Why Alan Shepard Carried a Dollar Bill on His Mercury Flight

A new meaning for the old expression, “No bucks, no Buck Rogers.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/50/a7/50a7c2b2-0244-44e4-91ac-0904009c976a/shepard_on_deck.jpg)

Shortly before Alan Shepard became the first American in space on May 5, 1961, officials at NASA and the U.S. National Aeronautic Association (NAA) found themselves in a quandary. In the three weeks since Yuri Gagarin’s April 12th first spaceflight, a tempest-in-a-teacup had erupted over how that historic event should be certified. The Soviet Union was vigorously seeking official recognition from the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale, a Paris-based organization that has validated global aeronautical records in cooperation with national organizations like the NAA since 1905.

But the FAI had strict rules about certifying world records—including requiring witnesses.

“Many details of [Gagarin’s] flight still have not been made public,” wrote W.B. Ragsdale for the Associated Press after the Vostok 1 mission. “Russian officials had not yet produced any of the documentation mandated by the FAI.” The association gave the Soviets a deadline of August 12 to file the appropriate proof, which they eventually did. But at the time of Shepard’s flight, official recognition was still being withheld, and NASA officials didn’t want to risk the same PR speedbump.

According to the FAI’s “code of conduct,” an NAA official would need to witness and verify that the person who stepped into the Mercury capsule at Cape Canaveral was indeed the same person who exited the capsule 100 miles downrange in the Atlantic Ocean. The problem? It was only a 15-minute flight. There would not be enough time for the NAA official to get from the launch site to the splashdown site.

Working behind the scenes, NAA and NASA officials came up with a simple but elegant solution. As detailed by Frank Macomber for Copley News Service in a 1971 news wire article titled “Astronauts and the Record Book,” Shepard would carry a dollar bill aboard Freedom 7 given to him by an NAA witnessing official. Later, after recovery in the Atlantic, Shepard would produce the bill. The serial number would be transmitted via radio and compared with the number recorded by the NAA observer. A match would be accepted as formal verification.

The FAI agreed, and this became standard practice on the first U.S. spaceflights.

“If all of this rigamarole seems a little ridiculous, the same procedure has been followed on every U.S. space mission—Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo,” Macomber wrote 10 years after Shepard’s flight. “The dollar bill fulfills the identification requirement of the FAI Sporting Code, even though modern telemetering equipment and worldwide television now effectively remove any doubt as to the astronaut identity.”

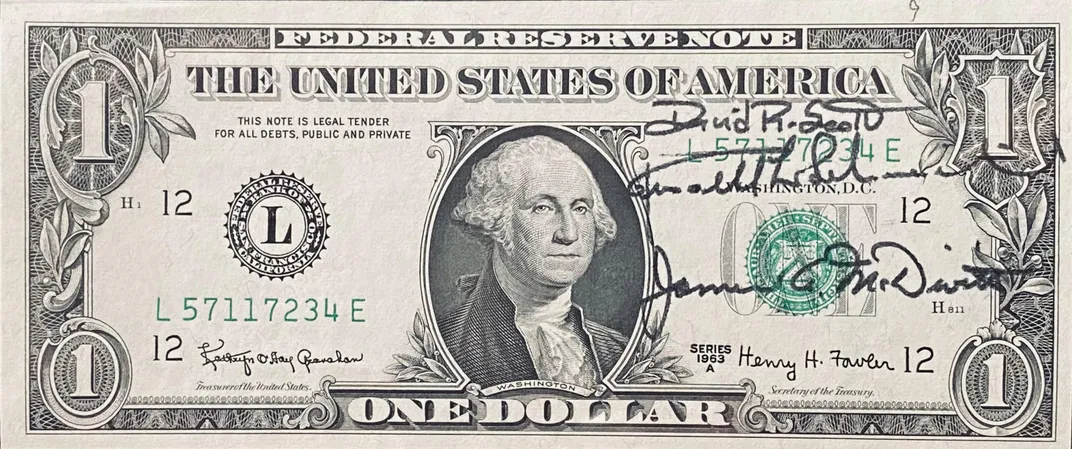

On the longer-duration flights that followed Mercury-Redstone 3, the same NAA official who supplied the dollar bill was flown to the recovery carrier, where a formal certification ceremony took place. Often, the official gave the astronauts extra bills to give out as souvenirs. At the shipboard ceremony, with the assembled press pool watching, the astronauts would autograph the flown bills in front of a witnessing NAA official.

Occasionally, as in the case of Walter E. Wentz of Pasadena, California, these officials became minor celebrities themselves. In August 1965, photos from the Gemini 5 certification ceremony aboard the USS Lake Champlain received wide media attention. Dubbed an “international referee” in the photo caption, Wentz was even invited to appear on the popular To Tell the Truth television quiz show.

Altogether, the FAI has certified 217 individual space flight records since Gagarin’s in 1961. They cover a range of categories, including distance, speed, total mass lifted into space and flight duration. NASA ended the practice of carrying dollar bills after the flight of Apollo 17 in December 1972, partly due to a minor scandal over Apollo 15 astronauts carrying postal covers into space. During the Skylab era of the 1970s, stylized NASA paper certificates designed by the Johnson Space Center and the NAA were used instead of money, as they were believed to have less commercial appeal. To this date, NASA astronauts are prohibited from carrying currency of any kind into space as a personal souvenir or memento.

The historic nature of the space-flown dollars was not lost on NASA or the National Air and Space Museum, however. Shortly after Apollo 17, Marvin L. McNickle, an official in the agency’s space transportation office, wrote to Frederick Durant, the Museum’s Assistant Director for Astronautics, to say that NASA was in possession of the Apollo 17 bills and that the Museum would be a more appropriate place for them since “these bills now, individually, have considerable historic significance and intrinsic value.”

Even though, according to McNickle, bills from Mercury, Gemini and the earliest Apollo flights were the private property of the NAA witnessing officials, the NAA kept possession of 22 dollar bills used to certify the flights of Apollo 7 through Apollo 16, including four each from Apollos 11, 12, 15, and 16. NAA Executive Director Brooke Allen agreed to NASA’s request to turn them over to the Museum.

On December 29, 1976, the bills were officially donated, and they are now part of the Museum’s Social and Cultural Space Collection in Washington, D. C. While not currently on display, some of the bills appear virtually on the Museum’s website. And while they were intended to mark the historic nature of the first U.S. spaceflights, they also made George Washington—or at least his likeness—an unlikely astronaut. Ad Astra, George.