Wilbur Wright and the Statue of Liberty

Ten years of research leads to a painting.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/In-the-Museum-UntoldHistory-3-715.jpg)

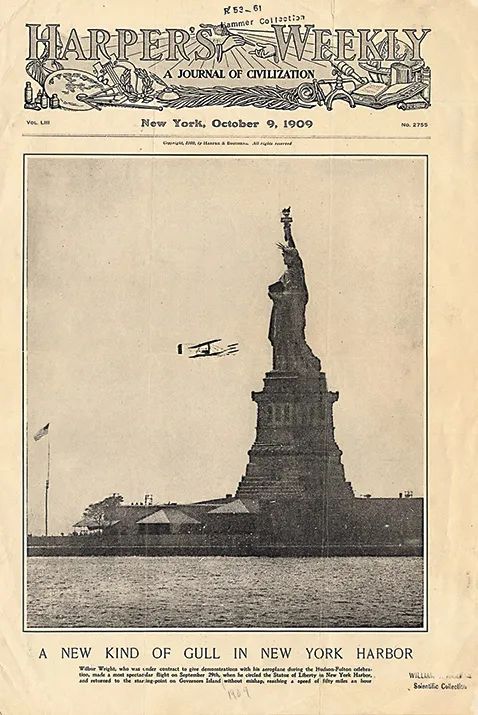

In 2002, when I first learned of Wilbur Wright’s 1909 flight around the Statue of Liberty, I knew I wanted to paint the scene. It would take 10 years of research, and I would end up building two models of the Flyer and its controls before I felt able to capture the moment on canvas. By the time I started my painting, which was recently accepted into the National Air and Space Museum’s collection, I’d learned the full story behind that historic flight.

Wilbur Wright had a lot on his mind when he arrived in New York City on September 20, 1909. With him was his mechanic, Charlie Taylor, and a Flyer still crated and ready for assembly. For a celebration honoring the maritime achievements of Henry Hudson and Robert Fulton, Wright had agreed that sometime between September 25 and October 9, he would make a flight that was either at least 10 miles or one hour in duration. In exchange, the city would pay him $15,000. What worried Wilbur that day was that his flights would be over water.

Just a few months earlier, when Wilbur was seriously considering attempting the first airplane crossing of the English Channel, Orville had written him to discourage the flight. The brothers’ greatest concern was engine reliability. Wilbur knew that if the engine failed and he had to set down, his skids would bite into the water, throwing him forward into the wires crisscrossing between the forward struts and possibly injuring him. As the wood-and-cloth wings would begin to settle and sink under the weight of the engine, they could drag him down before he could disentangle himself.

So when Wilbur arrived on Governors Island, south of Manhattan, on the morning of September 29, he and Taylor had made a strange modification to the Flyer: Beneath the lower wing, they had slung a bright red canoe, which Wilbur had purchased a few days earlier from the H&D Folsom Arms Company. A top-of-the-line Indian Girl canoe made by the Rushton Canoe Company, it featured a sturdy 16-foot frame made of northern white cedar, which Rushton claimed was nearly a third lighter than other cedars.

The canoe’s light weight (approximately 60 pounds) and sturdy construction attracted mostly Adirondack hunters and anglers used to portaging around rapids and waterfalls. Wright was drawn not only by these features but also by the canoe’s aerodynamic shape.To reduce drag, Wilbur had removed the Flyer’s second passenger seatback, and for waterproofing had tightly sealed the open canoe top with nailed-down canvas.

In essence, the canoe turned the Flyer into the world’s first floatplane. Wilbur hoped that in the event the engine failed and the airplane ended up in the water, the canoe would keep the aircraft afloat. With luck, as the airplane glided into the water, the canoe might even hold the craft upright. As the airplane floated, the pilot would have time to extricate himself and swim away. The addition of a life vest next to him, which he could don before swimming clear, suggests that Wilbur had characteristically thought the matter through and come up with a contingency plan.

The Wrights were used to firsts, and this was the first time a pilot would be carrying a large object aloft, so the arrangement needed to be tested for stability. At 9:15 a.m. on September 29 Wilbur ran down the rail built to assist takeoff, positioned into the light westerly breeze, went airborne, made a two-mile flight around the island, and landed safely. Satisfied that the canoe would not impede his ability to control the Flyer, he announced that he would fly again.

At 10:17 a.m., he arose from the rail, which was still oriented into the light west wind, and flew due east. A man in the crowd exclaimed, “I believe he’s off for Philadelphia!” Charlie Taylor calmly corrected him: “No, he will round the Statue of Liberty.”

And so he did. Crossing between Ellis and Liberty islands, Wilbur steadily gained altitude, then began a turn to the left, closing the distance to Lady Liberty. At 10:20 a.m., at an altitude of 200 feet, he passed in front of the statue, his wingtips only a few hundred feet from her waist.

He then flew back to Governors Island and landed at 10:22, in view of several hundred thousand spectators in lower Manhattan and the delighted passengers crowding the deck of the outbound Lusitania. On October 4 he would fulfill his contract by flying a distance of more than 20 miles in 33 minutes and 33 seconds.