Where the Wild West Meets the Cosmos

On the far side of Edwards Air Force Base, a quirky museum of flight.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/09/c2/09c260f6-d951-4fb7-b6d1-408ba9f127b0/03g_am2018_boronsign_live.jpg)

The Feds descended on Boron, a small desert town not far from the site where Chuck Yeager broke the sound barrier, in a platoon of ominous black SUVs. They were looking not for drugs or terrorists but for a trio of LR-89 rocket motors, originally affixed to Thor missiles, and an LR-105 that had once been the heart of an Atlas launcher.

The rocket motors were in the collection of the Colonel Vernon P. Saxon Jr. Aerospace Museum, a tiny tourist attraction in the California town, population 2,253, best known as the world’s largest producer of borax. (Borax is often used in laundry products and was once hauled from mines in heavy wagons famously pulled by 20-mule teams. The aerospace museum is located next to the Twenty Mule Team Museum.) The museum, which opened 14 years ago, could have become one of those sleepy repositories of moribund airplanes and memorabilia located in overlooked towns and ramshackle airfields across the country. That may be its ultimate fate, but for a period of time, the museum appeared to have the energy to draw visitors in—and not just the now-quiescent energy of the early U.S. nuclear and space programs. It had the considerable energy and gravitational pull of Waldo Stakes.

Stakes, 62, is a quixotic, self-taught, one-of-a-kind aerospace maven and aviation geek who saw an opportunity in Boron, a northeastern neighbor of Edwards Air Force Base and so a witness to some of the defining feats of U.S. aerospace history. The town’s unofficial motto, “Where the Wild West meets the cosmos,” reflects the mythic characters of the early U.S. space program: test pilots and astronauts who replaced the cowboys as American heroes, riding rockets instead of horses. As Stakes once said to a father and his two young sons who’d wandered in after spotting the airplanes out front, “This museum isn’t just about pilots and flight test. It’s about people with guts like you wouldn’t believe. I like to call it the ‘Right Stuff Museum.’ ”

Between 2010 and 2015, Stakes expanded the museum’s exhibits. He hauled in exotic artifacts that he’d accumulated over the years: an LR-101 used as a vernier thruster on an Atlas; his own missile-like ice racer, powered by an XLR11 thrust chamber developed for the Bell X-1; the mangled remains of the rocket-powered, record-setting speedboat Lee Taylor was piloting at about 300 mph when he crashed fatally on Lake Tahoe in 1980. He also helped settle the case of the rocket motors that had so energized the FBI, Air Force, and Department of Homeland Security. Although engineering marvels, the engines are potentially lethal technology. Stakes recalls the day the agents paid a visit: “They said, ‘We’re going take these engines and scrap them because they’re a national asset.’ ” Instead, Stakes persuaded the agents to lend them to the museum for five to 10 years.

The LR-89s stayed, and so did Stakes, signing on as the museum’s curator.

The museum was named after the late Vernon P. Saxon Jr., a Boron-based test pilot who had served as the vice commander of the Air Force Flight Test Center at Edwards in the 1990s. Artifacts from Saxon’s career served as the core of the collection, and a McDonnell F-4D Phantom II, one of the types that Saxon flew, sat outside, glowering at passersby on the town’s main drag.

Stakes himself has amassed an impressive collection of military-surplus rocket motors and other Space Age components that he’s repurposing for an assault on the land-speed record. Land-speed racing is a sport that marries exacting engineering to preposterous risk, so it attracts a curious breed of highly motivated fanatics who occupy the borderland between genius and insanity. And hearing Stakes talk a mile a minute about everything from gyroscopic precess moments to UFO propulsion systems, a listener is tempted to dismiss him as one who has crossed over.

But he’s helped design cars and motorcycles that have broken dozens of speed records, and he’s almost finished building a streamlined racer—with a theoretical top speed exceeding 1,000 mph—fabricated around 1960s-era components from the X-15, Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo programs, not to mention the Corporal, Sergeant, and Honest John ICBMs. “I’ve got $8 million of engineering in my car, the greatest hardware ever made,” he says.

One day he got a call from Al Peterson, president and CEO of the National Test Pilot School in Mojave. Peterson was looking for a retirement home for the school’s rare two-seat Saab 35 Draken that had once been flown by the Danish air force. The fighter had to be disassembled and demilitarized before being moved to Boron. Rather than rent a crane to help reassemble it, Boron honorary Mayor Dale Slavinski enlisted the local high school football team to hold the wings up while Stakes and Randy Ciapponi, then museum co-director, bolted them to the fuselage.

The museum scored its biggest coup when Stakes secured virtually the entire holdings of the recently shuttered Milestones of Flight Air Museum in nearby Lancaster. The haul included three airplanes: a sleek little Reno racer seemingly shrink-wrapped around a twin-turbo big-block Chevy V-8, a plucky 1929 Pietenpol homebuilt powered by a hot-rodded Ford Model A engine, and a Kitfox built by junior high school students. The museum didn’t have enough time or money to get permits to flatbed the airplanes to Boron, so Stakes, who believes in asking forgiveness rather than permission, lined up volunteers to transport the airplanes on pickups and open trailers along the little-traveled roads on the back side of Edwards.

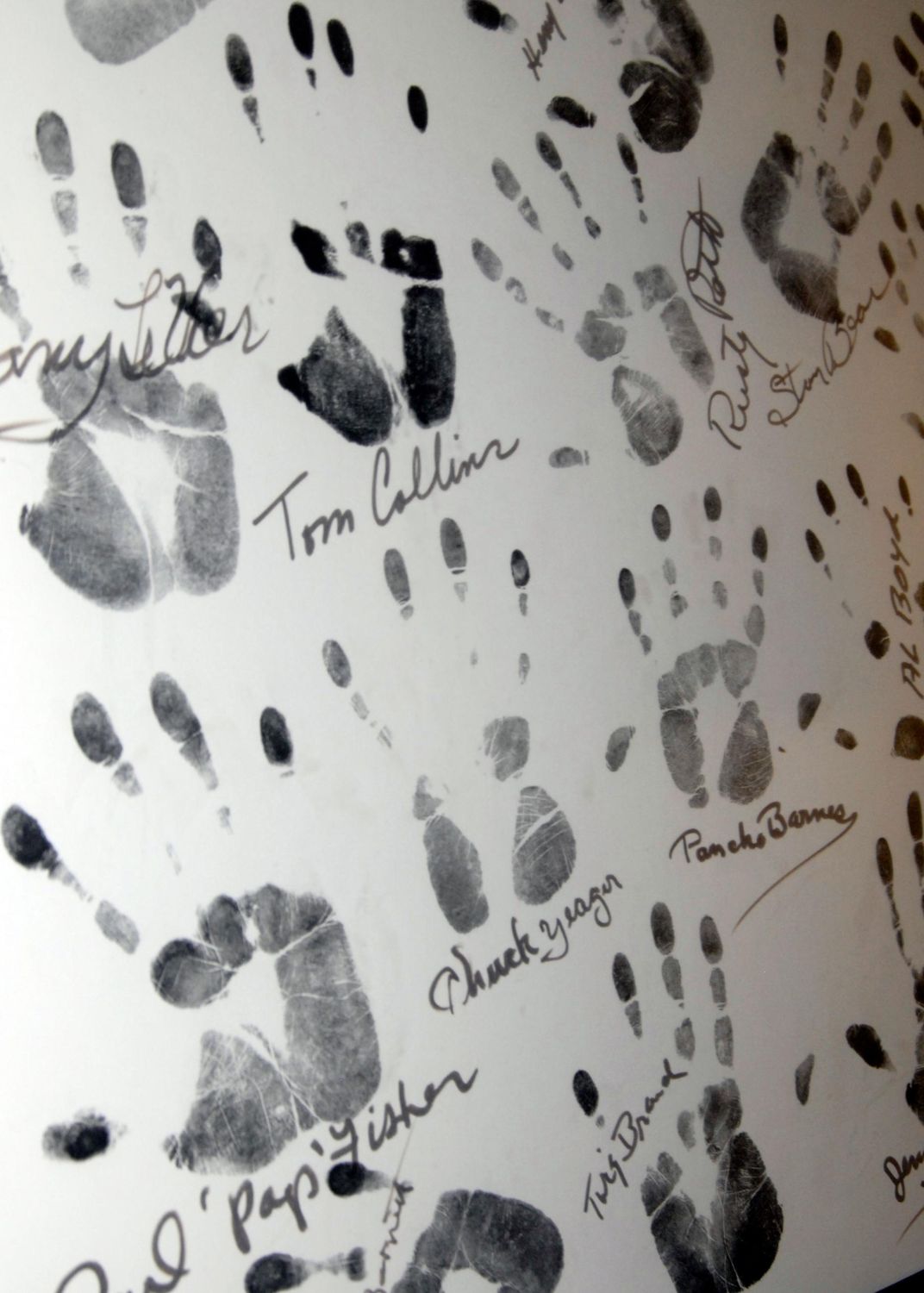

Five airplanes are now displayed outside the museum, along with several rocket motors, a jet turbine, an R-2800 radial from a Corsair that raced at Reno in 1968, and a rock that local miners provided to the Jet Propulsion Laboratory to help engineers figure out how to drill on the moon. Inside, highlights include a P-38 instrument panel, a B-17 bomb sight, the de-mating controller for the 747 that carried the space shuttle, the wood skis from a Ford Tri-motor that Admiral Richard Byrd used on one of his South Pole expeditions, and the LR-8 rocket motor that may—or, more likely, may not—have pushed the X-1 through the sound barrier for the first time.

But the artifact that would truly have put Boron on the map of Edwards lore is the one that Stakes started chasing in 2015, a possession of the late Boron resident Pancho Barnes. Aviation’s bad girl, the pioneering pilot owned the Happy Bottom Riding Club, a favorite haunt of flight test giants like Yeager. Barnes died in 1975 in a house two blocks from the museum. Stakes had heard that an 80- by 100-foot wood hangar she’d commissioned was at El Mirage Field, 45 miles west of town, and he became fixated on acquiring it for the museum and bringing it to Boron.

Built in 1939, the structure had been a landmark at Barnes’ club. Technically known as Rancho Oro Verde, the club was gutted by a fire in 1953, and the surviving structures were sold and moved. Once used as a base for glider operations, the hangar became a warehouse at the General Atomics Aeronautical Systems drone facility, and the company was planning to have it demolished—if the elements didn’t destroy it first. “It’s a miracle it’s still standing,” says Dick McRae, the company’s director of facilities and administration. “It’s been waiting for Waldo to arrive.”

Stakes estimates that it would cost $200,000 just to move the hangar, and another $1.42 million to bring it up to current building code and retrofit it with offices—a seemingly unfathomable stretch for a museum that struggled to raise $7,000 to disassemble, de-mil, and transport the Draken. “People ask me where the money is going to come from. I have no idea,” Stakes admits cheerfully. “But if you’re driving from New York to Chicago at night, all you need to do is see that first 150, 200 feet. Eventually, you’ll make it all the way to Chicago.”

Alas, Stakes’ boundless optimism butted heads with the ugly realities of institutional politics. Some of his critics—and Stakes, it should be said, can be a polarizing figure—felt that he’d strayed too far from the museum’s original focus on Saxon and military aviation. Last year, the museum leadership moved in a different direction. Then there was a counter-revolution, and Stakes was reconfirmed as curator.

Still, feelings were hurt. Saxon’s memorabilia were removed. The episode spooked Stakes, and he also pulled the artifacts he’d lent to the museum for fear that he might lose control of them. Today renamed the Boron Aerospace Museum and still operating under the auspices of the Boron Chamber of Commerce—“where it rightfully belongs,” says Stakes; “they are wonderful people”—it is focused primarily on military aviation. Director Tammy Brown, a local business owner, says the museum is open for visitors 10 a.m. to 4 p.m., Wednesday through Sunday.

Meanwhile the hangar from the Happy Bottom Riding Club is still standing at the General Atomics facility and still available. If an aspiring museum can find the funding to move it, Stakes says, he’d be happy to help. “If you don’t dream big,” Pancho Barnes once said, “only small things happen.”

Stakes has a new big dream. He recently took out a loan against his house to open a museum celebrating what might be called, for lack of a better word, daredevilry—not just in rocketry and aviation, but also various types of death-defying record attempts. “You’ve got to have a little P.T. Barnum to get people to come to a museum that’s 100 miles from nowhere,” he says. He plans to put four shipping containers of artifacts on a parking lot in Baker, California, a broiling hot desert town best known as a pit stop on the drive between Los Angeles and Las Vegas. “I’m trying to save every nickel so I can spend it on inspiring people,” he says. “Plus, the containers would make the museum portable in case the shit hits the fan.”

Stakes may be a dreamer, but he ain’t stupid.