You’ve Got (Balloon) Mail

In September 1870, not long after the start of the Franco-Prussian War, the city of Paris was under siege by Prussian soldiers. By the 19th, the German army had blocked all communication into or out of the city. There was nothing worse, wrote French journalist Francisque Sarcey, than to “live cut o…

In September 1870, not long after the start of the Franco-Prussian War, the city of Paris was under siege by Prussian soldiers. By the 19th, the German army had blocked all communication into or out of the city. There was nothing worse, wrote French journalist Francisque Sarcey, than to "live cut off from the universe in the capital of the civilized world, like Robinson on his island."

Rumors swept through the city. Some said the Prussian army was about to be crushed by a million-ton sledge hammer carried aloft by a fleet of balloons. Others reported seeing French and Prussian aeronauts battle in the air.

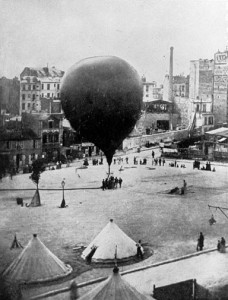

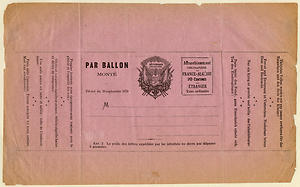

What was true was that the director general of the Posts immediately established a "Balloon Post" to carry messages outside the city. For Parisians, "The success of this aerial trip," wrote Wilfrid de Fonvielle, "produced a feeling of happiness as if the enemy had been vanquished in a great battle."

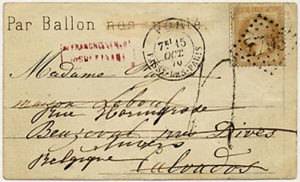

Some 67 balloons ascended from Paris during the 128-day siege, carrying more than 24,000 pounds of mail. (The National Postal Museum has an extensive collection of these letters. In an attempt to send messages into Paris, letters were placed inside zinc balls, which were tossed into the Seine and were supposed to float downriver until captured by a net; while none were recovered by Parisian residents during the siege, the balls continued to turn up as late as 1982.)

There weren't enough balloons for the task, so Parisians immediately set up two balloon-making factories. Silk was difficult to find, so calico was used for the envelopes, yards of it varnished by women seated at long tables. Sailors made the dragging ropes, netting and baskets; each balloon took 12 days to make. Pilots were recruited from naval detachments in the city and from the civilian population. By October 12, two of the new balloons—the Washington and the Louis Blanc—were ready. The Washington came under fire, eventually smashing into some trees. The Louis Blanc traveled for three hours and finally made it to Belgium.

Two aeronauts were lost at sea. Six were captured by Germans. One drifted more than 800 miles to Norway. But these novice pilots transported at least 110 passengers, some 400 pigeons (letters were sent into Paris using an early form of microfilm; once the pigeons carrying their fragile film reached Paris, a group of clerks copied each message and sent it to the addressee), three million letters—and hope. John Fisher writes in his 1965 book Airlift 1870, "As the siege went on, as ascent followed ascent, the balloons, in the eyes of Parisians and in the eyes of the world, came to be regarded not merely as useful carriers but as symbols of French daring and enterprise and success. Each flight accomplished, each letter delivered, was in a sense another little victory over the great German war-machine; a defiance, a gesture made by an individual."