Volcanic Shields of the Moon

Come home with your shield, or on it – Spartan women to their husbands, marching off to war.

Come home with your shield, or on it – Spartan women to their husbands, marching off to war.

From the giant Olympus Mons shield on Mars (600 kilometers across and 27 km high) to the large volcanoes of Venus, shield-building was thought to be a common expression of volcanism on all rocky Solar System bodies; the Moon appeared to be a conspicuous exception. In geology, a shield volcano is a volcanic construct with a broad, low profile made up primarily of thin lava flows with little ash deposits. Earth’s shield volcanoes range in size from a few to more than 200 km for the Big Island of Hawaii, the extent of its base on the sea floor beneath the surface of the Pacific Ocean.

Our understanding of lunar volcanism has been informed and shaped both by images and samples. The large-scale shield volcanoes so prominent on Mars, Venus and Earth were believed to be absent on the Moon. Before the Apollo 11 astronauts visited Mare Tranquillitatis in 1969, we understood that the dark maria of the Moon were volcanic lava plains. Orbital images showed us a landscape of domes, small cones, sinuous lava channels (rilles) and collapse pits – surface features created by volcanic activity. Many of these small volcanic features tend to be clustered in provinces concentrated on the western near side.

Rocks from the maria are basalts, the most common type of igneous rock in the Solar System. They are rich in iron and magnesium and poor in silica. On Earth, when such rocks are molten, the resulting magma has a very low viscosity (i.e., they are very fluid, spreading onto flat surfaces in thin sheets). We understand lunar lavas to be similarly fluid, having erupted in thin sheet-like flows onto the airless surface of the Moon. The maria formed as this geologic process of massive high-volume eruptions built up stacks from the thin, fluid flows which extend for hundreds of kilometers. Scattered within the ancient maria are numerous small volcanic constructs, previously believed to be the only manifestation of central-vent volcanism on the Moon.

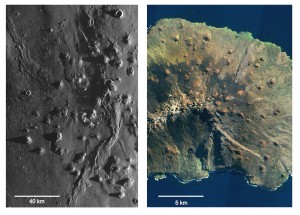

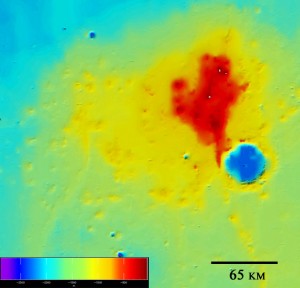

When the Moon’s topography was mapped with laser altimetry (first by Clementine in 1994, then at greater resolution by the Japanese Kaguya spacecraft and NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter mission), it showed clusters of many small volcanoes occurring on topographic highs that are quasi-circular, with low relief and shield-shaped. Pat McGovern, Walter Kiefer (colleagues at the Lunar and Planetary Institute) and I were intrigued by this correspondence. We studied these areas by mapping volcanic features, integrating the new topographic data, and examining their gravity signatures (the amount the local gravitational attraction is enhanced or depleted from normal).

We found that these large shield-shaped topographic swells are made of basaltic lava and display concentrations of volcanic features. Such a structure found on Venus or Mars would be classified as a shield volcano; therefore, we interpret these features on the Moon as shield volcanoes. We have found seven of these large structures on the Moon, ranging in size from 66 to almost 400 kilometers in diameter and from 600 to over 3200 meters in height. Such sizes and shapes are very similar to large shields on Earth, Venus and Mars. The average slopes on these volcanoes are very low, typically less than a few degrees, as would be expected for structures made from very fluid lava. These lunar shields display abundant volcanic features, including domes and cones, sinuous rilles (lava channels and tubes) and collapse features – all common morphologies in terrestrial shield volcanoes.

Although we believe these features are shield volcanoes, this new interpretation is not without some difficulties. Unlike most shield volcanoes on the other planets, none of the lunar shields has a central collapse pit (caldera). However, many shields – especially those on Venus – likewise do not show central calderas. Additionally, while evidence for some lunar shields such as the Marius Hills is pretty convincing (e.g., shield shape, high gravity signature indicating dense stacks of lava), the evidence for others is not as clear. The largest feature we identified, the Cauchy shield, possesses the correct topographic shape and has numerous small cones, rilles, and vents on it, but remote sensing data suggest that the lava thickness in eastern Mare Tranquillitatis is relatively thin, which might mean that Cauchy is not a thick stack of lava as Marius appears to be. We still think that Cauchy is a shield volcano, but acknowledge that our interpretation is tentative and we will continue studying these enigmatic features to better understand their history.

But the real story here is not whether these features are true shield volcanoes or not, but rather, how the advent of new, high-precision data (high resolution topography) can cause scientists to reexamine areas and processes long thought understood and perhaps come to surprisingly different interpretations. We are currently in the midst of a revolution in lunar science. The 42nd Lunar and Planetary Science Conference held this month in Houston highlighted new scientific findings about the history and processes of the Moon. New, high-quality data coming from an international flotilla of lunar orbital mappers – Chandrayaan, Kaguya, Chang’E and LRO – has scientists seriously reconsidering our current understanding of the processes, history, resources and potential of the Moon.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/blog_headshot_spudis-300x300.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/blog_headshot_spudis-300x300.jpg)