What’s Real, and What’s Not?

At the National Air and Space Museum, some artifacts are more genuine than others.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/19/ac/19ac371c-5be5-406e-b6b2-1a82a3b28ddc/apollo_11_lunar_module.jpg)

Apollo Lunar Module

Visitors to the National Air and Space Museum often wonder aloud about the authenticity of the artifacts they see. At the Lunar Module on display, we’ve heard the question: “Isn’t it still on the moon?”

The module on display, LM-2, was used as an engineering backup prior to the moon landing. It was one of 12 lunar modules built for Project Apollo, and was modified to look like the Apollo 11 Eagle for display at the Museum.

LM-1 and -2 were built to orbit Earth unmanned in order to test separation, rendezvous, and docking with the similarly unmanned command and service modules. But with the success of LM-1’s test flight, LM-2 was diverted to ground testing. Never intended to land, the two modules were built without landing gear; the gear were later added to LM-2 during the module’s drop tests, which simulated the speeds and possible impact angles that astronauts might experience.

Because LM-2 was not man-rated, this display model does not have the flameproof blanketing added to lunar modules after the 1967 Apollo 1 fire. According to curator Robert Craddock, “The only real differences between LM-2 and [the Apollo 11 module] LM-5 are a few panels that were made of different materials, and thus have a different color to them. Also missing from LM-2 are the calibration marks on the commander’s window used for navigation during the descent to the lunar surface, the optical alignment telescope, and the flight computer.”

In 1970, the ascent stage of LM-2 was displayed in the United States pavilion at EXPO 70 in Osaka, Japan, along with a piece of lunar rock, the Spirit of St. Louis, and artifacts from around the country. When it returned to the Smithsonian, the ascent stage was reunited with its descent stage, and the ensemble modified to look like the Apollo 11 lunar module. There is a flag on display with the lunar module. A reporter once asked communications specialist Isabel Lara if the Museum had in its collection the flag that Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin planted on the moon. No. That’s still on the moon.

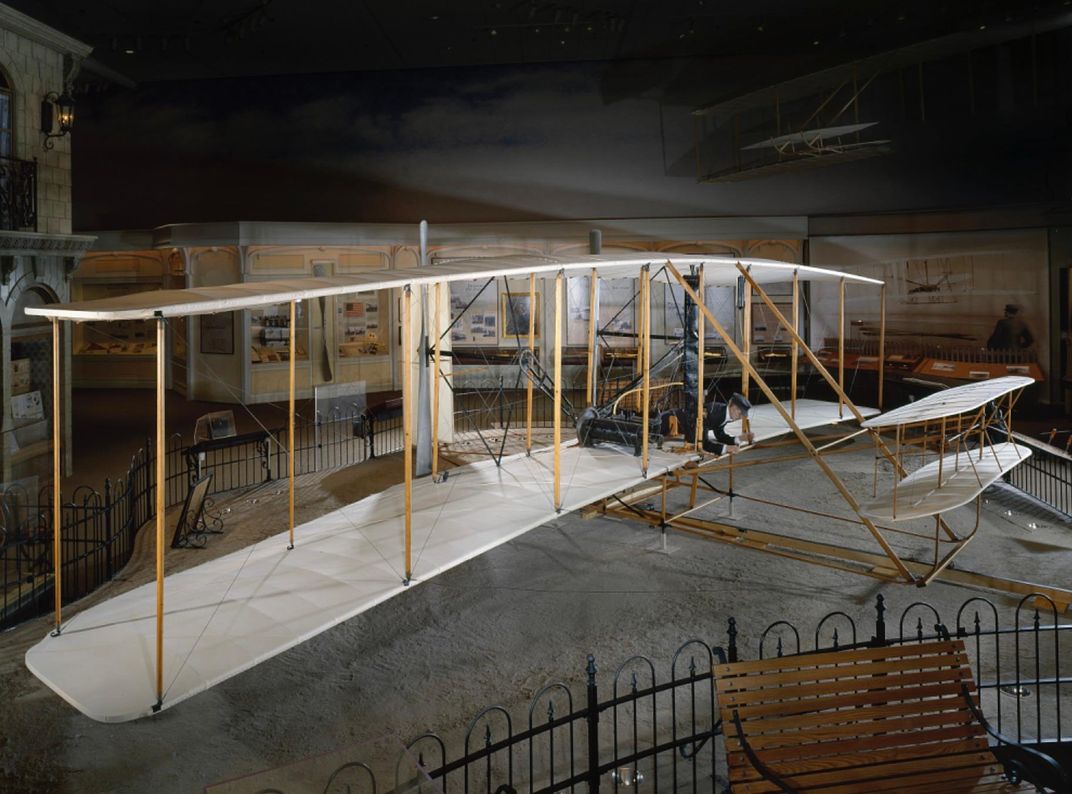

1903 Wright Flyer

Many visitors have found it hard to believe the statement on a placard placed by the Wright Flyer: “This is the actual airplane built and flown by the Wright brothers in 1903.” Here’s a capsule history of that object.

After taking a tumble at Kitty Hawk, the 1903 Flyer was crated and stored in a shed behind the Wright brothers’ bicycle shop in Dayton, Ohio, then ignored for more than a decade. When a flood hit the area in 1913, the crates were submerged in water and mud for 11 days. It wasn’t until 1916 that the world’s most famous aircraft was uncrated and reassembled for an exhibition at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

In 1928, Orville Wright and mechanic Jim Jacobs refurbished the Flyer extensively and replaced its fabric covering before loaning the aircraft to the Science Museum in London. (The original fabric was set aside; portions still exist.)

The Flyer was donated to the Smithsonian in 1948, which immediately put it on display; it has been on view ever since. It received a quick cleaning in 1976 before moving into the then-new National Air and Space Museum building, but in 1985, it was disassembled, cleaned, and preserved. As part of the preservation, a new fabric covering—as similar to the original as possible—was applied. Using the stitching on the original wing as a template, the Museum’s staff stitched the fabric exactly as the brothers had done in 1903.

Space Shuttle Discovery

There is no question that the space shuttle Discovery is the actual orbiter that traveled more than 148,221,675 miles before arriving at the Museum’s Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in April 2012. While NASA’s repair crews would have replaced the battered shuttle tiles immediately upon Discovery’s return, the Museum wanted to show the effects of reentering Earth’s atmosphere, so visitors to the shuttle exhibit see the spacecraft in all its scorched glory, just as it appeared the day it landed.

But before Discovery could go on display, some hazardous materials had to be removed. As Valerie Neal, a curator in the Museum’s space history division, says, some of those materials included propellant residues in the orbital maneuvering system, reaction control systems, and auxiliary power units. Also discarded were the explosive charges found throughout the shuttle, including in the landing gear, side hatch, and drag chute system.

Some items, like the main engines, were removed but remain with NASA, for possible use on other projects. Other items, like the shuttle’s galley, were reinstalled in order to keep Discovery as close to its flown condition as possible.

Every artifact in the National Air and Space Museum is the real thing, though some real things, like the Hubble Test Telescope, are test vehicles instead of flight hardware. If there is any doubt, the labels in the galleries will tell all.