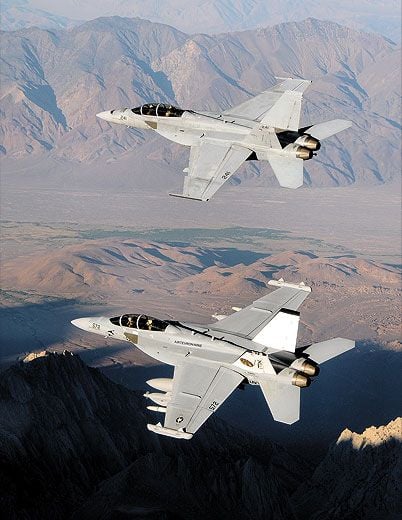

When Hornets Growl

The new, supersonic face of e-warfare

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/FM-2011-when-hornets-growl-1-FLASH.jpg)

Two hours north of Seattle, Washington, at the eastern end of the Strait of Juan de Fuca, the entrance to Puget Sound is guarded by a citadel dedicated to the aerial mastery and manipulation of one of the universe’s fundamental particles—the electron. The site, Naval Air Station Whidbey Island, was originally envisioned as little more than a waypoint for patrol aircraft scanning the Sound for invaders in World War II.

Today, the station has evolved into the headquarters for the Navy’s airborne electronic attack mission, a shadow world where the electromagnetic spectrum—the range of radiation frequencies—is the battlefield, and jets firing radio waves, microwaves, and infrared waves instead of bullets can wreak havoc without a trace. Now, as the Boeing F/A-18F Super Hornet morphs into the EA-18G Growler, the Navy’s e-warfare capability has gone into afterburner.

In electronic warfare, various pods and antennas on an airplane send and receive these high-powered electromagnetic signals to disrupt, suppress, or disable an enemy’s radar-based defenses and communications networks. Called aerial electronic jamming, the practice can make a flight of attack airplanes accompanied by a Growler vanish from enemy radar screens in a storm of disorienting electromagnetic noise, like an orchestra drowning out a bugle. Or a Growler can slouch into passive mode, eavesdropping on the enemy for extended periods to gather intelligence.

For some 40 years, those at Whidbey have been practicing the black art of jamming from inside the cockpit of Grumman’s drumstick-shaped EA-6B Prowler. But that aircraft, which flummoxed a generation of enemy radar operators in Vietnam, is aged, overbooked, maintenance-needy, and downright slow.

In 2009, the first operational squadron of EA-18G Growlers, the Prowlers’ successors, began tearing through the skies around Whidbey. By the end of 2014, the Navy plans to take delivery of 114 Growlers. At $67 million each, the G comes with a lot of bells and whistles.

The electronic attack community likes the Growler’s speed and its ability to fly from either airfield or carrier deck. Pilots like the fact that it will be able to stand back and jam for other airplanes, called standoff jamming; or, because it’s able to keep up with Super Hornets, that it will provide modified escort jamming in almost all phases of an attack mission, targeting in particular an adversary’s airborne and ground-based anti-aircraft missile capabilities. And everyone likes the cut of its jib. The Growler has the DNA of a fighter, so it is more suited to a Hollywood closeup than its bulbous and blistered predecessor.

Yet those who fly the Growler for the “Scorpions” of VAQ-132 at Whidbey, the first operational squadron, know their place in the world: below the radar. “Oh, we’ll never have a Top Gun movie made about us,” says Lieutenant Commander Eric Sinibaldi, a Scorpion electronic warfare officer. “The problem we have as electronic attack guys is there is no kinetic. You don’t see a bomb blow up.” The only way to confirm how e-warfare methods worked in a given scenario would be to ask the enemy what effects he witnessed.

Jack Dailey, a retired Marine Corps general and the director of the National Air and Space Museum, flew McDonnell RF-4s and jammers in Vietnam, including the Grumman EA-6A, the two-seat e-warfare precursor to the four-seat EA-6B. He also flew the Douglas EF-10B Skyknight, an e-warfare version of the F3D. He confirms that the work was quiet but very intense. “The mission was classified so nobody knew what we did,” he says, a fact largely true of the Growler’s mission now. “We had a song we sang: ‘We’re the senior squadron in the East, we fly the most but we do the least.’ And we did fly a lot. Always airborne, always orbiting, always watching.”

From Allied landings on D-Day to NATO’s bombing campaign in Kosovo in 1999 to the Israeli air force’s reported successful targeting of a Syrian nuclear facility in 2007, militaries that have manipulated the electronic spectrum have had a major advantage.

“If [e-warfare aircraft] are not airborne to support the strike, the strike does not go,” says Commander Jeff Craig, the Scorpions’ commanding officer. “Guys are recognizing the threat today is much more diverse.”

That realization trickles down to the people on the ground who get cover from the electronic warfare mission.

“You come back to the chow hall maybe a couple of weeks after working with [the troops] and actually sit and eat dinner with them,” says Lieutenant Kristen Levasseur, another Scorpion electronic warfare officer. “And they ask you, ‘Were you guys the ones out there that night?’ You say yes, and they tell you the crazy stories about what went on, and thank God you were there.”

E-WARFARE first broke out on the high seas during the 1901 International Yacht Races, now called the America’s Cup. Italian inventor Guglielmo Marconi had planned to provide radio-telegraph updates from a boat to the Associated Press on shore. But a competitor, the American Wireless Telephone and Telegraph Company, eager for an exclusive, constructed a more powerful transmitter. As the racing yachts Columbia and Shamrock II tacked around Sandy Hook at the northern tip of the New Jersey coast, the airwaves that should have carried the Morse code dots and dashes of Marconi’s transmitter were instead saturated with noise from American Wireless, rendering his dispatches indecipherable.

It took just three more years for electronic jamming to truly go to battle. During the 1904 Russo-Japanese War, Russian radio-telegraph stations at Port Arthur on the Chinese coast interfered with wireless communication between Japanese ships trying to shell the Russian naval base there. A decade later, radio jamming went to the battlefields of World War I, but both sides opted more often to gather enemy transmissions. In World War II, Germany struck a blow in the expansion of e-warfare: On February 12, 1942, as the German warships Scharnhorst, Gneisenau, and Prinz Eugen bolted from the bombed-out French port of Brest via the English Channel to the relative safety of German waters, all behind a curtain of German electromagnetic interference, English radar screens turned to gibberish. Known as the Channel Dash, it compelled the Brits to start waging e-warfare in earnest.

Among their first tasks was to address Bomber Command’s losses due to the early warnings enabled by German radar. The RAF turned to the unsung Boulton Paul Defiant, a two-seat, four-gun, one-turret fighter that failed to achieve the stardom of the Hawker Hurricane and the Supermarine Spitfire.

“The Defiant was designed to pull alongside and below German bombers and pour rounds into the engines and fuel tanks, protected from return fire by the bomber’s own structure,” says Les Whitehouse, a British aircraft historian with the Boulton Paul Association. “It could out-turn the Hurricane, Spitfire, and Messerschmitt Bf109. What it could not do was outrun the Bf109.” This made the Defiant vulnerable, so the RAF assigned it to training, air-sea rescue, night patrol, and work with airborne radar countermeasures.

Five months after the Channel Dash, eight Defiants were flying formation over the south coast of England, using “Moonshine,” a new radar technology the Brits had created, to try to fool one of Germany’s powerful Freya early warning radars, this one near Cherbourg, France. Moonshine reradiated Freya’s radar waves back with a larger, identical pulse combined with the natural pulse off the Defiants, giving the appearance that a pack of a hundred heavy bombers was approaching. Before the last pulse of Moonshine had been sent, 30 German fighters were in hot pursuit of a phantom bomber group. Less than two weeks later, Defiants again fooled Luftwaffe ground controllers, who vectored 144 fighters toward an imaginary air raid while a dozen B-17s and their fighter escorts attacked the rail yards at Rouen, France.

“England was not the only country to get into airborne electronic countermeasures during the war,” says Daniel Kuehl, director of the Information Operations Concentration Program at the National Defense University in Washington, D.C. “Everyone did. But the Brits and the Americans were the best at it, and they won. From World War II on, electronic warfare becomes essential to operating and winning a war.” The airborne jamming genie was out of the bottle, and the Defiant had shown that you didn’t have to be fast or glamorous to get the job done.

Which was good news for the homely EA-6B Prowler, the U.S. Navy’s primary jammer since 1971. The airplane, a Grumman A-6 Intruder stretched 4.5 feet and equipped with two more electronic warfare officers in shoulder-to-shoulder back seats, ripples with tumor-like bulges and pods housing the airplane’s jamming equipment. The subsonic Prowler, first flown in May 1968, had electronics that were tailored to counter Soviet-built radar stations launching the Mach 3.5 SA-2 radar-guided missiles that, early in the Vietnam conflict, were downing U.S. Air Force pilots in alarming numbers—one American airplane lost for every two SA-2s fired.

John McCarty, a tour guide and gallery lead at the National Electronics Museum in Washington, D.C., worked for Westinghouse in the Vietnam years developing electronic countermeasures. On visits to South Vietnam, he watched as strike groups returned to base missing airplanes downed by SA-2s. “Pilots made it clear that they would rather have a 500-pound bomb to drop than a piece of mysterious equipment hanging on a wing,” says McCarty. “But afterward they started seeing that aircraft flying with our jamming pods were returning and those [without] were not coming back as often, so the conclusion became obvious.” The Navy began calling up every jammer it could get.

“We had done our workups in preparation to go to the Mediterranean,” says Bob Pettyjohn, a retired Navy captain and Prowler pilot aboard the carrier America. “Ten days before we left, the Navy said, ‘Whoa, not so fast! You’re going to Vietnam.’ Well, the other guys on the boat weren’t too happy about the change in plans, with the exception of the two Phantom fighter squadrons aboard ship who looked at us as the biggest MiG bait ever to come down the pike.

“The first flight we flew over there in the Prowler, when we turned on the jammers, every radar in North Vietnam lit up. They had never seen anything like the Prowler.”

Once on station, Prowler crews found themselves flying at all hours. “They would have a carrier flying noon-to-midnight cycles, and another from midnight to noon,” says Pettyjohn. “The idea was you could shut everything down and people could get some sleep. But since we were covering everybody, they would sometimes have to get up in the middle of the night just to launch one of our airplanes. So the America didn’t like us. I can remember one night blasting off the America at three o’clock in the morning to cover the B-52s. We get airborne and I look in the rearview mirror and see all the lights go off. They were happy we were gone so they could go back to sleep.”

Night and day, the Prowler built up a reputation as crucial to a strike group’s ability to penetrate North Vietnamese air defenses. “I can gladly and gratefully attest to the incredible effectiveness of the Prowlers,” says former space shuttle commander Michael Coats, who flew the Ling-Temco-Vought A-7 Corsair II in Vietnam. “They were fantastic, and a combat pilot’s best friend in a high-threat environment.”

By 2016, the 93 Prowlers still flying (170 were built between 1968 and 1991) will be either the property of the Marine Corps, which plans to fly them until at least 2019, or decommissioned, with a few ending up on a pole in front of an airfield.

“IN THE PROWLER, you had four guys working an older weapon system,” explains Eric Sinibaldi. “Now, with only two guys in the Growler with a newer weapon system, it requires both to be really on the same page to fight the jet.”

Some have joked that the pilot in the EA-6B was just a chauffeur. No one can say that of the Growler. Integrating the pilot into the electronic attack mission involved more than 200 Prowler pilots and electronic warfare officers running numerous missions in the Growler simulator at Boeing’s St. Louis facility. This revealed that it takes a lot more automation, as well as advanced cockpit displays that clearly present critical data, to get two people to do the work of four. “I think it’s fair to say they tend to be a different breed of cat,” says Captain John Green of e-warfare crews. Green runs the Navy’s airborne electronic attack program at Naval Air Station Patuxent River in Maryland. “If the average brain is 14 pounds, maybe Prowler and Growler guys are 16.”

The Prowler’s steam gauges and thumb wheels have been replaced in the Growler with digital, flat-panel displays. And compared to the two-seat F/A-18F Super Hornet, a fully loaded G is 1,400 pounds heavier, with 66 more antennas, an additional half-mile of wiring, and 1.5 million more lines of software code. A Link 16 data exchange network lets the Growler send and receive data with other airplanes on the fly, allowing Growler crews to effectively “peer over the shoulders” of other airplanes in the strike group in real time to see what their radars and other data gathering systems see. The crewmen wear helmet-mounted cueing systems that display targets and flight data on the inside of the visor to enhance their head-up awareness (see “Hard Hat Zone,” Then & Now, Aug./Sept. 2008). The Growler’s electronic countermeasures system, called Improved Capabilities (ICAP) III, was originally deployed on the Prowler. To make ICAP III work in the Growler, engineers had to reconfigure its ALQ-218 jammer. The system’s main receiver, called the “football” when it was perched like the Super Bowl trophy atop the Prowler’s vertical tail, has been split into a pair of sleeker antennas, one on each of the Growler’s wingtips. Rounded off at the front and back, the receivers have the same weight and center of gravity—but slightly higher drag—as the AIM-9 air-to-air missiles that Super Hornets carry there. Because its brawny electronics had to go somewhere, the ALQ-218 also robbed the Growler of its 20-millimeter Vulcan cannon. Still, the G carries air-to-surface missiles to take out radar dishes and other emitters, and air-to-air missiles to confront airborne threats.

With its wingtips occupied by the new antennas, the Growler still has nine external points for pods, fuel tanks, and missiles (see p. 44). The most recognizable payloads are the detachable ALQ-99 jammer pods, each with a ram air turbine, a passive mini-propeller on the nose of the unit that spins in the slipstream to generate its electricity. The innards of the 15-foot-long, canoe-shaped devices have been updated several times since their introduction. The pods limit the Growler’s speed, but chances are, with an active electronically scanned array (AESA) radar that reportedly can see 200-plus miles, the crew won’t get surprised by even a high-speed adversary.

The Growler hasn’t had time to compile a track record, and the Navy isn’t saying when it might deploy to Afghanistan. In one of the world’s poorest countries, where there are virtually no enemy missiles or anti-aircraft radars, the EA-18G might be a bit overqualified. But it can jam a Taliban cell phone call, or a signal from an electric garage-door opener intended to set off a roadside bomb. Some reports on the ground say that EA-6B Prowlers can now do “courtesy burns,” pre-flying the route of a truck convoy, emitting electrons all along to trigger buried explosives. The Navy offers no comment on such a capability.

Militaries sometimes tend to fight the last war, because it is the war they know. E-warfare is the realm in which they can least afford to do that. Yet, in times of relative peace, jamming advocates are forced to speak up to keep the funding flowing for research and development.

“Electronic warfare is something that everybody wants when you’re in combat, but nobody is willing to pay for in peacetime,” says Jack Dailey. “It’s extremely difficult to justify because it has to be based upon handling a threat that may not have been developed yet.”

The Navy has been sharing a few details about its Next Generation Jammer program, which will replace the ALQ-99 on the Growler at first, and then on the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter. Central to the jammer will be developments in AESA radars that promise much wider frequency coverage, better identification of sophisticated waveforms, and more seamless integration between the AESA and jammer.

And while it’s difficult to anticipate if the nemesis will be a cell phone or an advanced missile radar, one thing is for certain: the Navy will need the very best electronic countermeasures available to watch, listen, and act.

When D.C. Agle isn’t writing, he’s doing his best to refrain from growling as he changes his five-monthold twins’ diapers for the umpteenth time.