Was the FBI Right to Hound One of America’s Foremost Rocket Pioneers?

A new book examines the controversial life of Frank Malina, who co-founded the Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

:focal(622x228:623x229)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f6/0b/f60bbe34-a007-4d36-b00c-12185397cb85/malina.jpg)

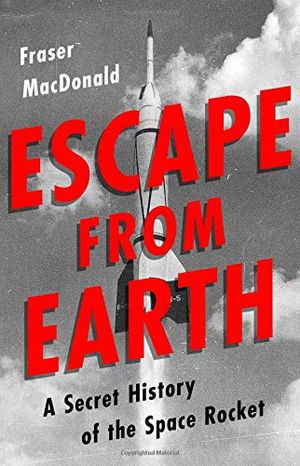

Fraser MacDonald, a writer and a lecturer in human geography at the University of Edinburgh, is the author of Escape From Earth: A Secret History of the Space Rocket, a new book that illuminates the life of Frank Malina, co-founder of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. Though Malina was an accomplished scientist who made significant contributions to the field of rocketry in the 1930s and ’40s, he remains a relatively obscure figure in the history of aerospace. MacDonald’s thorough book explains why he isn’t better known. He spoke with Air & Space senior associate editor Diane Tedeschi in August.

What compelled you to research the story of Frank Malina?

He is America’s first successful rocketeer—the person who made rocketry scientifically respectable. Yet, weirdly, he has only ever been a bit-part player in other people’s histories. A book about Malina is long overdue, not just because of his historic significance, but because his story is so full of intrigue, tragedy, and improbable good fortune.

Malina invented jet-assisted takeoff (JATO) and the WAC Corporal, the first sounding rocket developed in the United States. He also co-founded JPL and Aerojet. Do you think his accomplishments merit broader recognition?

Absolutely. Aside from his institutional legacies, many of his technical contributions have largely gone unnoticed: from hypergolic liquid propellants to the theory of long-duration solid propellants. He also helped develop the political infrastructure of space exploration: the International Academy of Astronautics, for example.

Why isn’t Malina more well-known?

I don’t think it’s a conservative conspiracy, but politics does play a role. There’s been a cloud over Malina’s reputation for years. I think people have long suspected that he was a communist, and now the rumors of his party membership turn out to be true.

All of this has meant that Malina has not been an easy figure to celebrate, especially in anti-communist times. It also didn’t help that he left the United States, and left practical rocketry, by the time that some of the most charismatic advances into space were being made.

Do you think the FBI’s investigation of Malina was warranted?

Actually, I do—though I didn’t at the beginning. I saw things rather differently by the end of the book. That doesn’t mean that the FBI investigation of Malina was fair—it often wasn’t—but he was a member of the communist party at a time when the party was routinely used as a front for intelligence operations. He must have known that being a communist working in classified defense research would attract some scrutiny.

Did Malina feel a sense of loyalty to the United States?

He was loyal. The complication is that he didn’t put much store by nationhood or sovereignty—his own or anyone else’s. Malina was internationalist to his core. The problem was that some of his colleagues thought this aversion to flag-waving meant that Malina might be a Soviet agent. Malina’s successor as director of JPL, Louis Dunn, made unfounded accusations of espionage, which sparked off a sprawling campaign against JPL’s left-leaning engineers.

Was Malina comfortable accepting military contracts?

At the beginning, I’d say he was sanguine rather than comfortable. He told himself that rockets might be needed to fight fascism. But he was deeply unhappy at the prospect of his Corporal missile becoming the bearer of a nuclear warhead. He started to have panic attacks in meetings. He even sought help from a psychoanalyst—not realizing of course that his analyst was all along working for the FBI.

Did Malina ever cross paths with German rocket scientist Wernher von Braun?

As far as I know they met only once, at the 1965 International Astronautical Congress in Athens. I suspect Malina tried to avoid meeting him: He hated everything von Braun stood for. It made Malina queasy to think that engineers who had worked for the Nazi Party and the SS could be brought into the heart of the American space establishment—while campaigning anti-racists were left out in the cold.

What would you like people to know about Malina?

He was an ordinary person who made extraordinary advances in our journey to space. Malina was an anti-fascist and anti-racist. He took the risk of fighting for the political change that he believed was important. In the end, this cost him dearly. His friends had it even worse: They faced jail, deportation, blacklisting, and suicide. Frank Malina was ultimately someone who felt that transforming the Earth was more important than transcending it.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.