Airports You’d Actually Like to Visit

Some are no longer just the beginning or end of a journey. They’re destinations unto themselves.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ee/35/ee35bbe3-fadc-4dbf-9c76-549bad636287/29h_on2019_sommerfest2018_7245_live.jpg)

Who would go to the airport these days if they didn’t have to? Sherri Moss, for one. She took her three-year-old niece and five-year-old nephew to nearby Pittsburgh International Airport one recent afternoon—a 90-mile round-trip from their home in Irwin, Pennsylvania—not to fly but to gawk at the airplanes and grab lunch.

“They love planes, and they are just excited to be here,” she says. “I’m excited to be back in the airside terminal without a plane ticket.”

That’s music to the ears of airport CEO Christina Cassotis, who two years ago unveiled the “myPITpass” program, the first initiative since September 11, 2001 to permit non-passengers into secure areas at a U.S. airport. Others visiting Pittsburgh International just to soak up the scenery include the Vasiladiotis family of Bavington, about 10 miles southwest of the airport.

“We come out frequently for the myPITpass program because we love being at the airport,” says Luke, the paterfamilias of the nine-strong Vasiladiotis clan.

The 2001 terrorist attacks ushered in a dour era for airports around the world. Sweeping measures were taken to discourage non-passengers from hanging around terminals. Romantic farewells at the departure gate were relocated to the tail end of snaking security lines under the hardened gaze of Transportation Security Administration guards. Eager relatives waited for arriving loved ones by dingy baggage carousels or camped in cellphone lots. A generation of kids grew up without an afternoon excursion to see big jets fire their engines and taxi toward the runway. Passengers who did cross the cordon found themselves in featureless spaces where the cost of sitting down was an overpriced bite at a generic chain eatery or bar.

But the memory of the pre-9/11 good old days lived on in Pittsburgh, Cassotis discovered, when she moved there from her native Boston in 2015. “Wherever I would go to talk to anybody in the community, one of the top five questions I got was, ‘When can we go back airside?’ ” By “airside,” she means beyond the security cordon, to the gates where passengers board.

Cassotis’ predecessors had already managed to institute one “open day” each year around Christmas, replete with Santa Claus and a massive tree, which drew crowds of up to 1,500. Pittsburgh International was one of a few airports around the United States linked to an on-site Hyatt Hotel whose guests could clear security and wander the premises. Others include the airports at Detroit and Dallas/Fort Worth.

Cassotis decided it was time to make an airport visit an everyday occasion again. Thirty-three bureaucratically arduous months later, in September 2017, the TSA and its parent structure, the Department of Homeland Security, agreed. “There was no real pushback,” Cassotis says, perhaps just a bit disingenuously, to summarize her odyssey through Washington, D.C. in search of a green light. “Sometimes to do something outside the box, it takes a lot of people and departments to sign off on it. It wasn’t like there was one guy or woman we could go talk to.”

Her persistence paid off in a common-sense program that parts the security curtain without shredding it. Non-passengers can cross to airside from 9-to-5 on weekdays, the slower hours for flights. They check in at a separate myPITpass counter where ID is presented and scanned against no-fly lists, an almost instantaneous process these days. Then they pass through TSA security like anyone else, with the proviso they have to step out of line if it gets too long.

That hasn’t happened yet. The going-on-two-year experiment has added less than a blip to Pittsburgh International’s traffic, averaging about 100 visitors a day against 25,000-plus passengers. But that’s enough to facilitate a lot of memorable occasions: parents at the gate to meet their arriving daughter burdened with bags; families seeing off soldiers on deployments; #avgeeks out in force to admire the British Airways Boeing 787s that recently began nonstop service to London.

Allowing non-passengers through security looks like it might be catching on, slowly and cautiously, with other airports more or less in Pittsburgh’s category; that is, those attached to mid-size metropolitan areas that don’t face the pressure of hubs and are accessible without hellacious traffic. Pittsburgh International is about 16 miles west of downtown, a cruise of 20 minutes for less than $30 via Uber at an off-peak hour.

Tampa International Airport lately kicked off an All Access program that falls a bit short of the name. Access is limited to Saturdays and capped at 25 visitors to each of the four airsides that surround the main terminal, and visitors must register 24 hours in advance. Sea-Tac Airport, serving Seattle and Tacoma, Washington, ran a pilot Visitors Pass program late last year, which opened the gates Tuesday-Saturday with a cap of 75 non-passengers daily. It drew 1,100 visitors over six weeks.

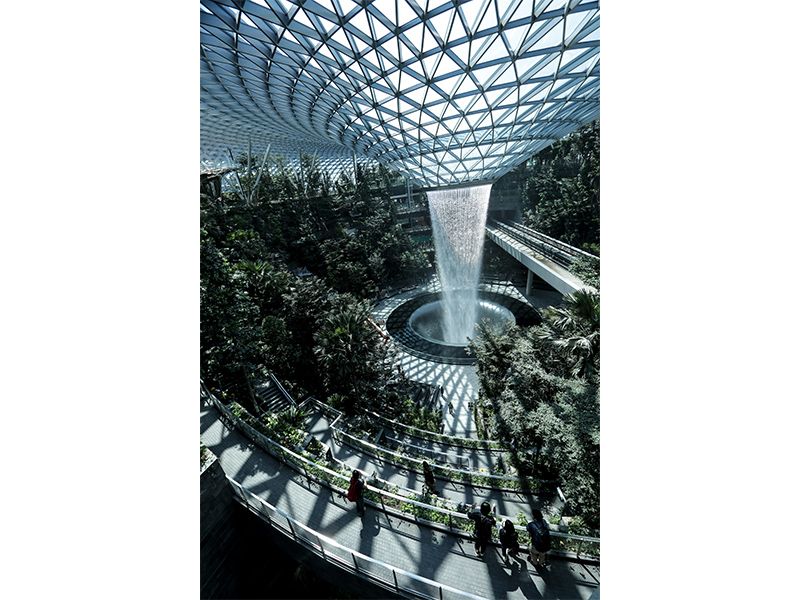

In the broader sense, though, Pittsburgh and the others are part of a global vanguard pushing back against the gigantic genericism of the post-9/11 era. Initiatives small and large aim to reintegrate airports into their surrounding communities. The most ambitious programs along these lines are in foreign cities that are more compact and have better mass transit than U.S. metros. Singapore’s Changi, already widely considered the world’s best airport, just opened the Jewel shopping mall on ground formerly occupied by parking. The $1 billion-plus construction, which is linked to the air terminals but separated from “sterile” areas, boasts the world’s tallest indoor waterfall (130 feet!), flanked by nearly 300 shops and restaurants. “Singapore discovered they have more shopping at Jewel than on one of the main shopping streets,” says Julian Fentress, marketing director at Fentress Architects, the family firm that is among the leading designers of airports. “People come there from all over Singapore Island.”

A more modest example is the Munich Airport Center, a mall attached to the Bavarian capital’s 1990s-vintage terminal complex. It advertises the “largest covered open-air space in Europe”—a little more than six square miles—including, naturally, a big beer garden.

U.S. airports have been more focused on accommodating passenger volumes that have surged by one-third over the past decade to reach one billion annually in 2018. But some thought has been spared for localization and ambiance.

Destination cities like San Francisco, New Orleans, and Austin have led this movement, says Henry Harteveldt, founder of Atmosphere Research Group, a market research firm that serves the global travel industry. A new terminal under construction at New Orleans Louis Armstrong International will showcase the city’s musical heritage with a jazz garden accessible to the general public. An arching glass structure lets the southern sunlight pour in and “evokes the geography of the Delta region and soft curves of the Mississippi River,” said chief architect Cesar Pelli. (Pelli passed away at age 92 on July 19.) “Airports today are basically dreary places that are functional but sterile,” Harteveldt comments. “But some are doing a better job of incorporating their communities.”

Not every American city has Mardi Gras or SXSW to pull in visitors, though, and not every American airport is bursting at the seams. Some remain overbuilt from the last extended economic boom in the 1990s.

Pittsburgh is a prime example. The current terminal, 75 gates extending in an X shape around a central core, opened in 1992 at a cost in the $1 billion range. US Airways, a rising industry star at the time, had grown out of western Pennsylvania’s own Allegheny Airlines, so routing flights through Pittsburgh was only natural. The luxurious facility was meant to double as a regional shopping mall and schmoozing nexus. “The geography around here is so hilly, there aren’t that many places you can easily get to,” Cassotis notes. “This was built as a global megahub, and people were interested.”

The 9/11 attacks brought an abrupt end to the schmoozing and shopping, while airline economics eroded the core business. US Airways shifted its hubs to Charlotte and Philadelphia in 2004 after a pricing dispute with the Pittsburgh authorities, and was eventually folded into American Airlines. Pittsburgh International still languished when Cassotis arrived a decade later—most days, only about 40 of the airport’s 75 gates are in use—despite a spirited economic and cultural revival in the city. “When I first got the call from Pittsburgh, I said ‘I’m not interested,’ ” Cassotis recalls. “I hadn’t seen anything happening here for so long.”

Daughter of a Pan American Airways pilot, Cassotis was no stranger to aviation industry vicissitudes, having watched the extended death throes of the fabled carrier up close through the 1980s. (Dad himself did fine, transferring to United Airlines’ expanding Asian service.) It didn’t stop her from getting the bug though. After majoring in English at U. Mass Boston, she landed a job in public relations at Logan. Then she spent 16 years at the consulting firm ICF—SH&E, rising to the position of managing officer of airport services, supervising a team of advisors to airport operators, investors, and governments around the globe. Living in southern Maine and raising a family, she was far from craving a change of scene.

Pittsburgh’s enthusiasm changed her mind, she says. Aside from the de rigueur meetings with the board, she and other candidates got an earful from business leaders who saw the airport as a key missing piece in the erstwhile Steel City’s renaissance as a tech and brain center. “This is a community that understood what it lost,” she recalls.

Pittsburgh’s captains of industry and philanthropy stayed engaged after Cassotis came on board. “I made a statement early on that passengers should know they’re in Pittsburgh,” she recalls. “The head of the Richard King Mellon Foundation called and said, ‘We want to sponsor that.’ ”

Thus was born the airport’s Creating a Sense of Place program, the foundation combining its financial muscle with Pittsburgh’s formidable cultural and intellectual assets to achieve that end. Banker Andrew Mellon and steel magnate Andrew Carnegie were both wildly wealthy Pittsburgh residents who acquired great influence in the late 19th century, and whose philanthropy helped to establish a number of the city’s cultural and educational institutions. Innovative minds at Carnegie Mellon University outfitted the airport with a nifty “EarthTime” installation, where a viewer’s touch can reveal time-lapse illustrations of, say, deforestation or refugee flows since the 1980s. Crossing to airside, passengers are confronted by a 30-foot-long Tyrannosaurus Rex skeleton, jaws agape, donated by the Carnegie Museum of Natural History. The ticketing concourse one flight up is graced by a monumental hanging mobile that Alexander Calder created for a Carnegie Institute exhibition in the late 1950s, and titled simply Pittsburgh. The Frick Museum unfurled a rotating exhibition space in Concourse B. The Children’s Museum of Pittsburgh created the Kidsport lounge to keep little ones from going crazy in case of flight delays.

One local Pittsburgh hero born later than Carnegie and Mellon has his own place at the airport. A tableau marked Welcome to the Neighborhood honors Mister Fred Rogers, who broadcast his iconic children’s show for 33 years from the local PBS affiliate. Beloved Pittsburgh eateries like Primanti Brothers—home to the Almost Famous sandwich that puts the fries and cole slaw inside the bread—and Penn Brewery, which “adheres to the strict quality standards of the 16th-century Bavarian Reinheitsgebot purity laws,” have opened airport branches. About one-third of Pittsburgh International’s 77 concessions are locally owned or operated, the airport says.

Pittsburgh business has also boosted the airport just by continuing to flourish. The city now houses Google’s fifth-largest campus, for instance, which has helped underpin two nonstop flights a week to San Francisco. Overall passenger volume has climbed from just under eight million in 2014, just before Cassotis’ arrival, to 9.7 million last year, while the number of nonstop destinations has expanded from 37 to more than 60 during that period.

Whether Pittsburgh’s sense-of-place, back-to-the-community ethos can catch on at an airport near you depends on which airport is near you. For big hubs, there is no way back to the innocent days of hanging around to see Dad or Grandma off. “Large airports like O’Hare or LAX have been reconfigured in ways that I can’t imagine greeters being allowed in,” says Glenn Winn, a former chairman of the International Association of Aviation Security Officers, who now teaches at the University of Southern California.

Another headwind facing the community airport trend is stretched TSA resources. The $5.60-per-traveler fee instituted after 9/11 to fund airport security now covers only 40 percent of the cost, according to administrator David Pekoske. Congress has to fill in the rest. Pekoske proposed hiking the levy to $8.25 by 2021; legislators are studying the request.

There is also one economic mega-trend pushing toward imaginative strategies for reintegrating airports with their surrounding communities: parking, or rather its expected decline. Parking lots not only take up a lot of space at the airport, they produce a lot of profit, far out-earning concession fees from shops and restaurants, Cassotis says.

Ride-sharing services like Uber and Lyft threaten that. National statistics are hard to come by. But LAX, as good a bellwether as any, reported flat parking revenues last year (at a cool $96.7 million) while passenger volume rose more than three percent.

The years since 9/11 have seen a quiet sense-of-place revolution in the United States. Anonymous subdivisions are out, historic downtowns back in. Farm-to-table restaurants and microbreweries are grabbing market share. Cutting-edge companies have junked remote office parks for walkable campuses. Security concerns have kept airports out of this stream. But at long last, they are beginning to experiment with airport rehumanization.