A New Book Profiles the Watchmen Who Guard America Against Nuclear Attack

Twenty-four hours a day—every day—U.S. Army soldiers are ready to defend the United States against incoming missiles.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ea/90/ea904194-29d2-4246-bc01-ac7e8037f9ef/fort_greeley.jpg)

Dan Wasserbly, the editor of Jane’s International Defence Review, is the author of The 300: The Inside Story of the Missile Defenders Guarding America Against Nuclear Atttack. He interviewed many of the 300 men and women who make up the 100th Missile Defense Brigade, based at Schriever Air Force Base in Colorado Springs and at Fort Greely in Alaska. Working in teams of five, these soldiers pull 12-hour shifts, ready to launch silo-based interceptors to destroy nuclear warheads in space. Wasserbly spoke with Air & Space senior associate editor Diane Tedeschi in June.

Air & Space: Why did you decide to write this book?

Wasserbly: I had been writing about nuclear weapons and missile defenses as an editor at Janes for years, and I originally planned to write an academic history of the technology and how it was developed. But in my early research I began meeting the soldiers who operate the technology. They have this incredibly difficult and important job, yet were essentially unknown even within the U.S. Army. The Pentagon created this 300-soldier brigade from scratch and asked them to defend against warheads in space, and their stories were extraordinary. So the project morphed more into the soldiers’ history.

Does the job of standing missile watch have to be done by humans?

There is a significant amount of automation involved, and the mission would be impossible without it. But the soldiers are there to act on orders from the head of Northern Command, who gets orders from the secretary of defense. The software would launch interceptor after interceptor until there were no more, but human crews are there to tell the system what to defend, when to hold fire, and where to take risks. They’re also there in case of some fiasco, and they train nonstop to fight in any scenario: communications failure, fire in their control node, Northern Command goes offline, one missile incoming from North Korea, 10 missiles incoming from North Korea, and on and on.

How do the crews working the midnight shift stay alert?

As you’d expect, it’s not a popular shift. Each crew has enough of those shifts in a row that their bodies adjust to being nocturnal, but I think it gets difficult for soldiers with families. Their spouses and children stay on normal daylight time, and trying to squeeze in overnight shifts and then attending to family during the day can be exhausting. Though they typically don’t enjoy living like a vampire, every crew member I spoke with said sitting down at their console with their crew and conducting such a weighty mission was invigorating enough. Also coffee and energy drinks.

Do the missile-watch crews tend to skew young in age?

Each five-soldier crew has a range of ages and ranks. The lowest is a sergeant and highest is a lieutenant colonel, which creates a unique dynamic. A sergeant is a long way down from a lieutenant colonel, and soldiers of those ranks would not normally sit and chat or work together for hour and hours. But the mission requires quick and honest input from every operator, so rank matters but so does experience. It’s a very different structure from the rest of the Army, closer to the Special Forces community.

And there certainly is burnout. They try to proactively manage that. Crew members typically work 18 to 24 months before being offered another assignment in the brigade, which allows them to rest with a nine-to-five type job. There are fewer assignments available to the more senior-ranked soldiers so it can be trickier for them, but those are often the ones who have been doing this job for years and love it and don’t mind staying out there.

What type of people are drawn to work as missileers?

Every crew member I met showed obvious pride in what they do, and once in the brigade many of them fight tooth and nail to stay in. Much of that is because of the seriousness of their job, which is defending the United States against nuclear missiles.

To an outsider, the crews sit in a windowless room at computer consoles for hours upon hours and wait for an attack that we all hope will never come. It seems boring, and really sometimes their job is boring. But many of the crew members are veterans of Bosnia, Iraq, and Afghanistan, and those deployments could be boring too. Except this brigade isn’t defending American interests abroad: It’s defending Americans at home. That gives the crews an enormous sense of responsibility, and it’s something they’re specifically seeking. They’ve all volunteered and worked for this even though it’s such a difficult job. So said another way, they’re overachievers and proud of it.

What is the most surprising thing you learned while researching this book?

Pretty much everything I learned about Fort Greely, in the center of Alaska, was surprising. That’s where most of the interceptors wait in silos and where most of the soldiers in the unit live and work. There’s the cliché of “sending so-and-so off to operate a radar tower in Alaska”—like that would be a social and professional punishment. But there’s also the romantic Jack London version of Alaska, and that’s what most of the soldiers are seeking there. It’s not an easy life, mostly because the sun disappears for much of winter, and it can be dangerous. One of the soldiers was attacked by a bear, another by a moose. Some hate it and leave as soon as they can, but most of them stay. They build houses near the fort and raise families in the tight-knit community and even retire there. I couldn’t do it because of the darkness, but it’s beautiful when the sun is out.

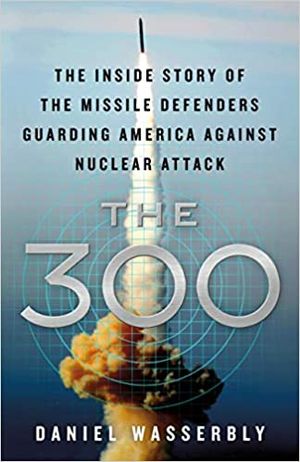

The 300: The Inside Story of the Missile Defenders Guarding America Against Nuclear Attack