Up-Close and Personal With Chicago’s Most Infamous Criminals

“Gangsters & Grifters,” a book by the Chicago Tribune, recalls a time when photographers had unprecedented access to the world of crime

The photography archive of the Chicago Tribune lives five stories underground, beneath the Tribune Tower on Chicago's Michigan Avenue. Many of the photo negatives stored there have, for all intents and purposes, been forgotten to history—printed once, maybe a century ago, and then filed away in envelopes sometimes labeled in pencil with a date and subject, or sometimes not labeled at all. The negatives, 4x5 glass plates or acetate negatives, come from a speed graphic camera—the world's first press camera, forever immortalized in film and popular culture by its slightly-cumbersome box shape and large flash bulb. But for all its drawbacks—weight, size, balance—the speed graphic camera was the first to allow photographers the mobility needed to capture scenes in the field, as they unfolded. For photographers working in Chicago through the early and mid-20th century, there was perhaps no beat more intriguing than the city's bustling criminal underbelly.

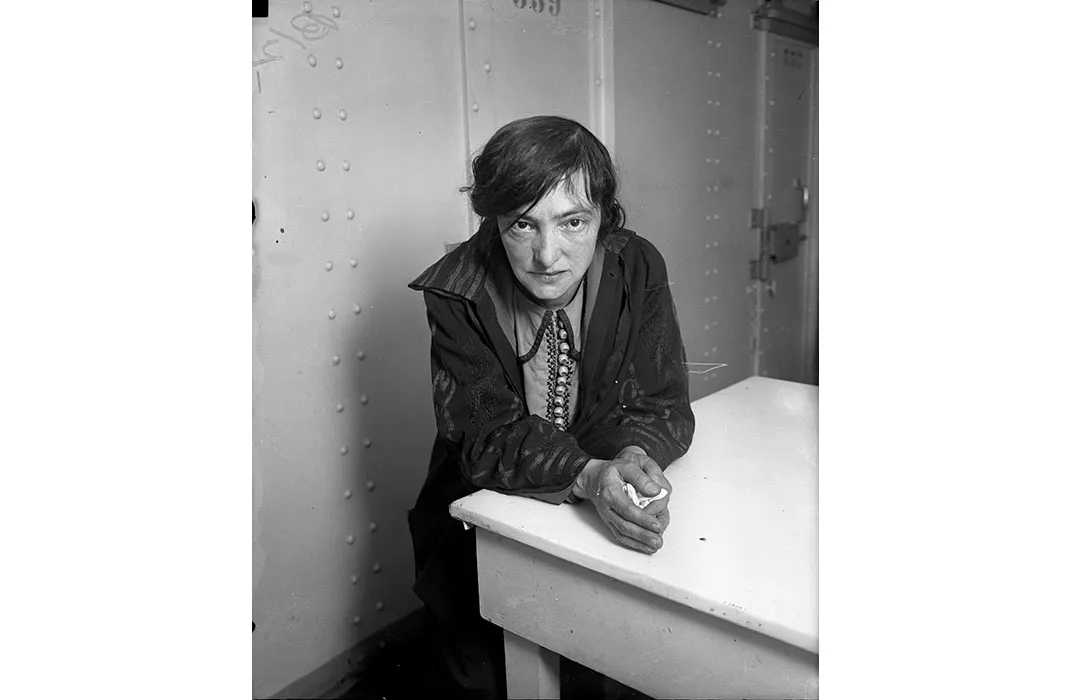

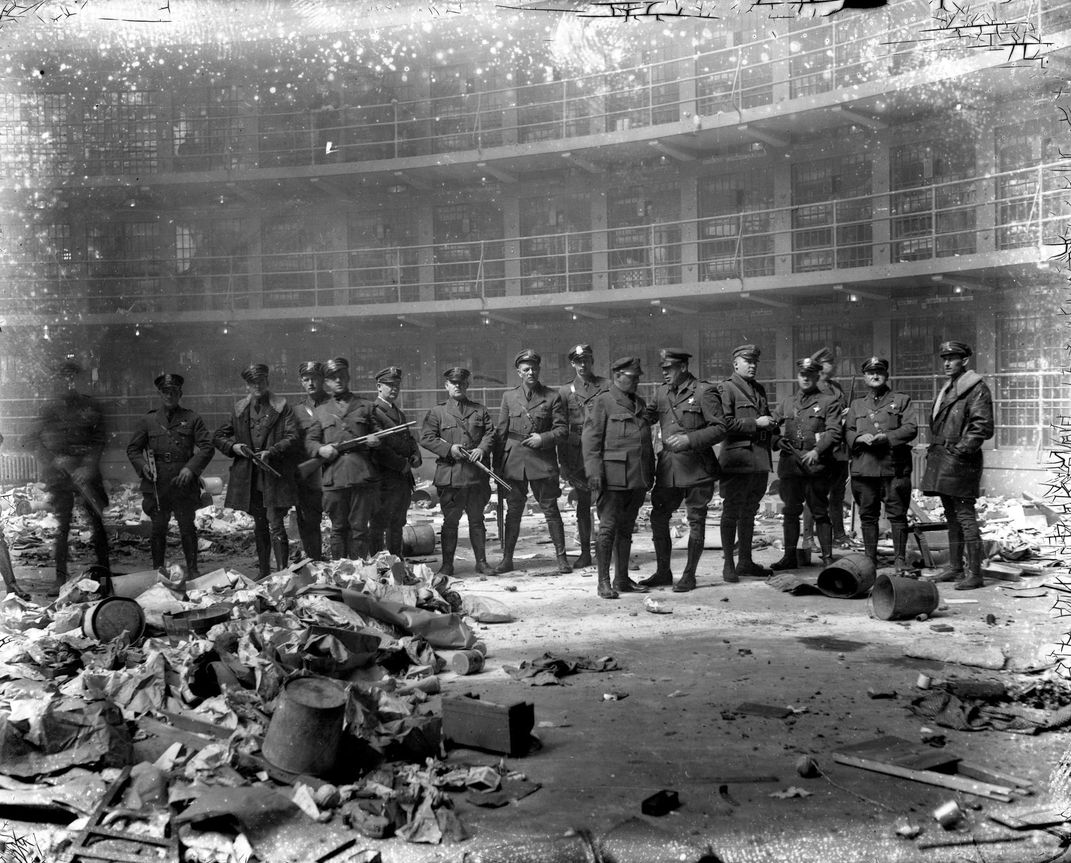

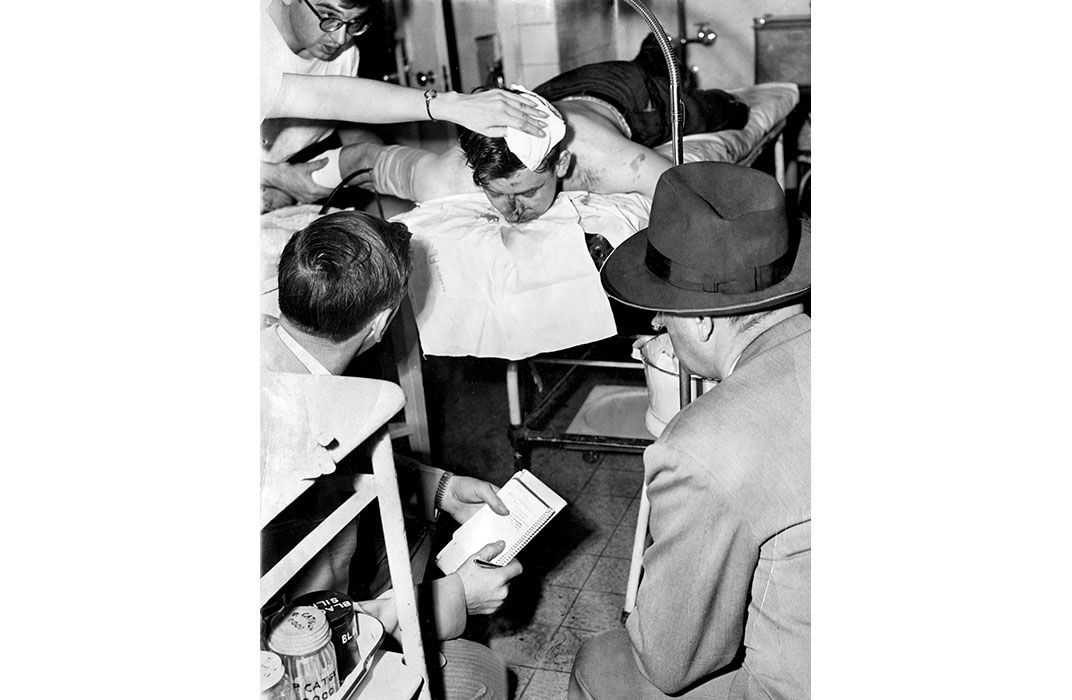

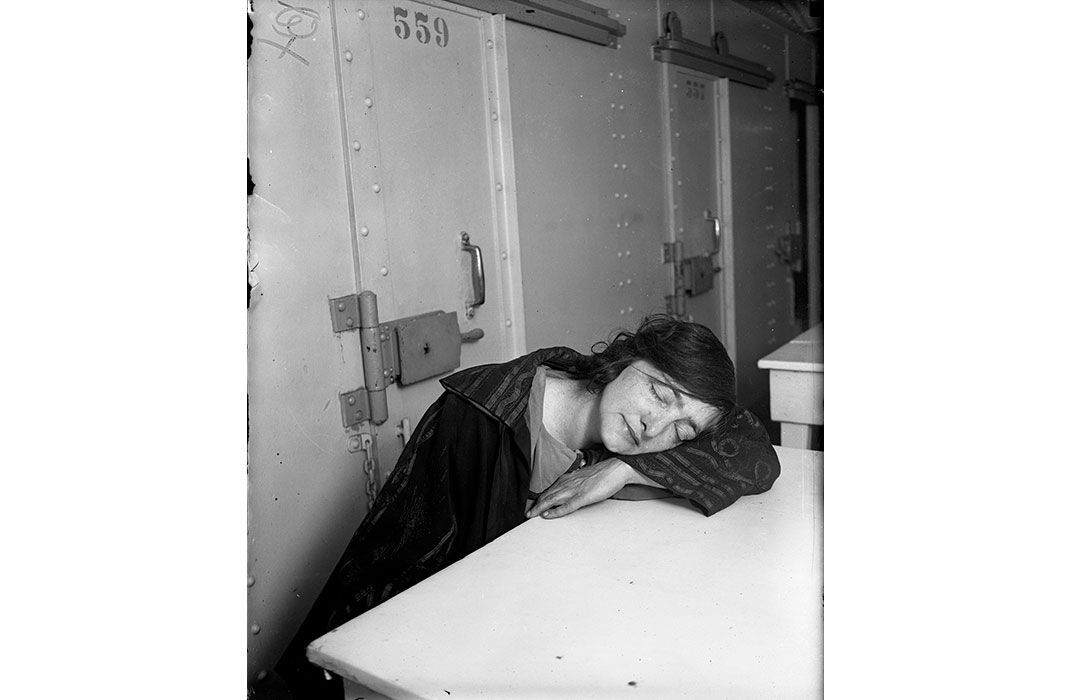

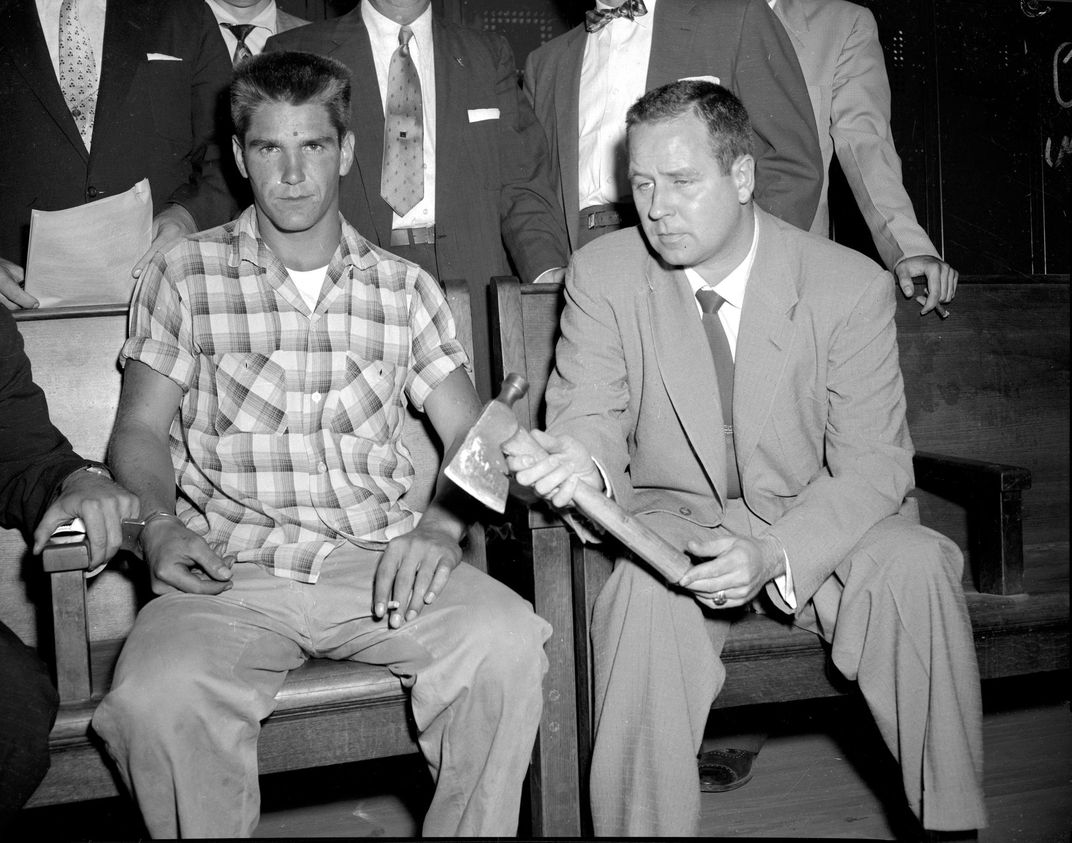

When Tribune photo editors Erin Mystkowski, Marianne Mather and Robin Daughtridge set out to catalog the archive's vast expanse of 4x5 negatives, they weren't necessarily looking for just crime photos. First, they simply wanted to get through the archive—cataloging 60,000 of the more than 300,000 negatives kept in storage—in order to merely get an idea of what was there. What was there, it turned out, was a lot of vintage crime photographs—some of which had never been seen outside of the walls of the Tribune. Together, the editors researched the photographs origins alongside the stories that they told—who was Moonshine Mary? Who were the "hoodlum" or "holdup man" mentioned in the caption? After careful vetting, they compiled a collection of vintage crime photos, ranging in date from the early 1900s to the 1950s, into the book Gangsters and Grifters: Classic Crime Photos from the Chicago Tribune. The book is a remarkable testament to a bygone era of photojournalism—one when photographers enjoyed unbarred access to crime scenes and courtrooms. As such, the photographs stun in their intimacy with the grotesque—some of the book's most profound photos are close-up shots of corpses, slumped behind the wheel of a car or strewn on the ground after an outburst of mob violence. The photos depict the other side of the process as well—policemen examining evidence, searching underwater for a murder weapon or testing the new technology of a bulletproof shield by unloading a pistol at the shield's inventor.

"The access in these photos is really astounding and so far different from what we’re used to today. The evolution of ethics—both on the part of the police force and journalists—has evolved so much," Mystkowski says. "In the book, you'll see photos of officers holding up a sheet so they can show the body at the crime scene. That's a kind of photo that we would never be allowed to take, and if a photo like that were taken now, we would never run it. Back then, there was a different attitude of what journalism meant—what it meant to tell a story."

Such free access wasn't the particular luxury of photojournalists, however—everyone had amazing access to crime scenes and even corpses. One particularly fascinating photograph in the book shows the body of John Dillinger, Public Enemy Number One at the time of his death in 1934, outstretched at the Cook County Morgue. Behind a glass barrier stand two women—in bathing suits—leaning against the glass, mere inches from Dillinger's rigid body. "That particular photo has a very interesting background story," says Mather. "It was taken at the Cook County Morgue, and they actually had a big problem—the police officers weren't policing the body, so people were walking in and touching his body and even making death masks of his face with no authorization. There were hundreds of people lined up outside of the morgue to see the body of Public Enemy Number One...I think it's so interesting that there wasn't any quarantining or setting up police tape at that time."

But Mather and Mystkowski's favorite photograph is neither of a corpse nor of a crime scene—it's of a young beer runner named Al Brown being led into court. "It's not one of the best particular photos, but it's the process of how we found it that made it really exceptional to me," Mather says. "We had done a lot of crime research, and we were looking up things for Prohibition, and this [particular photo] was labeled 'Beer runner, Al Brown.' It looked kind of boring when we held it up to the light, before we scanned it in, but I thought that I would just scan it in anyway, to see what it looked like. When it came to life on the computer screen, we realized 'This is Al Capone.' Because we weren't looking for it, we didn’t realize what we had."

When asked if in modern day photojournalism—with its stringent ethics and focus on privacy—photography has lost anything, both Mather and Mystkowski pause. "We love these photos because of the access that we don’t have now: the courtroom scenes of the wailing wives as their husbands are getting sentenced to death, we don’t see that same emotion these days—or we see it in different ways," says Mather. Mystkowski agrees. "Part of what makes these photographs so fascinating is that they are a glimpse into these really harsh moments in someone's life. It can be the crime scene, which is gory and difficult to look at, or it can be an emotional reaction to it, but it does have this immediacy that is sometimes hard to achieve nowadays, for better or for worse."

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/natasha-geiling-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/31/10/3110ecab-b510-4d9c-ab87-23c5b3c3f569/crime_042.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/natasha-geiling-240.jpg)