Where Have All the Shuttle Engineers Gone?

To new jobs, some odder than others

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Shuttle-Engineers-631.jpg)

Michele Kocen is good at math. She is also very good at computer programming, trajectory analysis, and rendezvous navigation. Add these talents to her 25 years of experience in mission control at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas, and you have the ideal engineer for a human spaceflight program.

If you want to launch people—say, seven astronauts—in a reusable launch vehicle, Kocen is your gal. Her problem is the same one facing thousands of her former co-workers: Nobody does that anymore. Or at least, nobody does it in the United States or on the same scale that NASA did before the shutdown of the space shuttle program.

In the months leading up to the last shuttle flight in July 2011, NASA and its contractors shed workers at breakneck speed. Within a year of Atlantis’ final landing, United Space Alliance alone laid off more than 3,400 engineers.

So what’s a rocket scientist to do when there are no more rockets to launch? Some trade in rockets for airplanes. Others stay in the exploration business but look for oil instead of launch destinations. And a precious few—one, by my count—turn to hunting alligators.

Kocen decided to return to school. “My son and daughter were both in college, so it was funny having us all complain about professors and classes. But I love school and I’ve always had an interest in meteorology,” she says. Soon after leaving the space center, Kocen started taking classes at the University of Houston toward a master’s in atmospheric sciences.

“It was a few months after I got laid off that I was shopping for groceries in Galveston and I ran into an old friend,” says Kocen. “We’d known each other years ago through our kids, and it turned out that he’d become the manager in charge of the National Weather Service at Johnson Space Center. I mentioned to him that I was studying meteorology, so he told me he’d be in touch.”

Six months later, Kocen was back at the space center with her old badge in hand. “Two days a week, I go right back to the same building I’d worked at before. We do special forecasts for Johnson and Ellington Field—analyze National Weather Service maps and weather balloon launches out of Lake Charles [Louisiana] and Corpus Christi. Sometimes I get to use my old training when we’re listening in on the Orion vehicle status updates. They’ll say something about a desired trajectory and I’ll get to explain it to the weather people here.”

Being back at Johnson has also had its downside. “It can be awkward running into old friends in the hallways. They get excited and ask me how I got hired back and I have to tell them that I’m an unpaid intern this time around,” Kocen says.

For the former shuttle engineers, getting paid is a common problem. Eddy Solon was a shuttle reliability engineer at Kennedy Space Center in Florida. In the months after the shuttle program closed down, he started his own business. “We managed to get a contract after just a few months of writing proposals,” he says. “Our first one was with BAE [a British international military, security, and aerospace company], and I was thinking, This stuff is easy! It turned out that the contract never turned on. It just sat there.”

A few months later, his Space & Defense Engineering Services Company got another contract, this time from the U.S. Air Force, for replacing aging electronic parts on nuclear weapons. “Which was lucky,” he said, “because my wife was eight months pregnant at the time. We’d already exhausted our savings, so that contract couldn’t have come at a better time.” (Solon’s wife served as the company’s business manager.)

On the first day, Solon was giving an orientation program to a small cadre of engineers and support staff when the bank called. “They told us that they were pulling our loans. I asked them why and they said that the Air Force contract paid upon completion. We wouldn’t get a dime until the contract ended in six months.”

This kind of contract was news to Solon. “I didn’t understand how we were supposed to get a company up and running if we couldn’t get the money to pay our employees until after six months of work,” he says. Solon returned to his room of employees and explained the situation. “I emphasized that we’d still be getting paid, it would just be in one large installment instead of spread out over six months. I also said that if they wanted to leave now, I’d understand.”

Nobody left. For half a year, Solon’s employees worked without pay. He says: “That was a happy day when I got to call everybody back and tell them their checks came in.”

Lately, SPADESCO business has slowed. While they wait for contracts, Solon and his wife have started buying up houses to refurbish and resell.

Other former engineers started small businesses via less traditional routes. While working as a payload ground-handling engineer at Kennedy, Grayson Padrick had for years worked a second job: taking people out on the St. Johns River to hunt for alligators. “During the day, I’d be out at the launch pad getting payload into one of the orbiters, and then at night, I’d take a few clients out into the waters to hunt for gators. Every once in a while all of us from work would have a cookout and I’d be the one bringing a gator tail,” he recalls.

After the shuttle program shut down, Padrick worked on unmanned launch vehicles for a while, then decided to make his part-time gator business a full-time venture. “My dad was in the hotel business as I was growing up. And he also hunted gators. So I guess I learned both of those from him,” he says. “We started out with the hunting and soon expanded into gator processing, selling hides, selling tail meat to local restaurants.”

Padrick says he loves the night hunts the most: “We’ll be out there with the spotlight, just waiting to find a catch. Sometimes the conversation will turn to the space center and I’ll admit that I used to work on the space shuttle program. They get this shocked look on their face and I just tell them that I may be a redneck but even I used to have a day job.

“The hardest part sometimes is finding out how uninformed people are about our nation’s space program. When I tell them that I started the business after the space shuttle program got cancelled, some people tell me they didn’t realize the shuttles ever stopped flying.”

And some of what he learned during his years at NASA apply to his business today. “There was an amazing culture of safety at NASA,” says Padrick. “And I’d like to think I take some of that into the airboat with me. These can be dangerous animals. Our first move is to harpoon them and drag them into the boat. That’s 500 pounds of unhappiness and sharp teeth coming up at you, so you better believe that safety is paramount.”

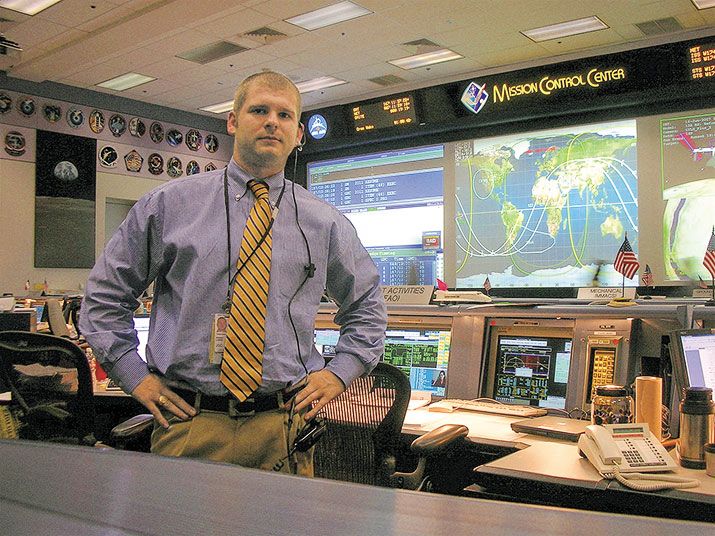

Beth Horner, a mechanical engineer who used to work at Johnson’s Mission Operations Directorate, saw the end coming but struggled with denial. “It was probably two months after they announced the layoffs that I started looking for work,” she says. “It was such a dream come true for me to work on the space shuttle program that it was hard to leave that.”

Horner found what many former JSC engineers have flocked to since the shuttles stopped flying. “Houston has two things, oil and space,” she says. Many former rocket scientists likewise shifted their attention to oil.

“My new company focuses on manufacturing pumps used in oil and gas extraction,” Horner explains. “When they drill holes down deep in the earth, there’s a lot of pressure down there. So there’s a lot of engineering and stress analysis that goes into manufacturing products that can deal with that environment.”

Horner says the atmosphere at her new place is totally different from that of her old place. “We were never supposed to touch anything at the space center—spacecraft are so sensitive and susceptible to damage. But here, we’re expected to go down on the shop floor and get our hands dirty.”

Despite NASA’s insistence that the manned space program isn’t on a permanent hiatus, Horner expresses the same fatalism many engineers feel. “I have a feeling that this change, this transition into a new industry, is permanent. It’s not that I’ve totally lost interest in what’s happening in the aerospace industry. I just have a feeling that I won’t be able to go back. That doesn’t mean I don’t still miss it.”

Perry Lewis, a former Johnson robotics flight controller, thought about where he might apply the skills he’d been using at NASA. “I used to talk with the astronauts, leading them through their on-orbit activities, so I concentrated on where I could use that ability to communicate effectively while still using my engineering skills,” he says.

Lewis came up with three industries that had a level of “operational complexity” similar to that of the space shuttle program: the military, the cruise-line business, and the airlines. “The military obviously requires a lot of logistics, but consider a single cruise ship: thousands of people, all requiring food, entertainment, travel arrangements. It must be an enormous operation. And of course, you can just look at your average airport to see the complexity involved in shuttling people around the country. These all present challenges that aren’t that different from doing an on-orbit repair.”

Today, you can find Lewis on the 27th floor of Willis Tower (formerly the Sears Tower) in Chicago, where he is an airline dispatcher. “I work in the Network Operations Center for United Airlines,” he says. “We run 6,000 flights every day, 40 to 60 of which come across my desk. I juggle weather, fuel, desired routes for all these flights, and use that information to release each flight.

“You have the pilot, the air traffic controller, and then you have me. Most people don’t realize my job even exists. But if you’ve ever been on a flight that’s set to leave and the pilot says he’s waiting for paperwork to clear before they can push back, that’s me. I’m that paperwork.”

Lewis says that working for United Airlines doesn’t have the kind of “wow” factor that working at Johnson did, “but this is about being happy. Working at JSC was the most incredible thing I could ever have imagined doing, but I came to the realization pretty quick that what all of us had come to love [the space shuttle program] was gone and it wasn’t coming back.”

Lewis’ friend Mike Bohac faced a similar realization at Johnson. He and Lewis had worked together on the shuttle remote manipulator system—the arm—but when the layoffs started, Bohac took his cues from his family’s history and his respect for the astronauts. “Many of my family members have served in our nation’s military, so that had always been a dream,” he says. “But while I was the primary mission designer for STS-129, I was impressed by the intelligence, cohesiveness, and professionalism of that astronaut crew.” What sealed the deal for Bohac was the fact that four of the seven members of the -129 crew had military backgrounds. He soon became a lieutenant in the U. S. Marine Corps.

“My peers [in the Corps] think I’m nuts for leaving the space shuttle program, or even NASA for that matter.” But serving in the military has been a dream come true, he says. “Going from being a provisional infantry rifle platoon commander to an artillery forward observer and just recently having the chance to serve as a 120-mm mortar platoon commander in the 24th Marine Expeditionary Unit has definitely been a wild ride!” he e-mailed from a Navy ship.

Perhaps no one has had a wilder ride—or at least supplied a wilder ride—than Helen Garcia. After working in the thermal protection system group at Kennedy, she was snapped up by Stewart-Haas Racing in Kannapolis, North Carolina. “They seemed really excited to have someone from the shuttle program,” she says. “Their public relations department interviewed me about my work on shuttle and they put me in their quarterly newsletter.”

The [racing] work was very fast-paced, says Garcia. “They would ask for a part on Friday, for example. And we’d design it, prototype it, build it, and test it in the wind tunnel to have it on the car and in the race on Sunday. The pace of approval for getting new parts designed was the absolute opposite of how things worked at the space center.”

Those first few months of long nights and hectic schedules paid off quickly. Garcia says: “My first year there, Tony Stewart won the Sprint Cup Series championship. It’s such a rare thing to win a championship, and I just happened to be in the right place at the right time. Tony ended up flying everybody out to Las Vegas on a charter flight. Each of us got to bring a guest and we all stayed at the MGM Grand. All on the company dime.”

Despite the perks of the job, the long hours and harsh winters (compared to Florida’s, at least) pushed Garcia elsewhere. She’s now back in Florida, helping design aircraft engines at Pratt & Whitney in West Palm Beach. Like many of her fellow rocket scientists, Garcia is still looking for that combination of exploration and awe that the shuttle program provided.

When the layoffs hit NASA and its contract companies in 2010 and 2011, some worried that the ensuing loss of institutional knowledge would make it difficult for the United States to mount another manned spaceflight program. Given how many workers have turned to ventures outside aerospace, those worries are probably well founded. But the skills required to launch humans into space are surprisingly similar to those used to drill for oil, or reroute flights, or win a NASCAR championship. Eddie Solon, the engineer who became a small-business owner, formed an online group called KSC Refugees. “A lot of us feel like refugees,” he says. “We’d like to think that some day there’ll be another program to work on. If it was something big, like the shuttle program, I know we’d all go back in a heartbeat.”

Jeremy Davis is a writer and engineer in Seattle.