Will Drones Be the Next Police Cars?

Law enforcement prepares for its newest rookies.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e5/cc/e5ccf376-8f01-4ef8-b330-b821a000d6d1/03-cops-robots-mainimage.jpg)

The grainy black-and-white video is reminiscent of the famous images of U.S. “surgical strikes” during the first Gulf War, but without the crosshairs. It’s an infrared image, overlaid with white numbers representing the aircraft’s shifting position and remaining battery life.

A white blob ambles across a field, something about its movements immediately familiar. Ben Miller points to his computer screen. “There’s a human,” he says. “I can’t tell you who they are; I couldn’t even tell you if they’re a girl or a boy.”

He does this a lot: explaining why his drones would have difficulty, and little reason for, invading anyone’s privacy. There’s more to that issue, but in rural Mesa County, where this technology is mostly used to search for missing people and photograph crime scenes, it seems like background noise.

Miller is the quartermaster—a kind of gear-monger—at the Mesa County Sheriff’s Office in Grand Junction, Colorado. His duties include buying evidence management software and supplying officers with batteries for their hand-held radios, but he’s also responsible for the department’s unmanned aerial vehicle program. Miller is a born tech geek; he has that combination of intelligence and enthusiasm that drives him to adapt the latest cool tool to his line of work.

One of Miller’s three UAVs recorded these video images on a search-and-rescue mission, and although the aircraft didn’t spot the missing woman (other searchers eventually did), it did cover much more area than the officers on the ground.

But there are obstacles to the use of search-and-rescue drones. Miller picks up a framed cover from a February 2013 issue of Time magazine—a photo-illustration of a military Predator drone buzzing a suburban house. “This is a frustration of mine,” he says. “That’s not even a real photo.”

It’s this kind of representation that spurs citizens of Mesa County to contact the sheriff’s office with all kinds of concerns about its UAV program—from vague discomfort with aerial robots to all-out conspiracy theories. But Miller, along with his UAV team and Sheriff Stan Hilkey, believe that the key to making UAV deployment possible is winning the community’s hearts and minds, so they keep an open door. One couple came in concerned about the giant, ominous drones they thought the sheriff’s office would be flying out of Grand Junction’s airport. When the sheriff held out his arms to demonstrate the size of the aircraft in question, they said, “Oh.” Miller brought a three-foot Draganflyer UAV with him when he testified at a Senate Judiciary Committee hearing in March 2013 to deflate similar fears.

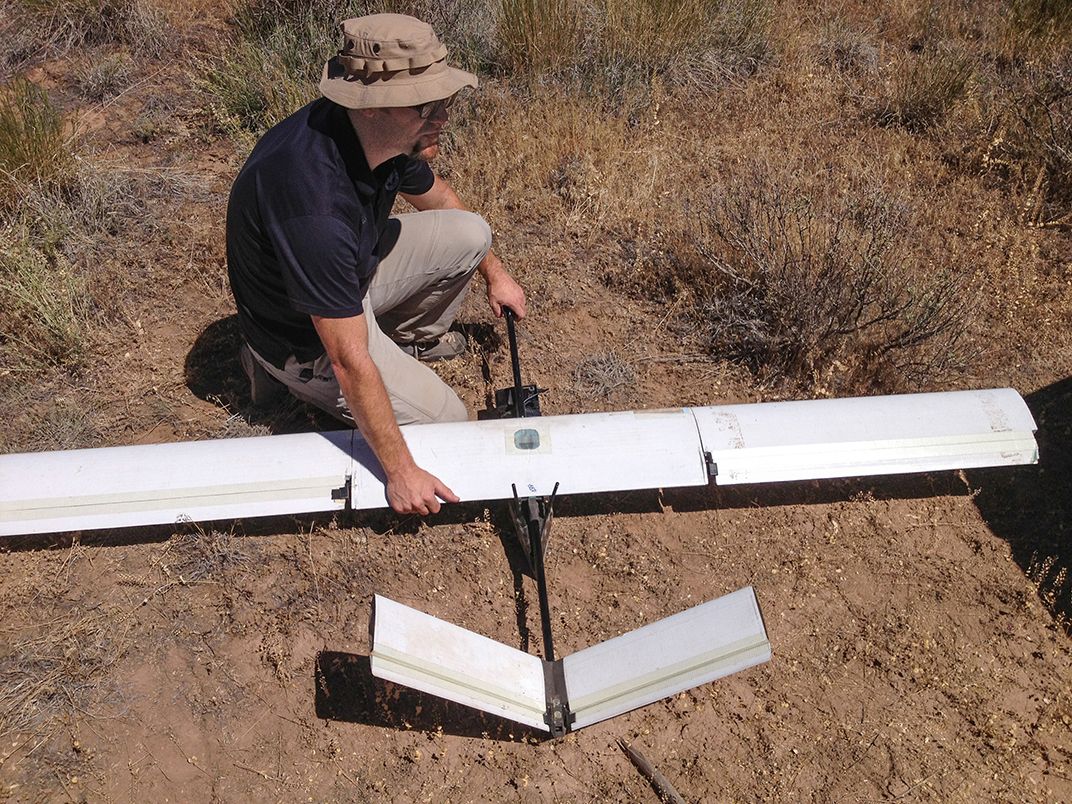

Just outside Grand Junction, on a bluff above Interstate 70, Miller pulls a three-foot-long black case out of an SUV. In it are sections of aluminum-alloy pipe, some white panels, a handful of electronics—seven pieces in all. Miller starts snapping them together. A group of government employees from the U.S. Geological Survey, the Bureau of Land Management, the Colorado Geological Survey, and the Colorado Department of Transportation watch, interested in how unmanned aircraft can help them do more for less.

It takes Miller only a few minutes to assemble the Falcon, a four-foot-long, 9.5-pound, battery-powered, fixed-wing airplane. It carries a high-resolution infrared digital camera, flies autonomously with only a series of GPS waypoints to guide it, and lands by deploying a parachute and drifting nose-first to the ground.

This Falcon belongs to Chris Miser, the airplane’s designer and the owner of the Aurora, Colorado company that makes it. Miser is back from flying the Falcon in South Africa, testing whether it could be used to monitor poaching on wildlife reserves. His company has worked closely with Miller for the past two years, setting up the sheriff’s department’s two Falcon systems and flying missions with them as one of their official pilots.

Miser and Miller conduct a quick pre-flight check, wiggling the Falcon’s aileron servos and testing its front-mounted propeller motor. Miser notices the onboard video camera—which feeds a first-person perspective from the aircraft to his laptop—isn’t working. He decides to fly anyway. “It’s nice to have,” he says, “but you don’t need it.”

The sheriff’s office is lending its UAV capability to the U.S. Geological Survey, which wants to assess a landslide that spilled onto I-70. The USGS needs aerial photos, taken at six-month intervals, to see if the landslide is still moving toward the interstate. It would cost hundreds of dollars per hour to hire a manned aircraft to take the photos, but Miller estimates that this mission will cost the county taxpayers just $20.

Miser loops a 20-foot bungee cord around a scraggly bush and attaches the other end to the fuselage of the Falcon, walking the airplane backward until the bungee is taut. When he lets go, the bungee slingshots the Falcon into the air. An accelerometer cribbed from smart-phone technology tells the Falcon it’s airborne, and the propeller starts spinning automatically. The airplane immediately ascends to the designated 250-foot altitude, reaches its first waypoint over the landslide, and begins to methodically pace back and forth across the sky, taking pictures.

Miser sits in his SUV watching the Falcon’s progress on his laptop. Although he can’t see what the Falcon sees, he follows its progress on a Google Earth satellite image of the area that is covered in dots connected by white lines—the aircraft’s flight plan. A comm box on the dashboard transmits the navigational data to the Falcon, while the onboard avionics provide “stability-augmented control” to keep the aircraft level and steady, even in rough air.

Miller’s eyes are glued to the airplane. This two-person protocol is the safest way to fly UAVs; it ensures the operators never lose “situational awareness.” Without the onboard video link, it’s especially important.

Of the roughly 18,000 law enforcement agencies in the United States, only a few hundred can afford helicopters or another type of manned air support. Even for those agencies that have aircraft, the operating cost is painful—on average, $650 per hour.

The range of potential law enforcement applications for small UAVs is limited in most cases by the kind of drone that police departments can afford—usually something in the Falcon range, about $55,000 for a pair. Such small aircraft can carry only so much weight, so their batteries are small, which limits flight duration (an hour for the Falcon). Miller points out that while these UAVs are well suited for search-and-rescue and aerial photography, they’re not so helpful for, say, surveillance of drug dealers, because the UAV will eventually have to go home to recharge.

Mesa County’s other UAV, the multicopter Draganflyer X6, is an example of the right tool for the job. Though it can stay aloft for only 15 minutes, it’s useful for crime scene photography. The high vantage point allows for identification and analysis of crime scenes, such as when Miller created a composite of aerial photographs showing a grassy median that had been shredded by a joyriding teenager. Photos taken on the ground wouldn’t have shown how extensive the damage was.

Public agencies like the Mesa County Sheriff’s Department are allowed to fly once they’ve acquired a certificate of authorization (COA) from the Federal Aviation Administration. The FAA says that as of last January, 545 such certificates were active. Flying at night is not allowed, nor is flying more than 400 feet above the ground, within five miles of an airport, or out of the operators’ line of sight.

Some 36 law enforcement agencies nationwide are operating UAV programs under COAs, which are generally good for two years. Of those agencies, only a handful have flown their drones outside of training. Captain Leonard Montgomery of the North Little Rock Police Department in Arkansas had a run of bad luck with his Rotomotion SR30 helicopter, acquired in 2008 when only a few police departments in the country were trying out unmanned aircraft. The gas-powered SR30 is complex and difficult to maintain, and Montgomery and his team had constant trouble with it.

“We were at the cutting edge—actually the bleeding edge,” says Montgomery. “We had to learn as we went along. Basically, we picked the wrong platform.” The five-foot-long, 15-pound helicopter was totalled in a crash last November, and Montgomery hasn’t replaced it.

In 2012, Congress passed legislation that requires the FAA to simplify the COA process for public agencies in the near-term, and to allow broad public and commercial use of unmanned aircraft by 2015. (Last February, the Transportation department’s inspector general told a Congressional panel that the agency would not meet the 2015 deadline.) The current 18-page COA application is preceded by a questionnaire that strays from the certificate’s actual requirements—for example, by asking whether any of the potential operators has a pilot’s license (which is not required to operate a UAV). The FAA also requires that even a minor software update be cleared through the COA office, and that the operating agency designate every possible emergency landing site in its jurisdictional area (in Mesa County’s case, about 3,300 square miles).

A new set of rules about small UAVs (under 55 pounds) is due out this year, and the FAA is working with the Department of Justice on a new course to certify public safety UAV pilots specifically. But overall, the agency has been slow in taking steps to meet the growing need for drone regulation. According to Miller, the delay could be costly.

“This process that the FAA wants to be a risk-mitigating process creates more risk, in the sense that there’s no regulation,” he says. If rules are too slow to come out, he adds, public agencies—and private citizens—will fly anyway. “The FAA is driving users into a non-compliant culture.”

Miller suspects the agency is buying time, trying to hold back the wave of unmanned fliers while officials gather their thoughts about the mammoth task of integrating what could be tens of thousands of tiny aircraft into the national airspace system. But that other sticky issue, privacy, may also be causing delays.

More than a few Americans and their representatives in Washington have begun to ask what unmanned aircraft are capable of, and in particular whether they could violate Constitutional protections against unreasonable searches. In terms of government use of UAV technology, that concern is aimed squarely at law enforcement.

“This isn’t even necessarily about unmanned aircraft—this is also about trust,” says Ben Gielow of the Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems International, an advocacy and lobbying group. “I think the public would be okay if an unmanned aircraft was in a fire truck, but when you put it in a police car, then people get a little bit more worried.”

All but seven states have passed or are considering legislation that addresses the use of UAVs, from limiting who can use the aircraft for surveillance to outlawing weaponized drones, and much of the legislation is designed to curb privacy abuses by law enforcement agencies. While Colorado has yet to propose any such laws, Miller says he would rather see more stringent protection of privacy itself, rather than laws that stigmatize UAV technology.

“The Constitution does not care what kind of tool you use,” he says. He points out that police need a warrant to gather information in areas where people have a “reasonable expectation of privacy,” such as an enclosed back yard, even if the surveillance method is an unmanned aircraft. While the widespread use of UAVs can help drive the discussion of how to protect privacy, he says, the technology isn’t inherently invasive.

The American Civil Liberties Union, however, published an article last year arguing that drones are different from other surveillance tools. They’re fairly cheap, which means law enforcement can acquire them relatively easily. They’re also small and quiet—people being watched by a 900-horsepower manned helicopter know it, but the tiny Draganflyer is another story. The ACLU is recommending tight restrictions on how drones and the information they collect can be used.

The FAA is working on integrating UAVs “as quickly as [it] can,” says spokesman Les Dorr, adding that the need to address privacy concerns and promote economic growth is part of what’s slowing the agency down.

Back at the landslide, the Falcon’s flight plan is veering a little too close to bluffs topped by sheer rock cliffs. Miser asks Miller to take control of the aircraft and hands him a PlayStation 2 controller with masking tape labeling the different inputs. Miller flies the Falcon in a holding pattern while Miser drags the waypoints on his computer screen to a safer distance. Then he switches the Falcon back to autopilot mode while Miller keeps his eyes on it. The airplane is aimed at one of the cliffs, but Miser seems to think he’s rearranged the waypoints properly.

“You need to turn left,” Miller says. He thinks Miser should pick up the controller and divert the Falcon. His tone is perhaps a bit too relaxed. “Turn left.”

A second later the Falcon crosses in front of the cliff edge. Everyone knows what’s about to happen, but no one says anything. At its cruising speed, 30 mph, the Falcon slams nose-first into the cliff. The wings collapse, and as the remains of the airplane crumple to the foot of the rock wall, the bright orange parachute spurts out and half-opens.

The crash is anticlimactic—no fireball or thunderous noise. It looks about the way you’d expect, more or less like a toy airplane hitting a wall.

Miser scrambles up the slope to the wreckage. While it has come apart, most of the airplane is undamaged. The bracket that joins the wings to the fuselage is broken, as is some of the circuitry in the drone’s brain, but the wings are fine and the propeller is intact. The rounded metal spinner at the nose shows only a small dent.

Miser says repairs will take about a day and cost maybe $400. Eager to point out the soundness of his product, he takes full responsibility. “The airplane did exactly what it was supposed to do,” he huffs. “That was pure user error.”

He should have trusted his spotter more, he says, though he points out that Miller could have been a little more assertive with his advice. In theory, though, the spotter system works—and had the onboard video feed been working, Miser himself would have seen the cliff coming. Most importantly, Miller says, had they been flying on police business, especially had the Falcon been near anyone who could get hurt, a crash never would have happened. Without everything in working order, they simply wouldn’t have flown, or they would have flown a backup aircraft. Miser knew the consequences when he took the risk, and, ever the engineer, he chalks the crash up to a learning experience. “That’s why you don’t fly without video,” he advises no one in particular.

“The whole concept of a crash in aviation as we know it is there is usually loss of life or significant injury, and it’s very expensive,” says Miller. A failure with unmanned aircraft of this size, he says, is simply not a big deal. “If the FAA can’t accept that, it’ll be a hindrance—not just to law enforcement, but to everybody.”

Not that a small UAV couldn’t do damage; Miller acknowledges that you don’t want a Falcon crashing through your car windshield. But preventing an airplane crash is up to pilots, whether they’re in the cockpit or not.

While building Mesa County’s drone capabilities is a challenge in itself, Miller acknowledges that he has a larger role to play in the unfolding drama of domestic drone use. Besides testifying last year before the Senate Judiciary Committee, he serves on a multinational panel on UAV operating standards. For the past two years, he’s flown UAVs for 225 hours and has been interviewed by reporters nationwide. It’s a sensitive stage, where one misstep could brand UAVs a liability rather than an asset, and Miller is determined to do things right.

“You make a mistake following the rules, okay,” he says, with a nod to the Falcon cliff crash. “You make a mistake not following the rules, it’s bad for everybody.”

The tricky part, at this point, is knowing what the rules are.