Where Did Max Miller Die?

One man’s search for the place where the U.S. Air Mail Service lost a star

:focal(2742x1571:2743x1572)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f2/61/f2619543-8677-48ab-9b7c-2baf25c443bb/15g_sep2015_si-85-6446_live.jpg)

I can tell you generally where it happened. An Air Mail Service pilot sent to investigate the crash telegraphed the assistant postmaster general: “Accident was on farm two miles southwest of Morristown, New Jersey.” Newspapers reported that on September 1, 1920, Max Miller, U.S. Air Mail Service Pilot #1, and his mechanic, Gustav Reierson, died “on the R.H. Thomas estate on the New Vernon Road.” The mail was gathered up, the crash site cleared, and Miller’s body buried in a Washington, D.C. cemetery less than two miles from where the National Postal Museum stands today, beneath a headstone carved with a U.S. airmail pilot’s wings.

But the ghost of Max Miller has brought me many hundreds of miles to a small hayfield near Morristown in leafy northwest New Jersey on an impossibly glorious Easter Saturday morning. Overhead are fluffy clouds, a deep blue sky, and an endless procession of aircraft, big and small, buzzing around airports in Newark and New York City to the east. This is rural New Jersey—horse country, old money, and big estates—but it must be one of the most continually overflown areas on Earth. Even in 1920, only two years after the Post Office started flying mail on a regular basis, locals had gotten used to constant overflights. Reporting the crash, the New York Times surmised, “So many planes have flown over Morristown since the route was established two years ago that the powerful metal ship would have attracted no attention had not its motor been backfiring with an ominous thundering noise.”

What caught the attention of the locals that September 1920 was the fiery plunge of what was then the most advanced civilian aircraft in the world. The Junkers-Larsen 6 was an all-metal monoplane designed in Germany under the careful direction of Hugo Junkers and assembled in the United States by industrialist John Larsen. Its cantilevered low wing and enclosed cabin fuselage, all sheathed in corrugated aluminum, were Junkers hallmarks. The JL-6 over Morristown was on fire, according to witnesses, losing altitude and shedding mailbags. The Times saw the dropped bags as proof of the Post Office pilot’s dedication: “Apparently seeing that he would be unable to bring his blazing plane out of its dangerous nose dive safely, Miller evidently had ordered his mechanician to release the stays that held the nine bags of registered mail so that the mail service might not suffer loss by their destruction.” The bags sailed free from the JL-6; the two men were in it when it hit.

I’m here in this sunny field this morning in what is now Harding Township, with a crew of undergrads from Professor Lee Slater’s Applied Environmental Geophysics class at the Newark campus of Rutgers University. With two graduate students, Gordon Osterman and Neil Terry, in charge, we are scanning this small field for the impact crater or any other distinctive soil disturbance that would mark the precise spot where the JL-6 went in—and where Miller and Reierson became numbers 15 and 16 of 43 U.S. Air Mail Service pilots, mechanics, and helpers who died delivering the mail between May 1918 and August 1927. Seven were killed in JL-6 crashes involving midair engine fires.

Standing with Osterman, I am watching undergraduate Andrew Lesende march downfield, tightly gripping a long white plastic pipe like a pole vaulter in slow motion. Inside the pipe is a sensor that captures small electromagnetic changes in soil composition, soil structure, and groundwater content. Lesende has to keep the pole parallel to the turf while staying on a grid line. Behind comes another undergrad, Carlos Fernández, pushing what seems to be a lawnmower but is in fact a heavy ground-penetrating radar unit. Another group is across Sand Spring Lane, a road that ends on James Street—once known as the New Vernon Road. There, Terry is organizing the other students to unravel the third technology of the day, an eight-channel “Super Sting” ERM, or electrical resistivity meter, which looks like a bright yellow clothesline of considerable length with large stainless steel clothespins to be driven into the ground at one-meter intervals. The clothesline will capture minute differences in resistivity (or its inverse, conductivity). Together, all three instruments may tell us what’s beneath our feet.

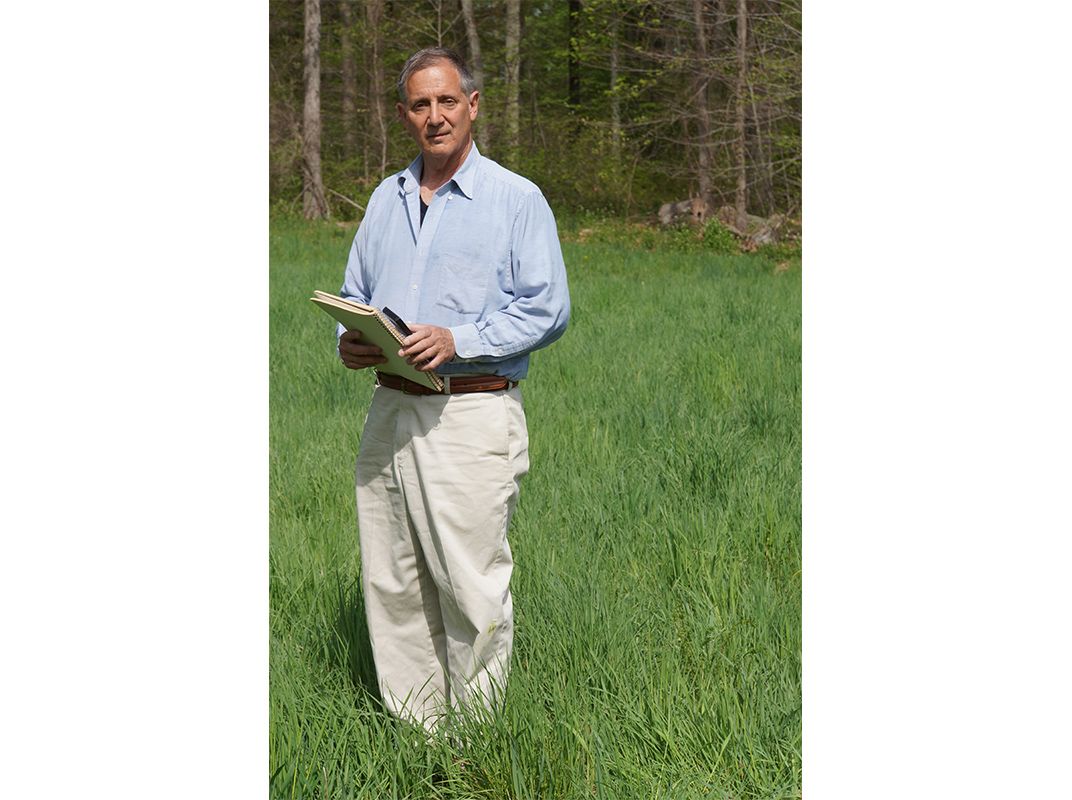

We are all here because of Robert Everest Johnson, a highly energetic electrical engineer who has worked in aerospace and telecommunications. Johnson became interested in Max Miller because of an earlier fascination with Harding Township. He doesn’t live here—he cheerfully admits he can’t afford it—but in Randolph, farther north in Morris County. But after Johnson and his wife joined a church in Harding Township, he began to soak up some of the area lore, including an episode in the history of aviation that, among airplane fans at least, put Harding Township on the map.

In the summer of 1966, two brothers from this town, Rinker and Kernahan Buck, 15 and 17, flew all the way across the country and back in a woefully underpowered and radio-less Piper Cub. Thirty-one years later, Rinker published a memoir of that summer: Flight of Passage. In it, he describes his difficult relationship with his father, a self-made publishing executive and one-time aerial barnstormer. (People who enjoy finding connections in the seemingly unconnected will appreciate the coincidence that this character, living under the flight path of the early airmail service, exhibits traits of both the daredevil pilots and the callous taskmasters who ordered them into the air regardless of weather.) Today Flight is something of a cult book, a secret handshake among those who like true stories, especially coming-of-age stories, about flying.

Johnson was so smitten with it that he wrote a screen treatment, which did not interest Rinker Buck, who had other fish to fry. But Johnson did manage to meet up online with Rinker’s older brother Kernahan, now a criminal defense attorney in the Boston area. When Johnson explained his interest in both Flight and Harding Township, Kern shot back with a challenge. “You live down there,” he said. “You might check this out.” What Kern wanted checked out was a memory from his high school years. It happens in the months before his cross-country adventure. He’s taking an older neighbor home—a fellow aviator—and just before they reach the intersection with James Street, the neighbor points out a field where a famous airmail pilot had crashed long ago.

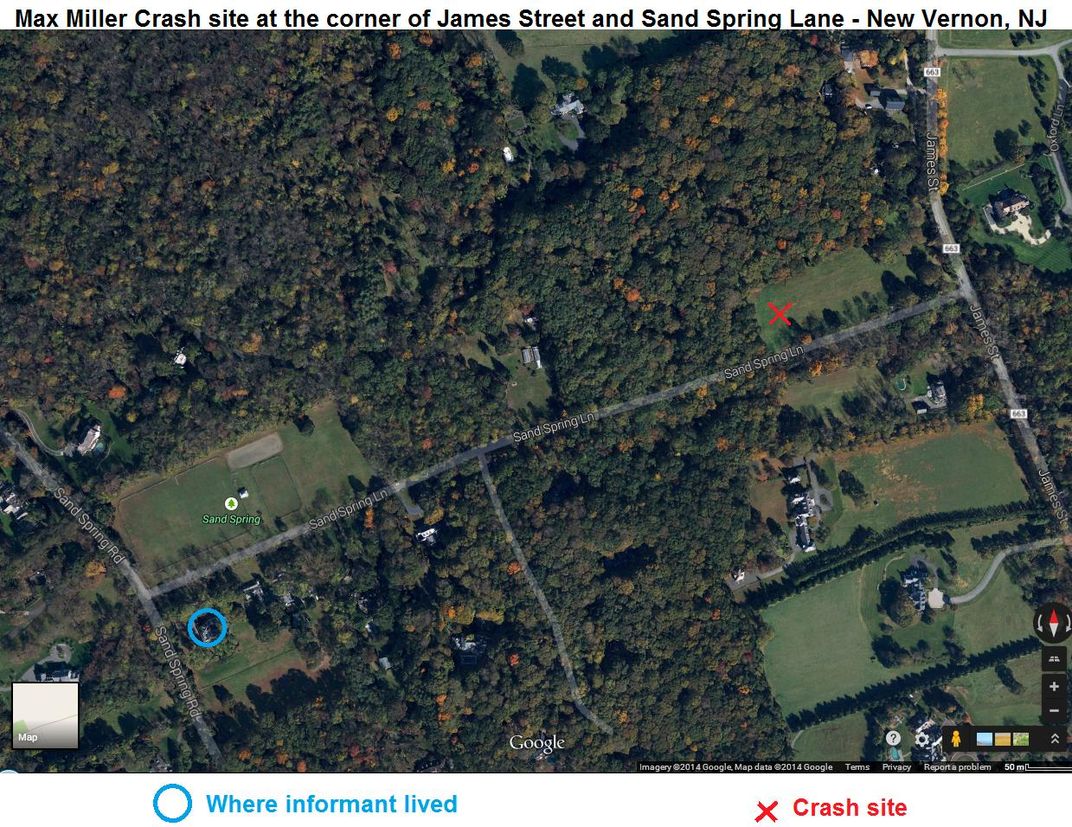

That memory came back to Kern Buck from another book, Mavericks of the Sky, a history of the early days of the airmail. Flipping through the index, he spotted Morristown, New Jersey, and was startled to find the Morristown Daily Record’s 1920 account of the death of Max Miller. Buck tracked down the original Record story, “Two Airmen Burned to Death When Mail Plane Fell on Thomas Estate.” The crash, the paper reported, took place, “on the R.H. Thomas estate on James Street.”

Was Max Miller the airmail pilot his neighbor had told him about?

The name, R.H. Thomas, was unfamiliar to Buck, who had known that area as the Frelinghuysen estate. “For 40 years, I had that memory that someone had told me that an airmail plane had crashed in the middle of the Frelinghuysens’ field on Sand Spring Lane,” he says. Congressman Rodney Frelinghuysen has represented New Jersey’s 11th District since 1995, but his family’s grip on New Jersey politics can be traced through a long line of “greats” to Frederick Frelinghuysen, who fought in the Revolution, served in the U.S. Senate, and helped draft the New Jersey state constitution. Was the 1920 Thomas estate the modern Frelinghuysen estate? Kern Buck asked Robert Johnson to find out.

With characteristic zeal, Johnson was soon turning up newspaper clippings, maps, and books about the Air Mail Service and its “fire proof” JL-6. On a 1939 plat map, he found the undated transfer of two large estate parcels from “Susie R.H. Thomas to Peter H.B. Frelinghuysen.” Sand Spring Lane had been named three years earlier, and it hasn’t changed. It’s a narrow, idyllic country road running between grand houses, woods, pastures, and fields. The hayfield Buck’s neighbor pointed to, with woods on two sides, was clearly shown. Peter H.B. Frelinghuysen was the father of current Congressman Frelinghuysen.

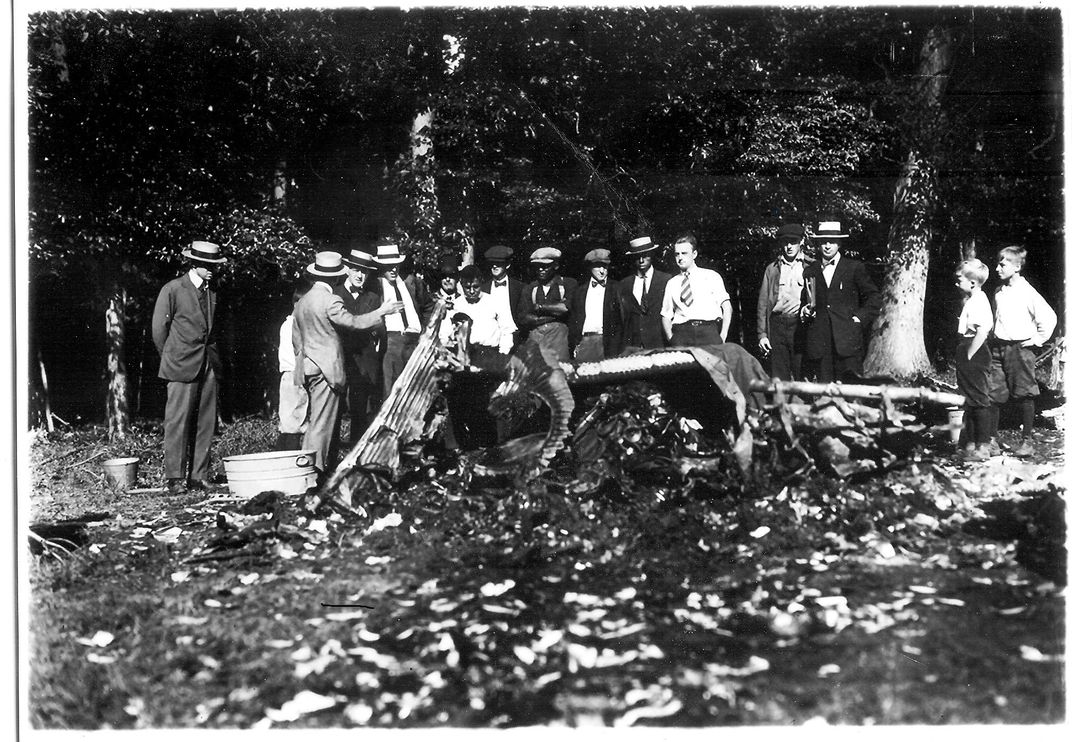

In the meantime, Kern Buck searched the Internet for “R.H. Thomas, New Vernon, NJ.” Up popped two photos from the Morristown Library of an airplane crash on September 1, 1920, taken by Frederick Venton Curtiss, a local freelance photographer who captured the wreckage and the crowds of curiosity (and souvenir) seekers. It is a warm sunny Wednesday. The men are in neckties and straw skimmers, the boys in knickerbocker breeches, and the women in ankle-length dresses and sun hats.

The testimony of Kern Buck’s neighbor combined with the property records and the photographs all point to the same hayfield on Sand Spring Lane. But when the neighbor was reporting the event to Buck, he was remembering something from almost 50 years earlier, and the photos of the field are close-ups nearly 100 years old. Don Jones, the author of the Max Miller biography Max, told me that he believes the airplane could well have come down on the other side of Sand Spring Lane.

Johnson thinks it’s important to find physical evidence. To research the farming history of the meadow, he tracked down the Frelinghuysen land manager, who told him that as far as he knew, the field in question was never plowed in the 20th century; it was left for hay. Johnson walked the field, discovering what he believed was a depression that exactly matched the upside-down radiator of a nose-diving JL-6. Reading about Rutgers University students who performed a geophysics survey for an archaeological dig, Johnson enlisted the volunteer services of the Rutgers Society of Exploration Geophysics, Student Chapter. When he called the Frelinghuysen estate office to ask permission for the surveyors to enter the field, he was told that the family had just donated it to a conservation trust controlled by Harding Township itself.

When Johnson started this quest, he did it, he says, because “it was fascinating to be involved with a project for no good reason.” Now, he says, “it has tremendously enriched my life,” and he’d like to see the story of Max Miller told to the widest possible audience, perhaps in the form of a historic marker, erected by the field, once the location is confirmed, as a fitting memorial to a pilot who had made an important contribution to the progress of U.S. aviation.

The Max Miller story is older than Harding Township, which was created in 1922 and named, by the township’s staunchly Republican voters, in honor of President Warren G. Harding. This might seem trivial except that Harding’s election in November 1920 may have been a factor in Miller’s fatal decision to press on with his flight to Chicago in a clearly faulty aircraft. Here’s how this part goes.

Eastbound from Cleveland in a JL-6 on August 25, 1920, Miller had made an emergency landing at Bellefonte, the Air Mail Service base in western Pennsylvania, with engine trouble caused by a “broken gas line between [fuel] pump and carburetor,” according to Miller’s handwritten report. After repairs were made, he took off but was forced down again at Lambertville in eastern New Jersey. Once again, Miller reported that the JL had a broken fuel line.

On September 1, Miller and his mechanic left Hazelhurst Field near Mineola, Long Island, at 5:30 a.m. in a JL-6. They came down in flames around 7:30 a.m. in New Vernon, a distance of roughly 40 miles by air. Where had they been for most of two hours? The most likely explanation was another forced landing and on-the-spot repair. And the most likely problem was the fuel line. It was the apparent cause of the two fatal crashes in JL-6s that followed Miller’s. Both of those aircraft experienced engine fires. So why would an experienced and level-headed flier like Miller press on in an aircraft that had already nearly killed him three times in four days? Politics.

The U.S. Air Mail Service was a creature of partisan politics. Second Assistant Postmaster Otto Praeger was a one-time Dallas newspaperman, a yellow dog Democrat, and an old Texas hunting buddy of Woodrow Wilson’s postmaster general, Albert Burleson. Given authority by Burleson to explore air delivery, Praeger got the Air Mail Service off the ground on May 15, 1918, using Army pilots and Army aircraft flying Washington-to-New York routes. But the service was erratic, non-competitive, and, according to Congressional Republicans, fueled by patronage. They were right. For the ruling party, the Post Office was a fountain of patronage—think of all those postmasters to appoint. The fountain still belonged to the Democrats in 1918, but with the upcoming 1920 elections, the Republicans hoped to sweep into the White House, take control of the House, and drastically shrink the federal government. Stop me if this sounds familiar.

Praeger quickly switched the airmail service to an all-civilian flying corps in June 1918, but he knew that the service was in a race against time and the Republicans. To hold off the budget cutters, Praeger had to establish a profitable, predictable, and rapid east-west service. New York to Chicago was his first goal. Then he would extend airmail, coast to coast. To do that, he needed pilots who would fly in all weather and in all kinds of machines. And Praeger and his deputies would not take no for an answer.

This was probably one reason Praeger hired Max Miller as the first civilian airmail pilot. Besides claiming 1,000 hours of flying time, Miller declared, “I have carefully considered the risks involved caused by bad weather conditions and I would be willing to do my best under those circumstances and would be ready to go out at any time required.” Praeger would test that willingness.

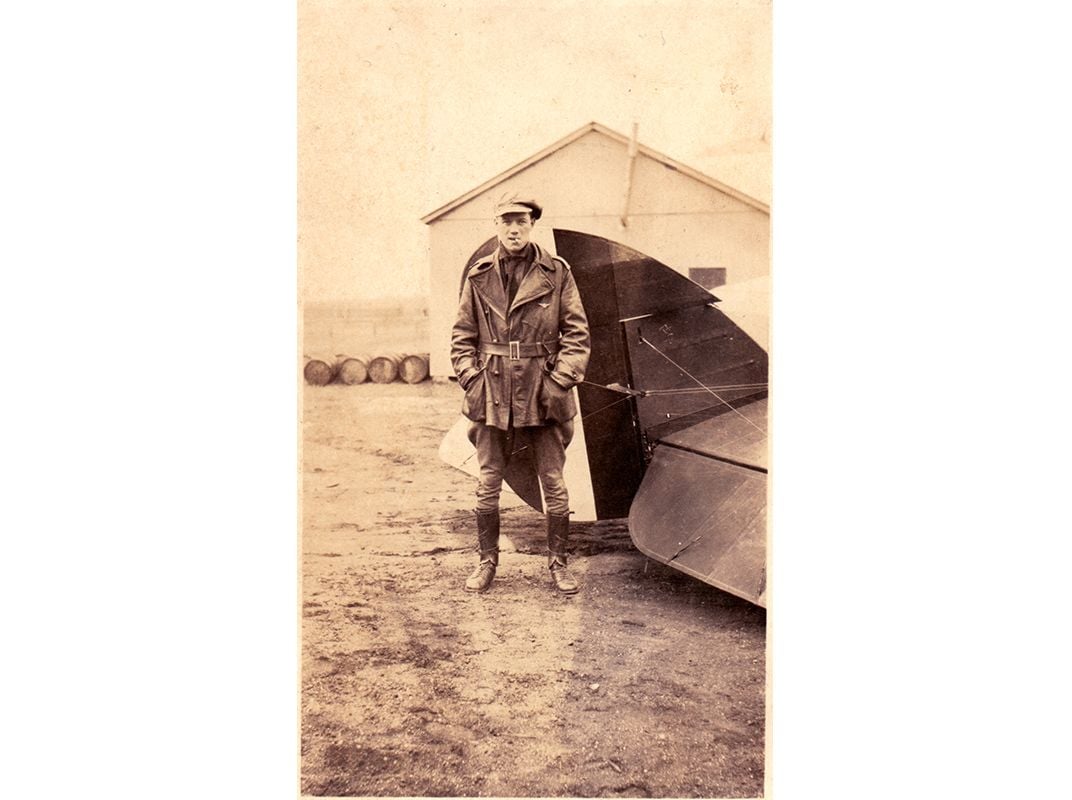

Max Miller comes with his own mysteries. He is amply documented in dozens of neatly typed Air Mail Service documents archived today at the Smithsonian’s National Postal Museum and nearby at the College Park Aviation Museum in Maryland. But his early life wasn’t really known until 2004 when A. D. “Don” Jones, a retired aerospace engineer and a leading airmail philatelist (stamp collector to you) published a biography of Miller for the American Air Mail Society. As a judge for international philately competitions, Jones was in Oslo, Norway, where he tracked down Miller’s niece and through her tapped into family documents and the Norwegian census. He learned that Max Ulf Moeller was born in Christiana (now Oslo) in 1893 (and not 1890 as he later told the Post Office), the son of a carpenter (and not a sea captain as he told his wife years later). The 1912 census reported that Max and his younger brother Ulf Moeller had migrated to the United States, probably in 1911. Max Moeller turned up as Max Miller in November, wearing the uniform of a U.S. Calvary trooper and assigned to Troop 6, 7th Cavalry in Luzon, the Philippines. He next turned up in photos as a machinist assigned to a U.S. Army aviation unit flying reconnaissance along the Mexican border in February 1913. There are no records of Miller going to flight school, but somehow he learned to fly. When his second Army enlistment ended in 1918, two officers stationed at the Rockwell Field, San Diego, testified to his good conduct and his experience as a “Flying Instructor at this school” with 725 hours and 56 minutes of flying time, all done during his Army career.

As a willing all-weather flier and an experienced mechanic, Miller became a pillar of the civilian Air Mail Service, flying regular routes in marginal conditions with unreliable aircraft guided by rudimentary instruments. The first pilot hired, Miller helped pioneer the “Woodrow Wilson Airway” from New York to Chicago, taking part in the hair-raising and highly publicized inauguration flight on September 5 to 6, 1918. Trapped above heavy clouds, Miller got lost repeatedly, developed a radiator leak, and was forced to land six times before reaching Cleveland. When Max finally landed at Grant Park in Chicago, he was nearly a day late. But he was greeted by a mob of postal officials, aviation dignitaries, and, of course, the press.

Miller, a tall, blond Scandinavian who was almost the prototype for Charles Lindbergh, was the service’s golden boy. Clad head to toe in leather flying gear, the handsome Miller looked like a movie star. Praeger certainly knew the value of good publicity; he sent Miller to a commercial studio for glamour portraits. When Miller married Praeger’s young and pretty secretary, Daisy Marie Thomas, the couple was photographed in the cockpit of an Air Mail Service airplane wearing matching helmets.

But Praeger rode Miller and all the service pilots hard, pushing them to fly even in dubious weather and combing through their accident, breakdown, and expense reports for evidence of shirking. On August 11, 1920, Miller got into a dispute with the superintendent of the New York to Chicago Division: He refused an order to fly one of the JL-6s just purchased by the service, and was terminated on the spot. Praeger reluctantly intervened by telegram. “The Dept. desires to retain Miller if possible, and consistent with discipline.”

Praeger’s iron-handed management style discouraged pilots from speaking freely about problems. You have to read closely between the lines of Miller’s August 16–20, 1920 report to Praeger to realize that the new JLs were dangerously slow and, if pushed hard, subject to violent vibration. Five days later, the fuel line troubles started. Seven days after that, Max Miller was dead. Two weeks later, on September 14, another Air Mail Service pilot and mechanic were killed in another JL-6 fiery crash. In the days before the Civil Aeronautics Act of 1938, the service did its own investigation. The engineering section concluded that the fuel line fittings were faulty. Modifications were made. The Air Mail Service declared the JL-6s airworthy.

On February 9, 1921, a JL-6 caught fire midair near LaCrosse, Wisconsin, and two service pilots and a mechanic were killed. The service finally had enough, and sold off its remaining Junkers monoplanes. (Ironically, the original Junkers design, the J-13, gained a reputation in Europe as the sturdiest of the early small civilian airliners. The J-13 was the founding aircraft of a number of European airlines and air routes; it stayed in production—with upgrades—until 1931. Professor Junkers always blamed his American importer, John Larsen, for unauthorized modifications to the JL-6s.)

Back in Washington in early 1921, Harding was preparing for his inauguration and the Republicans for their takeover of the House. The Air Mail Service seemed doomed. Then on February 22, 1921, a lame duck Praeger pulled off his Hail Mary play—a San Francisco-to-New York Air Mail transit of 33 hours and 21 minutes, 75 hours better than the fastest train record. A three-day jump on standard mail suddenly made airmail indispensable to West Coast banks and big businesses. When the Harding administration arrived in March, they made a clean sweep of Democratic appointees at the Post Office, but their Republican replacements kept the Air Mail Service going while Congress fumbled toward a transition to private contract carriers and the start of commercial airmail in 1925.

As airliners and the occasional prop plane sail overhead, I am standing in the hayfield with Gordon Osterman, listening to him describe his concern about the ground-penetrating radar. It doesn’t do well on soils with high clay content, which creates an electronic “ringing” that can blot out all other data. Unfortunately, says Osterman, this part of central New Jersey is underlain by the thick, high clay remains of a prehistoric glacial lake, known to geologists as Lake Passaic.

The other two technologies might have a better chance, he thinks. They might pick up traces of highly conductive metals driven into the ground or of disturbance patterns in tree roots. “Near-surface” geophysics, Osterman says, is concerned only with the top few meters of the earth. These techniques are used for plotting chemical spills, groundwater problems, lost graves, underground utilities, and archaeology sites. An airplane crash from almost 100 years ago is a different kind of problem.

To find physical evidence, the pole vaulter and the lawnmower keep pacing, but it’s soon clear that unrolling the yellow ERM line, driving the stakes, taking the measurements, and then uprooting the whole thing and resetting it five meters to the north is going to take far longer and wear out more people than expected. The undergrads all volunteered to perform this near-surface geophysical survey project and analyze the data for a group report instead of taking the final exam. At the start of the day, they were joking about finding an airplane wing. Many long hours later, they are debating whether the final exam might not have been the smarter choice.

The result of their hard work, the geophysical report, appeared weeks later and settled little. As Osterman and Terry feared, the ground-penetrating radar was a washout, the heavy clay soils turning the GPR signal from the lawnmower into meaningless ringing. The pole vaulter and the yellow clothes line did better. Between them, they mapped low-conductivity areas in the northwest corner of the field that suggest the aircraft crashed here, the force of the impact and the subsequent gasoline explosion leaving a compacted layer in the subsurface. In the end, though, the Rutgers team straddled the fence. “Ultimately,” wrote Osterman and Terry, “the data cannot be used to confirm the existence of a crash site, however it does not disprove such assertions either.”

Johnson’s documents and Buck’s vintage pictures make a compelling case that this field is where the airplane went down. The cause? The defective Junkers-Larsen fuel system, whether American-made or German mis-engineered. Preventable? Yes, Miller should have refused to fly a defective airplane, but for Air Mail Service pilots, the pressure to fly, no matter what, was relentless. Was the Air Mail Service worth it? Yes, although the lasting achievement was not the airmail itself but the invention of commercial aviation. From the early Air Mail Service came the beginnings of a sustainable transportation system that developed regulated maintenance, night flying, real-time weather reporting, better machines and better instuments, and even crash investigations. That list is a good start for any text that might go on a historic marker.

The Harding Township hayfield continues to hold mysteries. Robert Johnson would like to know where Miller and his mechanic went during the nearly two hours between takeoff from Long Island and the crash in New Jersey. Kern Buck wonders if Max Miller was trying to put out the engine fire by diving, an old-time pilot’s trick that Miller once employed to save himself over Pennsylvania. I want to know how so many stories could land in one meadow—daring Air Mail pilots, partisan politics, difficult fathers, serious geophysicists, a Norwegian cavalryman, and a “fire-proof” metal monoplane that fell burning from the sky.