When NASA Told Its Astronauts to Quit Smoking

Even in 1959, it was considered bad for PR.

:focal(497x235:498x236)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7d/e7/7de790e5-6ebe-4500-b983-0f3810088ee0/apollo_and_soyuz_astronauts_backyard_party.jpg)

In the early days of NASA, no part of the American space program was more marketable than the astronauts themselves. The “Original Seven”—all military pilots ill-prepared for the harsh public spotlight—were introduced to the press on April 9, 1959 in Washington D.C. Even NASA was surprised by the intense response and enthusiasm of the press, and by their labeling of the astronauts as instant heroes. This decisive and dramatic moment is memorably captured in Tom Wolfe’s 1979 classic book The Right Stuff and the later film adaptation by Philip Kaufman.

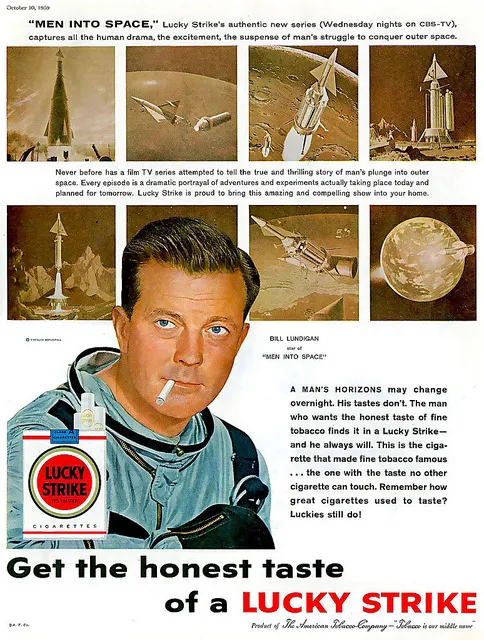

Yet 21st-century viewers of the press conference footage may be surprised by something Wolfe and Kaufman failed to record—the literal smoke-filled room. The original newsreel footage (see below) offers a time capsule of 1950s public behavior and a rare, brief glimpse of the human foibles of America’s new space heroes immediately before NASA attempted to mold their image. Six years after a widely reported study linking cigarette tar with cancers, the men who appeared on camera at the Dolley Madison House (there’s not a woman in sight) are casually smoking packs of cigarettes throughout the event—including the head of Project Mercury Robert R. Gilruth and Director of NASA Public Relations Walter T. Bonney. A 1957 Gallup poll revealed that a full 52% of American adult men were active smokers at the time.

Despite the general social acceptance of smoking in 1959, the fact that some of America’s new Mercury astronauts were smoking did not go unnoticed that day. One of the first questions fielded from the assembled journalists (at the 7:25 mark in the video) was prefaced by the observation that astronauts Deke Slayton, Alan Shepard and Wally Schirra were openly smoking at the front table. The bold reporter inquired if their habit might affect their future performance in the enclosed Mercury capsule. After some nervous laughter from the assembled department heads, Bonney asked for a show of hands from the actively smoking astronauts. The count was “three-and-a-half” with Scott Carpenter joining the earlier trio and a qualified interjection from Slayton that he was attempting to quit, thus accounting for the half.

After the 1959 press conference, NASA astronauts were rarely photographed smoking in public again. This was no accident. “Given the clean cut image NASA wanted to portray regarding its new Mercury seven astronauts, they were indeed asked by NASA to refrain from smoking in public,” according to Dee O’Hara, NASA’s nurse to the astronauts. Of the original Mercury Seven, only Gordon Cooper is believed to have been the lone nonsmoker. The others attempted to quit over the years, and all eventually succeeded except for Shepard, who lit up immediately prior to his Mercury flight. Even Schirra, who was photographed smoking during training for Apollo 7, eventually gave it up. As he wrote in his autobiography, Schirra’s Space:

I knew I had no choice but to quit smoking before the Apollo flight. To light up is to burn up in a pure oxygen atmosphere—it’s as simple as that. I had been trying to quit for ten years. In Mercury and Gemini I had put my hab it on hold for a day or so. So in January 1968 I began the painful process. I had been smoking OPCs (other peoples cigarettes) for a while. I put an end to that by giving everyone I’d mooched from a carton, and as I did I said to them: “Die!” It’s an effective way to quit—I never smoked again—and to terminate friendships.

In their new book Marketing the Moon, David Meerman Scott and Richard Jurek recount how NASA, private industry and the news media worked together to achieve a common goal: persuade the American taxpayer to spend nearly 4% of the national budget to send twelve Americans to the surface of the moon.