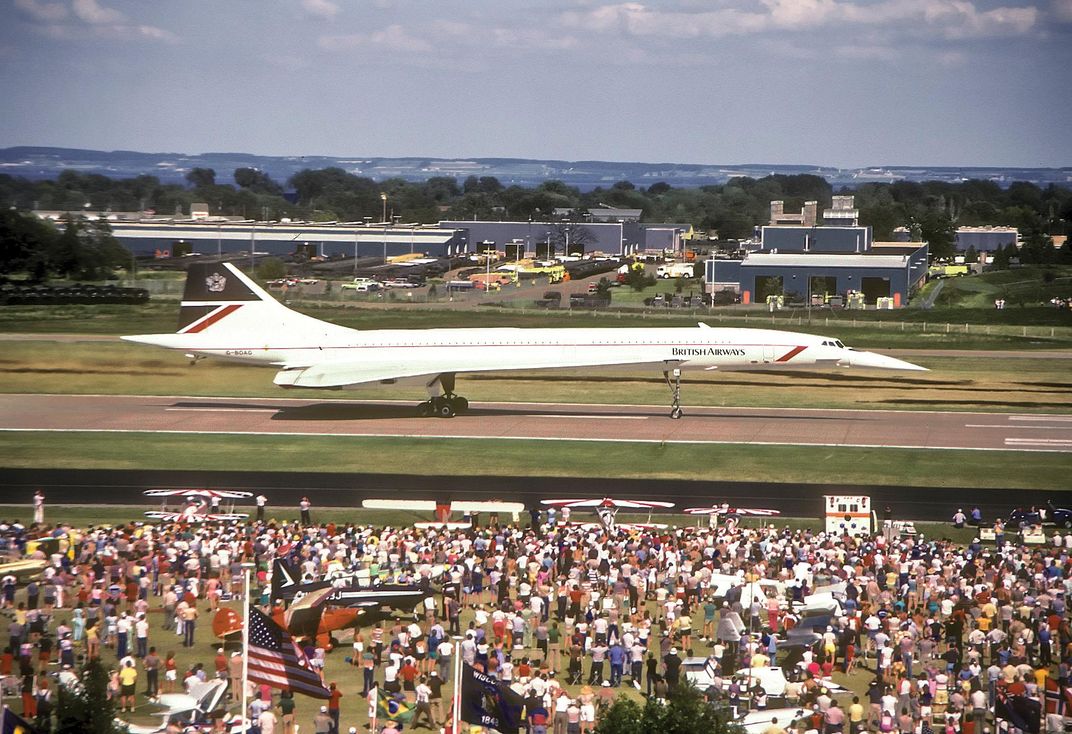

My favorite’s the Mustang, but the odd ones are definitely what stick out, and that’s the cool thing about AirVenture is that it attracts all these one-off, crazy airplanes like the Fairey Gannet. It’s a carrier aircraft developed [in World War II] for anti-submarine action. The wings fold up in sort of a Z pattern. There was a raceplane, Miss Ashley II, and it had two sets of contra-rotating propellers. That was just burned in my memory. In 1998, when the Concorde came, [EAA had announced that it was coming] so we knew we were going to get to see it. I just called it the SST. I was five years old. When we would come over for the day, we would park at one of the schools in Oshkosh and take a bus to the field. I was driving with my mom and dad—we were within the city at that point—and I remember looking out of the car window, and there was the Concorde just above the tree tops, and I was like “Holy cow! There it is!”

A large part of why I’m a photographer is AirVenture. I really love taking pictures in Fightertown in the Warbird area. At sunset, you’ve got all these cool airplanes. I feel at peace there.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e3/52/e3529ee7-4bec-4f02-adde-0885bf7b66c6/2.jpg)

The School of Airplanes

In 2012, Dale Phillips won an award for best Cherokee for his 1968 Piper Cherokee 180D. He got some pointers from the judges and from friends, and went back the following year, when his Cherokee took the Bronze Lindy in the Vintage category. This year’s AirVenture would have been his tenth.

My next goal is to get the second airplane I bought—a Beechcraft Bonanza—going through the rigors of the show. I take it very seriously, and I learn so much from the community there about the airplanes and about the process of getting one in the upper echelon worthy of an award. The vast majority of folks, for example, don’t attend to an airplane’s landing gear. They let it get dirty. You’ve got to crawl up under the airplane to get to it, but the people who are winning are the people who are lying on their backs under their airplanes, polishing everything, all the way down to the rubber on the tires.

You find all kinds of hardware vendors at Oshkosh that sell the nuts and screws and hardware that’s necessary to replace parts that are old or worn out. You learn the network and where to go. There is nothing that you can’t find out. If you want to go to learn, you can literally spend your entire time in forums. My airplane has a Lycoming engine; a Lycoming factory representative is there to put on seminars, so I’ve always attended those. Anything you can imagine, you can find a course for. There’s a common bond of wanting to preserve general aviation for the next generation.

It’s really gonna leave a hole this year not being able to go. The guy I bought my airplane from—we’ve become best friends and we’ve already texted and said “we’ve got to get together this summer, Oshkosh or no Oshkosh”—so I’ll probably be going to Rockford, Illinois to visit him. We’ll do some flying.

Family Tradition

Jim Buxton was born in 1972, and his parents took him to Oshkosh in 1973. “I’ve only missed three years since I’ve been alive,” he says. “Nobody in my family missed one until 2005, when my dad’s health started to go south.” Buxton’s family returned to Camp Scholler in 2008 and haven’t missed a year since.

There was a group of us that gradually got bigger. It became another family. I’m always reminded of what [EAA founder] Paul Poberezny said: “The airplanes will bring you there, but the people are what bring you back.”

One of our family’s traditions—and the 20 or 30 people we camp with—is to go on evening walks. You’d have flashlights to come home, and they’d have lights on some of the airplanes parked in what we used to call Aeroshell Square. One year, they had the Concorde and the B-1 bomber parked nose to nose. They have kind of similar profiles but completely different purposes in life. And one of the guys we camp with—who was a B-24 navigator in World War II—said, “You know, you just kind of wonder what they talk about at night.”

I’ll never forget the Martin Mars. It was out over Lake Winnebago, and we could see it from camp, about five miles away. You could see it plain as day—that’s just how big it was. We’re big seaplane fans, so we went over to the seaplane base. It did a low pass over the lagoon just over the treetops. I was there with my wife and kids, and I just started screaming and laughing like a school kid—all of us did. It was just so unbelievable to see it, and you could hear it long before it came into view. It was actually rumbling the ground. I still get goosebumps thinking about it.

Work for the Fun of It

Pat Blake’s husband Phil introduced her to AirVenture. He had received an EAA junior membership for Christmas when he was 14. The next year, he volunteered at his first EAA convention, in Rockford, Illinois. Today a commercial-rated pilot, Phil is chairman of the residential campground Audrey’s Park. Pat Blake, a nurse, looks out for all the volunteers in the vintage division. Their sons Tayler, 26, and Kimball, 23, are also volunteers.

Pat: Within a couple days of my first visit, I knew I wanted to come back. I’d never seen anything like it. Phil has got what seems to be an encyclopedic memory for every airplane that flies. He can look up and tell you the type, the year, the size of the engine. It was very clear to me how strong his passion was for this.

Phil: What celebrities love about Oshkosh is that they’re not the center of attention. I was sitting under a camper awning with a woman who had just retraced Amelia Earhart’s flight around the world, and I look up and I see Richard Bach [author of Jonathan Livingston Seagull] walk by. I said “Nice to have met you, Lady. Bye.” I chased him down to tell him I really enjoyed his book.

As it turned out, this volunteer community that comes together in April is a pretty tight group. And so the boys ended up with about 15 uncles and a few aunts. And we knew that I could turn them loose safely and there would be any number of people who would be watching out for them or that they could approach for help. As soon as they were old enough to be let loose, I started volunteering as well. They’re both interested in aviation, and they found out how gratifying it can be to work for just the simple fun of it.

Neither has missed a convention since they were born. Kimball would be riding with me on the Gator, and he’d say, “Dad, stop. I want to get out” and I’d say “What are you going to do?” and he’d say, “I don’t know” and later on, I’d see him with the head of security driving around. He’d just go find somebody and they’d go put out fires and this and that.

So I grew—not as fast as Phil and I’m not near as integrated as Phil—but I’m a chairman in the vintage division. I make sure that all the volunteers in the vintage division have food and water and Gatorade. We call it Operation Quench. I feed 550 people. You pick up sandwiches and take the food to the volunteers parking the airplanes. They would never have to pay for any food if they are volunteering. We’re going to take care of them.

A Veteran’s Best Day

For more than 50 years, Amy Crozier has lived near Appleton—a half hour from Oshkosh—but until a co-worker gave her tickets in 2013, she had never been to the show. She’s been a volunteer ever since.

My first experience was in 2013, and I brought my dad. He was kind of hesitant about going. My dad was in the Navy, and on every Friday [of show week], they celebrate veterans. We got there at 11 in the morning and we ended up staying until 7 that night. They treated him like royalty. He got to be in the veterans’ parade. He met so many veterans—one who was stationed near Virginia Beach where he was—and they swapped stories, something he had never been able to do. And we got to see the Old Glory honor flight bringing Vietnam veterans in, and Tony Orlando was there singing. It was so exciting for my dad that on the way home, he said, “Amy, this is one of the best days of my life.” He talked about it for months and talked about going next year. But he had a stroke on December 20 and passed away. It was very unexpected. At the funeral, people kept saying “You’re the one who took your dad to AirVenture” because he had told everybody about it. I decided I needed to give back so I went on the website to volunteer, and they hooked me up with the Vintage group in the Hospitality Red Barn.

While I worked at the Red Barn, I’d meet veterans and invite them to join the parade. Every year, I had a different veteran. In 2016, a World War II veteran who had been a crew chief in the South Pacific—Bob Jacoby—helped rebuild a Ryan ST trainer that sat in front of the Red Barn all week. It was a beautiful airplane. Every time I went there, he was standing next to it—even in the hot sun. He was just so proud. It was his first time at Oshkosh. That Friday, it was an experience just like my dad’s. Before we were waiting for the parade, he saw an airplane he used to be a crew chief on. One of the guys had a compartment open—working on something—and handed Bob a wrench. He had the biggest smile on his face. I went to help with other veterans, and when I came back, there was a crowd of people listening to his stories, laughing and applauding. After the parade, when we got back to the Ryan, he pointed to me and told his friends “There’s a place in heaven waiting for this angel here.” That’s what makes me want to go back to volunteer. I don’t have an aviation background, but I’ve met so many wonderful people and gotten rides in airplanes and I’ve learned so much.

:focal(1946x686:1947x687)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/23/c3/23c394c6-0e46-4a2d-9a6f-e444049dd3d6/15c_aug2020_fireworks_dsc4798edit_live.jpg)