Who Was Fatty Pearson?

A World War II British foot soldier’s best friend in the air, and the man who rescued Ernest Hemingway.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Fatty-Pearson-Peter-Briscoe-6-flash-631.jpg)

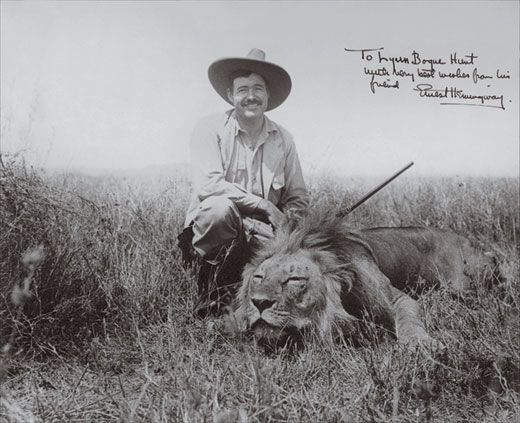

To know Fatty Pearson was to have a Fatty Pearson story. One yarn starts with an American hunter who had been lying on his cot for two long days, part of his intestine inflamed with dysentery. The year was 1934, and the African safari camp where the man was bedridden had no radio service. A guide set out to seek help.

On the third morning, a speck appeared in the sky. Fires were lit, and soon a little de Havilland Puss Moth had landed and was bumping along a strip of cleared savannah. It came to a stop, and out clambered Alexander Cuninghame—Fatty— Pearson, a burly young man with breezy, upper-crust English mannerisms.

The flight was unremarkable to Pearson. Still, he left an indelible impression on his ill passenger, 34-year-old writer Ernest Hemingway, and their hospital-bound flight would inspire the climax of the classic short story “The Snows of Kilimanjaro,” in which the pilot, Compton (“Compie”), appears as a figure of good-natured compassion.

The plane circled twice more, low this time, and then glided down and levelled off and landed smoothly and, coming walking toward him, was old Compton in slacks, a tweed jacket and a brown felt hat.

“What’s the matter, old cock?” Compton said.

“Bad leg,” he told him. “Will you have some breakfast?”

“Thanks. I’ll just have some tea. It’s the Puss Moth you know. I won’t be able to take the Memsahib [the protagonist’s wife]. There’s only room for one. Your lorry is on the way.”

Helen had taken Compton aside and was speaking to him. Compton came back more cheery than ever.

“We’ll get you right in,” he said. “I’ll be back for the Mem. Now I’m afraid I’ll have to stop at Arusha to refuel. We’d better get going.”

“What about the tea?”

“I don’t really care about it, you know.”

—“The Snows of Kilimanjaro”

The casual self-assurance that Hemingway glimpsed in Pearson served the pilot well over the 10,000 flight hours he logged. Many of those hours were in wartime Asian skies as the commander of the Royal Air Force’s pioneering special operations 194 Squadron. With insights gained from his bush piloting days in Africa, in which air service delivered with pinpoint precision could save lives, Pearson would help develop air-support tactics for modern military use.

What acquaintances remember most about Pearson was the force of his personality. After a 1984 London reunion of 194 Squadron members and Chindits—British army commandos—a member wrote in the squadron alumni newsletter: “Amidst all the talk, laughter and speeches, the invisible presence of the indomitable Fatty Pearson was almost tangible.”

Fatty had been dead for 40 years.

He came from Argentina, born of affluent British stock and well educated. Flying caught his fancy, and following the path of two brothers, Pearson enlisted in the Royal Air Force for pilot training and a five-year stint.

Out of the service in 1932, he found Africa one of the few places where a pilot could make a decent living during a global depression. His employer was Wilson Airways, a fledgling charter service that flew the 8A Puss Moth. A small fleet was housed in a corrugated-iron hangar in Nairobi, Kenya.

Just as the safari firms relied on the toughest vehicles—Chevrolets, Dodges, and Hudsons—and, for dangerous game, English-made double-barrel rifles, the charter services used the aircraft most suited to the job. The Puss Moth was a closed-cabin monoplane with enough range and reliability to be chosen for the first east-to-west solo crossing of the Atlantic, in 1932. In the bush, its tail-dragger design allowed pilots to steer on takeoff, with quick use of rudder and brakes, to avoid such sudden-appearing hazards as wandering zebras. Because the wings were above the cabin, the metal did not reflect up into the pilot’s eyes, and they allowed unobstructed scanning for landmarks or game.

In Africa, Pearson regarded himself as little more than a taxi driver, but the flying wasn’t always routine. The continent presented a steep learning curve. “MMBA”—miles and miles of bloody Africa—was broken by abrupt geological aberrations such as the Great Rift Valley, on the east. Downdrafts were sudden and unnerving. Maps were unreliable, and nearly all landings had to be made on soft surfaces of varying trustworthiness. Pearson mastered the terrain’s challenges, as Hemingway’s story shows.

The boys had picked up the cot and carried it around the green tents and down along the rock and out onto the plain…to the little plane. It was difficult getting him in, but once in he lay back in the leather seat, and the leg was stuck straight out to one side of the seat where Compton sat. Compton started the motor and got in. He waved to Helen and to the boys and, as the clatter moved into the old familiar roar, they swung around with Compie watching for warthog holes and roared, bumping, along the stretch between the fires and with the last bump rose and he saw them all standing below, waving….

With his confident, sunny nature, Pearson was a good fit for safari work, “a terrific personality,” recalled hunter Romulus Kleen in Bror Blixen: The Africa Letters. He could easily hold his own in conversation with celebrity clients, ranging from Hollywood royalty to actual monarchs. Yet he was no snob—a good thing in the logistically demanding safari trade, in which teamwork with everyone, down to the lowliest cookboy, was essential. (I speak from personal experience: I was born in 1949 and grew up in Nairobi—our neighborhood bordered Wilson Airport, Pearson’s old base—and was no stranger to safari travails.) Fatty’s RAF ratings to fly multi-engine airplanes helped make him the right man at the right time. As head pilot, he was part of Wilson Airways’ ambition to be a scheduled mail and passenger carrier.

Wilson attracted Britain’s Imperial Airways as a shareholder. The fresh capital paid for eight twin-engine de Havilland Dragons. These included an advanced variant, the eight-passenger D.H.89 Dragon Rapide, whose elliptical wings and streamlined silhouette are familiar from old travel posters. Unadvertised to would-be tourists were stomach-churning thermals and hot, stuffy cabins.

We can picture what it was like on a flight from Europe down to Nairobi from a letter written by Pearson’s pal, professional hunter Bror Blixen. They were the only two aboard; Pearson was probably delivering the Rapide, while Blixen, a native Swede, was hitching a ride. The two friends had much in common, including reputations as bons vivants.

They crossed the Libyan coastline and landed at a village. Though the sun was setting, they decided to press east along the coast to Mersa Matruh in Egypt, which had accommodations. Fifteen minutes later, all was dark except a white line of surf. Then they saw the lights of Mersa Matruh. They circled low in hope of getting someone out to the airfield to light it up. No one did.

Guessing that a certain dark patch was the field, Pearson landed blindly, braked hard, and discovered that he had stopped five yards from the hangar’s door.

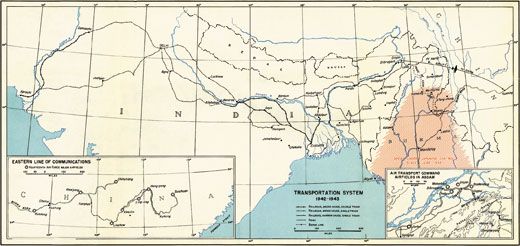

Another night dark beyond belief: monsoon season, 1943. Again, he was at the controls, again a good friend beside him: Wilfrid Russell. This time, Pearson was flying for the RAF; Russell, who recalled the incident later in his book Forgotten Skies, was a fellow wing commander. The usual occupant of the copilot’s seat, Pearson’s bull terrier, Sue, had been assigned to the rear with the only other human passenger, Russell’s terrified aide. No navigator. Their C-47, the military transport version of the Douglas DC-3, was deadheading back to India after delivering troops in Burma.

Below the aircraft, the Himalayan foothills climbed to 8,000 feet; ahead, also unseen, monsoon cumulus towered to 20,000 feet. Pearson’s attempts to skirt the massive cloud bank failed. Rain hammered on metal; lightning boomed.

“Whizzo,” said Pearson, impressed.

They reversed course and tried to outrace the front. The buffeting eased when gaps developed between the thunderheads, allowing the moon to appear for a second or two. But where had the storm blown them? Pearson banked and looked down. Finally: a glint. He dove, and there it was, the only lake within hundreds of miles. With that bearing, they thundered up a valley to a covert airstrip, fired down a flare, and in its illumination, landed, in Russell’s words, “as gently as a kiss.”

By then, Pearson could fly just about anything. On top of his bush piloting skills, he had flown Imperial’s lumbering intercontinental behemoths and, with the outbreak of war, served as a test pilot in Pakistan, flying a wide variety of RAF aircraft. One day, Russell recalled, after a Supermarine Spitfire landed in Pakistan, Pearson’s flight sergeant asked if Pearson had ever flown one. No, never even seen one before. Had he flown any single-engine fighter? No, but he would like to; would anyone mind if he certified it for service? No one did, so, squeezing his six-foot-one, 235-pound bulk into the cockpit, Fatty took the Spitfire up and gave it “20 minutes of outstanding aerobatics.”

Soon, Pearson was leading a photo-reconnaissance squadron that shadowed the Japanese advance in eastern Asia. The sight of him bouncing up and down to settle his bulk into the seat of a Hawker Hurricane, only slightly bigger than a Spitfire, regularly drew a small crowd of marveling airmen. Still, it wasn’t Pearson’s size but his charisma that was described when a wartime writer, watching him deplane at a badly shot-up airfield, said that it was “like seeing the Rock of Gibraltar get out.”

He was promoted to commander of 31 Squadron, which used transports to make air drops behind enemy lines. Then in the autumn of 1943, he moved to the 194. Pearson had pull at the RAF’s New Delhi headquarters, which enabled him to reshape 194, transforming it from a courier squadron into his own creation: a unit that would provide full-service support for the troops fighting below. After selecting its key officers from his old squadrons, he came up with its nickname, the Friendly Firm, and its nose-art insignia, a Dumbo-like flying elephant.

The concept: an air squadron that would help you out no matter where on the ground you were or what condition you were in. No longer did wounded men have to die in the jungle, “rotting under a tree,” as one soldier put it. A trusting C-47 crew, landing on a strip the commandos had cleared on a plateau and marked “Land here” with parachute silk, evacuated wounded Chindits to medical facilities. A Life magazine photographer was aboard that airplane. His photographs of the Chindits, picked up within 14 miles of a Japanese air base, show men so haggard and hollow-eyed they look like ghosts. Yet all have wide smiles.

A division of Chindits, including the Gurkha troops from India, was scattered around the jungle, waging a series of savage campaigns that disrupted Japanese supply lines and captured air bases. By late 1943, the Allies were gaining control of the skies. With the C-47s at their call, “the British and Indian soldiers knew that being surrounded and apparently cut off meant nothing if you had air power and air superiority,” Russell writes in his book.

Aerial ground support techniques were developed, and training was intense. Some radio operators in 194 Squadron learned to parachute down from a mere 700 feet, with Fatty there to congratulate the volunteers after their practice jumps. Since full-service support now included not only pinpoint relief operations but also, when needed, troop airlifts, ground crews focused on off-loading four tons of cargo in minutes.

In the spring of 1944, for the first time ever, an entire division and its gear were airlifted directly to the battlefield, with the C-47s of 194 flying 758 sorties and U.S. aircraft flying others to the strategic town of Imphal. That monster battle, lasting four months, relieved the siege there and marked the greatest defeat of Japan’s Imperial Army to date.

Under Pearson’s command, during the big offensives of 1943 and 1944, crews flew multiple times around the clock, with much of the flying low-level and stressful. Downdrafts could require the full strength of the pilot and sometimes a second man to regain control. Sweating crews flew shirtless; in May, as the monsoon season started, they confronted surprise icing.

Despite the arduous conditions, only three of 194’s airplanes were lost.

On the plains of India, the heat could top 100 degrees Fahrenheit. Without shade, the metal could get hot enough to cause severe burns, and it wasn’t always possible to work on the airplanes at night. Pearson had giant scaffolds with thatched coverings erected to shade the work. “Is it any wonder the ground crews held him in high regard and gave such loyalty,” former 194 navigator Peter Briscoe wrote me. (Briscoe is Canadian, as were many of Pearson’s men.)

Empathy with the lower ranks was not an RAF tradition. At other squadrons, non-commissioned pilots felt like second class citizens. But at the Friendly Firm, sergeant pilots such as D.W. Groocock were warmly welcomed by Pearson and assured that those who did their jobs would soon be officers. “In a few days time,” Groocock wrote me, “I found that Fatty’s personality and attitude permeated the whole squadron.”

That was vital. The ability to drop supplies for an entire battalion within a 100-yard circle in a wilderness clearing 200 miles behind enemy lines was a feat that took the full effort of all ranks. Pearson’s consideration for all his men—ground crew, loadmasters, and pilots—instilled in them “a desire never to let him down,” Groocock said.

Pearson’s care also extended to U.S. crews, whose lives would depend, for example, on his flares lighting up covert strips during the monsoon storms. Pearson and the Chindits got a powerful comrade in arms: U.S. Army Air Forces Lieutenant Colonel Philip Cochran, whose First Air Commando Unit took Pearson’s concept of full-service support and ran with it. The unit pioneered its own unconventional tactics for jungle drops, some of which involved, for the first time in combat, helicopters (194 Squadron didn’t get helicopters until the early 1950s).

Cochran was short and trim, but otherwise shared several traits with Pearson, including a sense of humor, and the two got along well. Their leadership resulted in medals for each from both countries; Pearson’s included the American and British Distinguished Flying Crosses. And, like Pearson, Cochran was the inspiration for a fictional character: Flip Corkin in the popular comic strip “Terry and the Pirates.”

In 1944, during a break from combat, Pearson was posted as chief flying instructor at a base in rural England. On November 29, before his scheduled reposting to lead a bomber squadron, he flew down to the Biggin Hill air base, outside London, to lunch with his brother Herbert, now Air Commodore Pearson, and old chums from the Far East.

It’s possible alcohol was consumed by a pilot who, after all, had been known to uncork sherry in flight, all the better to enjoy the view of the Himalayas. At any rate, when Pearson left the officers’ mess hall, he wasn’t attentive, and, before the Dakota’s engines even started, he made an elementary mistake. According to the RAF accident report: “Prior to T.O. [takeoff] assistance from ground crew was declined. Pilot failed to remove elevator lock.” This device stabilized the starboard elevator while the airplane was parked, so when Pearson took off, a key control was frozen. He managed to circle twice, then tried a wheels-up landing, engines still running. A wing clipped the ground, and the prop sliced through the cockpit, killing Pearson instantly. His navigator was slightly injured.

Fatty Pearson was deeply mourned within the RAF. His name was inscribed in the chapel at Biggin Hill, along with those who had died flying out of the field earlier in the war. He is buried in a nearby cemetery shaded by giant yews.

Then they were over the first hills and the wildebeeste were trailing up them, and then they were over mountains with sudden depths of green-rising forest and the solid bamboo slopes, and then the heavy forest again, sculptured into peaks and hollows until they crossed, and hills sloped down and then another plain, hot now, and purple brown, bumpy with heat and Compie looking back to see how he was riding.

Tim Belknap's journalism career has included long tenures at the Detroit Free Press and Business Week. He is the son of a World War II veteran who, in the jungles of Burma, was one of the grateful recipients of a supply drop by Royal Air Force Squadron 31.