Korea, the First Jet War

It was a long, hard fight for both the communist and United Nations jet pilots who battled for the right to rule MiG alley.

:focal(666x416:667x417)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/08/5c/085c8d11-eb9c-44a0-8dad-ecf8c4a1ad5c/f-86.jpg)

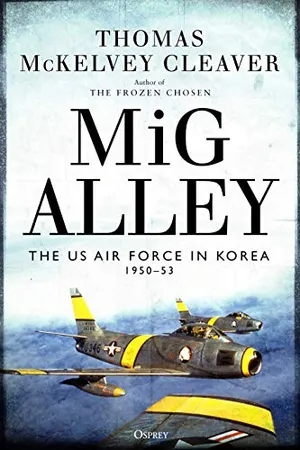

Aviation historian Thomas McKelvey Cleaver is the author of MiG Alley, a new book about the Korean War. While U.S. Air Force pilots did establish air superiority over North Korea, this achievement was not a cakewalk. The aerial skirmishes between MiG-15s and F-86s were far more evenly matched than was initially reported. Drawing from American, Russian, and Chinese sources, Cleaver presents a more accurate account of the Air Force’s accomplishments in Korea. Senior associate editor Diane Tedeschi spoke with Cleaver in February.

Air & Space: Why did you decide to write this book?

Cleaver: The official Air Force history of the air war in Korea does not comport with reality. All of the ‘facts’ turn out to be unexamined 70-year-old wartime propaganda that has fossilized into fact. Pretty much anything you think you know about the Korean War is untrue.

Why has the Korean War become known as the “Forgotten War”?

It’s become forgotten because it’s the first war America didn’t win. There’s that famous line in the opening of the movie Patton that Americans love winning and won’t tolerate losing. And that’s the line that has defined the Korean War for the past 70 years.

What is your opinion of the MiG-15?

The MiG-15 was a rugged airplane that could take a lot of punishment. The MiG was not as advanced aerodynamically as the Sabre, which is why it couldn’t go supersonic. The horizontal stabilizer was in the wrong place (up on the vertical fin).

Did the U.S. Air Force learn anything in Korea that prepared it for Vietnam?

Neither the U.S. Air Force nor any other part of the American government learned a thing from Korea that prepared them for Vietnam. Dean Rusk, who was undersecretary of state for far eastern affairs in 1950, and was one of the cheerleaders for crossing the 38th Parallel and “rolling back communism,” not only paid no price at the time for his wrong position, he was the secretary of state 10 years later—telling President Kennedy to get involved militarily in Vietnam. Everyone in the Army and Navy at the time agreed with Admiral Clark, the commander of the Seventh Fleet in Korea, that the interdiction campaign didn’t interdict. And so the Air Force tried the exact same thing the exact same way as they had in Korea, in Vietnam, and got the same result.

How would you describe the transition to jet-powered combat by U.S. forces?

It was difficult, since most of the Air Force jet airplanes had not been designed for use in a war like Korea. They had to build extensive modern airports in the country for the jets to operate from. At the outset of the war, Air Force jets could operate only from bases in Japan, so they had only 15 minutes of combat time over the battlefield before they had to turn around and go home. If the Navy hadn’t survived the Air Force attempt to get rid of naval aviation after World War II and hadn’t had the carrier Valley Forge there, and the Marines hadn’t had two squadrons of old World War II Corsairs on two little escort carriers—all of which could provide unlimited battlefield air support—the United Nations forces would have been driven off the Korean peninsula in the first 90 days.

When Valley Forge and the British carrier Triumph attacked Pyongyang on July 4, 1950, they surprised the other side, who didn’t think any UN aircraft could fly such a mission. The attack led Stalin to decide not to provide direct Soviet air support to the North Korean army, which meant they wouldn’t win. The Air Force has never argued against aircraft carriers since then.

Tell me about the most memorable person you interviewed for the book.

Well, unfortunately, nearly all the people who were involved are long gone. I was very fortunate, though, to be given access to the archive of Sabre Jet Stories, the magazine of the now-defunct Sabre Jet Pilots Association, which had a lot of first-person stories written by the guys who were there—stories that were at great variance with the official history. I was able to interview one combat veteran, James Thompson, who was a wingman in the 51st Fighter Wing. He explained how life was in the unit. He was very memorable for the fact that he came home from the war, became a Presbyterian minister in Alabama, and was one of the very few white southern ministers who participated in the Civil Rights Movement. He first worked with Martin Luther King in the Montgomery Bus Boycott and had dinner with Dr. King the night he was assassinated. I was lucky to get to interview [Thompson], since he passed away four months later.

What is the biggest misconception about the air war in Korea?

The biggest misconception is that the Air Force reigned supreme throughout. This is most obvious in the mythology of the 10:1 victory total. What mattered is that because of the guys in the Sabres, the enemy air force never appeared over the battlefield, because if it had, the United Nations forces would have been defeated. That was the victory the Air Force obtained, and it doesn’t need any propaganda to make that claim.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.