The War’s Oddest Dogfight

Over the Atlantic in 1943, it was a battle of the bombers.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/29/a7/29a7df74-9354-49bf-b2a7-20fd975bb195/02a_am2015_milcoll_xviii_maxwell_7_live-cr.jpg)

One of the strangest dogfights—involving three four-engine bombers—occurred in World War II. It happened the morning of August 17, 1943, when an American B-24D Liberator encountered a pair of German Focke-Wulf Fw 200 Condors over the Atlantic Ocean, about 300 miles west of Lisbon, Portugal. The Condors were flying from Bordeaux in occupied France to attack a British convoy sailing from Gibraltar to Scotland. The Liberator, attached to the U.S. Army Air Forces’ 480th Antisubmarine Group, was on the way from its base in French Morocco to protect those British ships.

The 480th had been flying from Port Lyautey in Morocco against German U-boats for several months. Big, boxy, and all-business, the Liberator had the long range required for anti-submarine missions. Modified from its original heavy bombing role, it became an Allied favorite for sub-hunting. These missions were vital to the Allied cause of blunting U-boat attacks on convoys shuttling between Britain and Gibraltar.

The 480th fought the submarine war along with the Royal Air Force’s Coastal Command and U.S. Navy patrol squadrons. When these air arms and the Royal Navy started sinking more U-boats in the Bay of Biscay, between Spain and France, Berlin transferred some of the anti-convoy work from U-boats to the Luftwaffe, increasing the chances that Allied airplanes would encounter German ones.

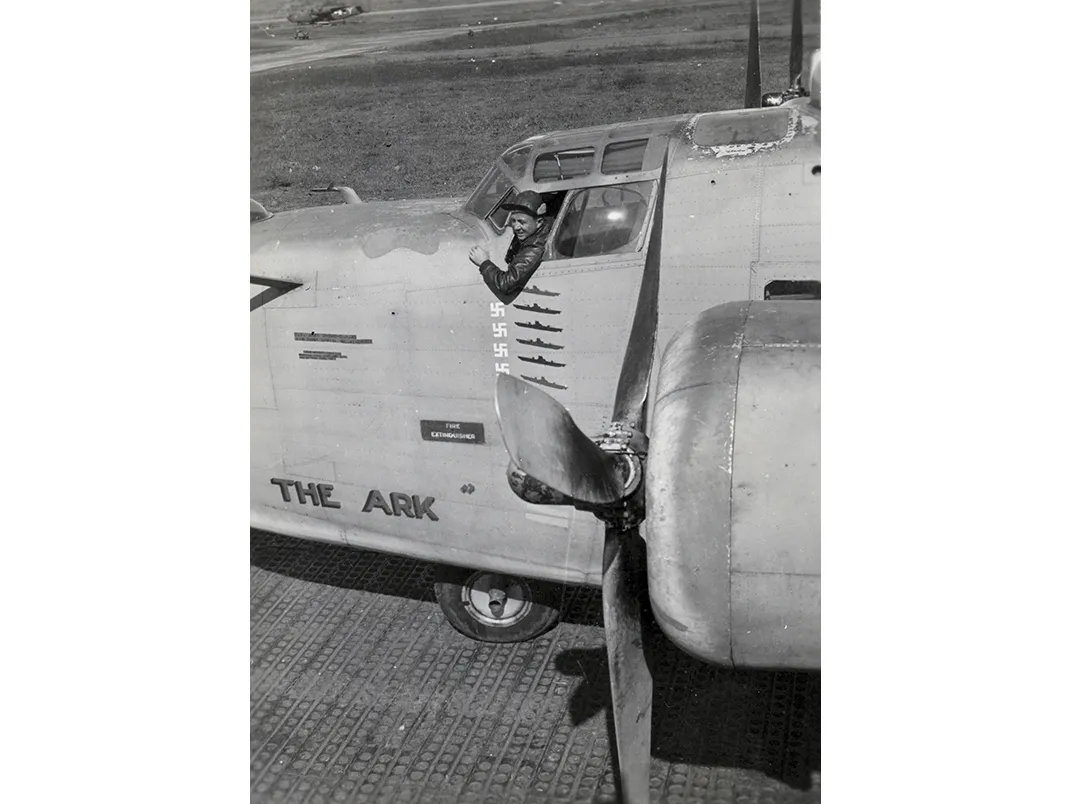

The Liberators had their share of run-ins with German airplanes. From March through October 1943, they shot down nine German aircraft, including five Condors, three Dornier flying boats, and one Junkers Ju 88 multi-role combat airplane; the 480th’s two squadrons lost three Liberators. The Liberator pilot, Hugh Maxwell Jr., now 98 and living in Altamonte Springs, Florida, had been with the 480th since early March, and had fought another Condor about a month before the August dogfight. Flying parallel courses, the two bombers fired at each other, and Maxwell’s gunners scored hits. The Condor was last seen diving into the clouds with one engine out.

On August 17, the Liberator’s base at Port Lyautey had broken radio silence to warn of the Condors’ approach. Maxwell’s radar operator reported a pair of contacts 15 miles away, and his navigator calculated they would arrive over the convoy at about the same time as the Liberator. That left Maxwell no choice but to engage.

The battle was spectacular. He had never flown fighters—his experience had been in B-18 and B-25 bombers—and he had never been in a dogfight, so the combat that day was the ultimate on-the-job training. He initiated the fight by diving his 28-ton bomber out of the clouds at 1,000 feet on the tail of the lead Condor. He told his gunners to hold fire until they got within range. But the Condor “fired a sighting burst and started hitting me,” he says. “I shoved the throttles and prop pitch forward and closed as fast as I could, and I opened fire. They never came out of their diving turn, and went in on fire. But boy, they had done us damage.”

The second Condor, meanwhile, was firing at Maxwell from behind, and Maxwell’s gunners were returning fire. But the Liberator had lost its number-three and -four engines, and the right wing was full of holes and in flames. The bomber was especially vulnerable to attack because modifications for anti-submarine work (enabling the aircraft to carry more fuel and a maximum load of depth charges) had required removing all the armor plating that protected the crew. So when the Condor’s bullets struck, “all of us got hit by shrapnel and our hydraulic system was knocked out, our intercom radio system was knocked out, the whole instrument panel was knocked out,” Maxwell recalls. Fortunately, one of the crewmen was able to jettison the depth charges.

“As I realized that our right wing would no longer fly and I couldn’t raise it, and was trying to hold left rudder and aileron, my left foot kept slipping off the rudder pedal,” says Maxwell. “I looked down and said, ‘Oh my God.’ My whole left leg and foot were covered with blood, and there was a pool of blood and it was all over that rudder pedal. And I knew I’d been hit in the left side with shrapnel. But then I realized: It ain’t blood, it’s hydraulic fluid.

“At no time did I feel heroic or any of that kind of stuff,” he says. “Hell, I was scared. I didn’t want to die, but I had to do whatever I needed to do. The thing that sticks out in my mind the most was when I realized we were going to be crashing into the Atlantic Ocean, and I thought we were goners. But in a last-minute desperate effort to avoid catastrophe, I kicked in full right rudder and threw the plane into a skid, and sure enough, instead of our cartwheeling and breaking up and exploding, the water put the fire out, and the airplane broke in three pieces, but it didn’t explode or burn.” Seven of the 10 crew members survived.

The second Condor was seen mushing over the waves at low altitude with its number-three engine out. The pilot was able to stay in the air; he made it back to Bordeaux, but his airplane crashed and burned on landing, according to one source. All crew members reportedly survived.

Maxwell’s crew was quickly picked up by one of the convoy’s escorts, the British destroyer Highlander. It also picked up “four survivors from that lead Focke-Wulf 200, two of whom died that night because they were so badly burned,” Maxwell says. The events of the day amounted to “probably my worst experience.”

In a 1989 interview with the Imperial War Museum in London, the Highlander’s captain, Colin William McMullen, described the dogfight as “really like a sort of Jules Verne scene, with these two enormous aircraft weaving about, shooting at one another.” After rescuing the Liberator crew, “who were extremely angry at being shot down,” McMullen said the ship “dashed off and found where the Focke-Wulf had gone into the sea. And there were three Germans swimming for Portugal, which was rather a long way away, and we picked up the Focke-Wulf crew. And as they came on the upper deck up the ladder, [they] came face to face with the American crew. And it was only by great tact that we managed to prevent them continuing the engagement on our upper deck.”

But, Maxwell says in an email, “There was no confrontation, other than what was done by tail gunner Milton Brown. I would never have condoned it, but Brownie snatched the epaulet off the shoulder of the [German] pilot’s uniform and later gave it to me.”

For his actions that day, Maxwell was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross, and the 480th ultimately won a Presidential Unit Citation. Maxwell went on to become a B-29 instructor pilot and finished his career in Air Force intelligence, retiring in 1969.