10 Vintage Menus That Are a Feast for the Eyes, If Not the Stomach

From the late-19th century to the 1970s, restaurants had one surefire way of standing out

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20130226082055McDonnells_thumb.jpg)

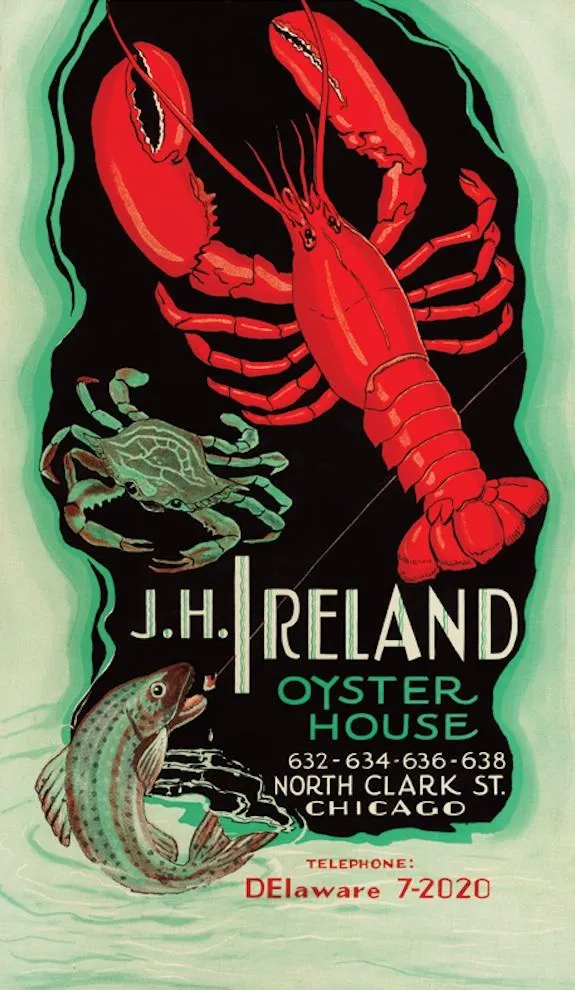

The Chicago seafood restaurant J. H. Ireland Grill opened in 1906 and had a colorful client list. It attracted everyone from gangster John Dillinger (who preferred the grill’s frog legs) to lawyer Clarence Darrow, who went there to celebrate big wins. But the co-founders of Cool Culinaria, which finds and sells prints of vintage menus, remember it for a different reason: its menu design. As colorful as its past, the best-selling menu uses bright colors to convey the fresh and vibrant ingredients to be found inside.

Menus from across the country featured fantastical fare with an artistry that often goes unrecognized, according to Cool Culinaria co-founder Eugen Beer. Along with Charles Baum and Barbara McMahon, Beer works with both private collectors and public institutions including universities and libraries to license menus from the late 19th century through the 1970s. Beer is British, and McMahon Scottish, but he says, “America, for whatever reason, has this vast collection of fantastic art that sits in boxes.”

Their favorites are from a golden age of design and dining ranging from the 1930s to the 1960s.

“You had this incredible explosion of restaurants in the ’30s, ’40s and ’50s when the American economy, partly driven by the Second World War, was doing incredibly well. And you had the great highways,” explains Beer. “In Europe at the time, of course, we didn’t have that. I grew up in the United Kingdom in the era of post-rationing and even in the ’50s in England we still had rationing.” But, he says, “In America, you had a fantastic boom in independent restaurants and you had these buccaneering restauranteurs who, in order to give their establishments a sense of identity, invested money in the design of their menus and actually employed well-known artists or interesting designers to produce them.”

Beer firmly believes that the menus they deal with are museum-worthy works of art and will even call in art restorers to handle some of the more delicate cleanup jobs.

But reading the insides can be just as much fun as looking at the artful covers. “I always stop dead at my desk to read the interiors almost like a book and to imagine myself sitting in that diner in the 1940s or a sophisticated nightclub after Prohibition in the 1930s,” says McMahon. Sometimes diners left clues to help McMahon complete the picture: “There was one that I really love, it says in this spidery handwriting, Johnny and I dined here, 1949.”

“They’ve even circled on the actual menu what they ate,” adds Beer.

“Hamburgers, wasn’t it?”

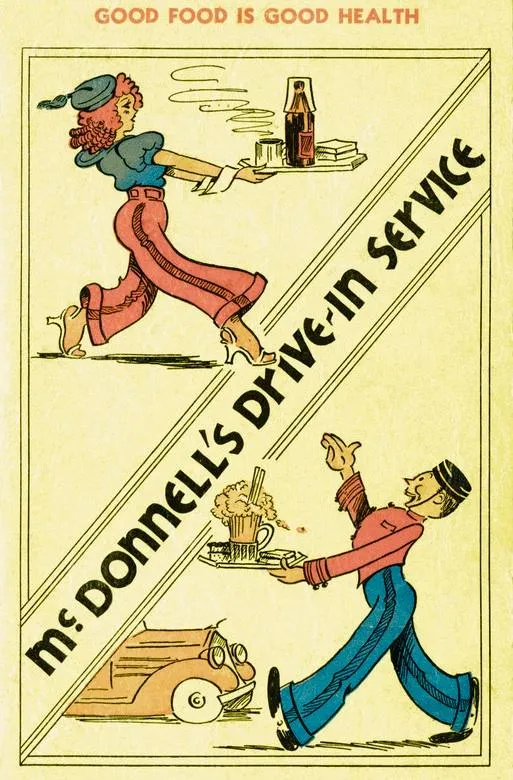

Back then, says McMahon, hamburgers and even a trip to a fast food chain, like McDonnell’s in Los Angeles, was a treat. Serving some of the state’s best fried chicken, the chain actually raised its own chickens on a 200-acre ranch.

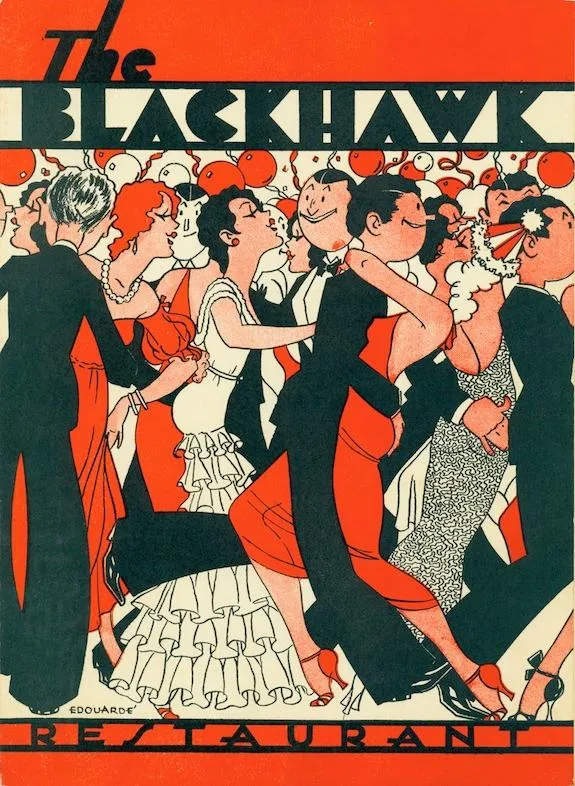

The food wasn’t the only reason to head out. If it was Saturday night in Chicago, you could only be one place: The Blackhawk Restaurant, host of the weekly radio show, “Live! From the Blackhawk!“ Opened in the 1920s, the swinging restaurant hosted Benny Goodman, Glenn Miller, Perry Como and Louis Prima. Beer and McMahon say they like this one for its bold Art Deco graphics:

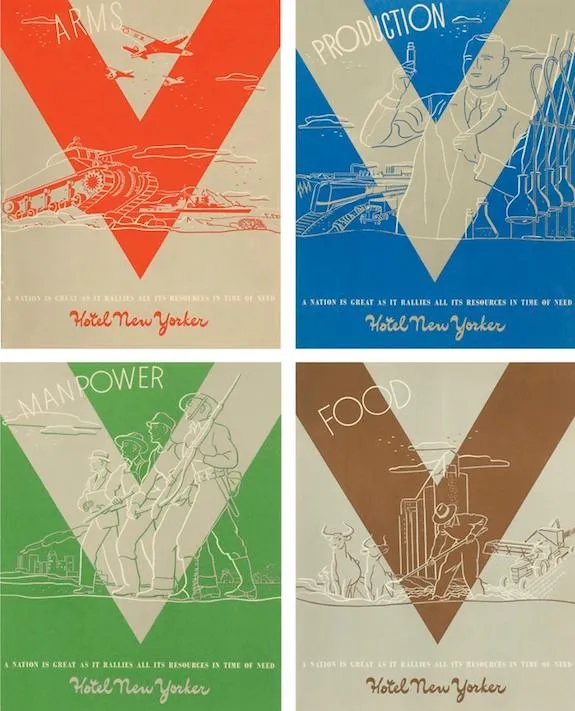

The Hotel New Yorker struck a serious tone with its 1942 menu designs. With four different wartime themes, including “Production” and “Manpower,” the menus spoke to the patriotism of the hotel, which also had its own print shop. The menus reminded visitors that while they may be having a good time in the Big Apple, they shouldn’t forget what’s happening abroad.

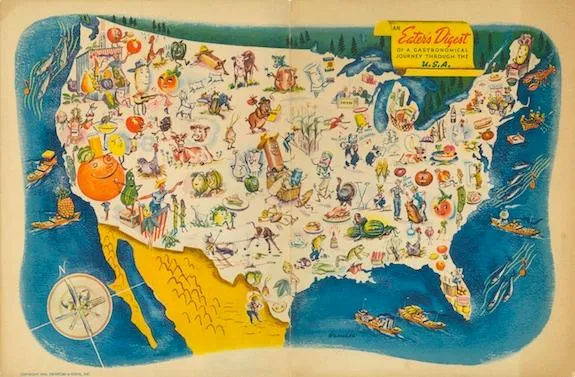

Despite the folksy charm of this 1940s menu from Columbus, Ohio restaurant, the Neil Tavern, the restaurant was actually the premier spot to be seen in the Midwest capital. Part of the stately Neil House hotel, the tavern’s notable diners included Abraham Lincoln and Theodore Roosevelt, Charles Dickens and Oscar Wilde, Amelia Earhart and Eleanor Roosevelt.

Sadly the 600-room establishment was torn down during a 1970s redevelopment project. Beer calls the menu design an incredibly witty ode to American agriculture. But McMahon likes the tiny ships of imported goods, too, including bananas and coffee.

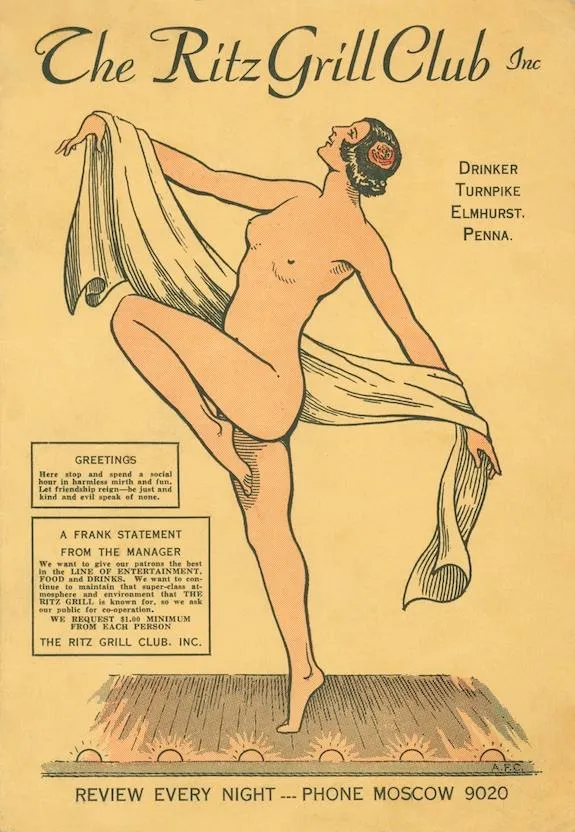

Today, Moscow, Pennsylvania has a population of roughly 2,000. In the 1940s, the borough didn’t even make it on the Census, so it’s a bit of mystery that the town once seemed to host one of the liveliest nights around at the Ritz Grill Club. “Greetings,” reads the 1940s menu cover, “Here stop and spend a social hour in harmless mirth and fun. Let friendship reign–be just and kind and evil speak of none.” And in the interest of providing clients “the best in the line of entertainment, food and drinks” and maintaining “that super-class atmosphere and environment,” the club requested that each patron spend at least $1 for the evening.

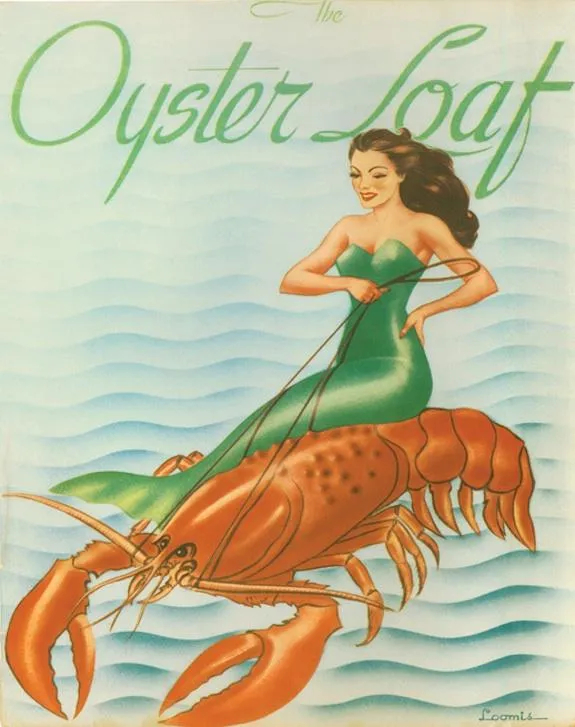

Out on the West Coast, things were even more fantastical. At the Oyster Loaf, mermaids rode side-saddle (naturally) atop giant lobsters, as depicted by artist Andrew Loomis.

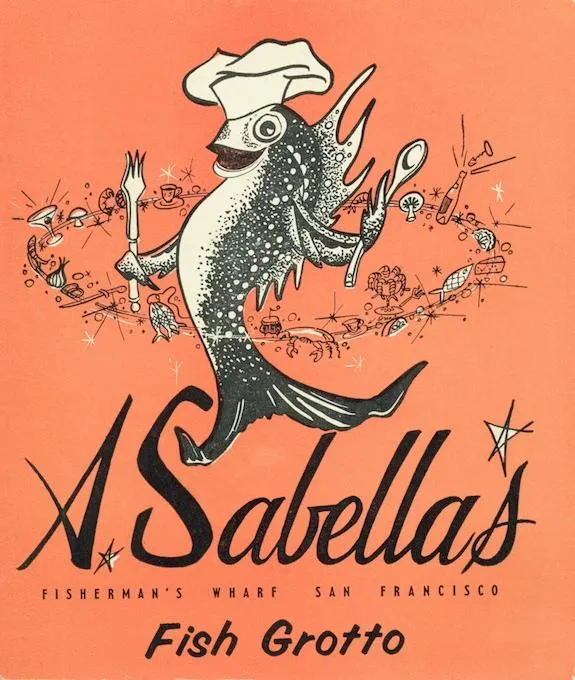

And at A. Sabella’s, fish donned chef’s hats, lipstick and canes for a night out on the Wharf. Opened in 1927 by Sicilian immigrants, the restaurant was run by the same family over four generations before closing in 2007.

Many of the restaurants included in Cool Culinaria’s collection are no longer in business. “A lot of these were family run, independently run and there would come a point in the 1960s and 70s, presumably when the children said, ‘We don’t want to run the restaurant we’re going into advertising or the motor industry or something,’” says Beer.

A. Sabella’s 1959 menu reveals a culinary fish at the center of a swirl of ingredients and utensils. Alongside the plentiful offerings of seafood, the menu also offers “Spaghetti with Italian Sauce.” McMahon says she comes across this a lot; “You see, Italian-style spaghetti, that’s the phrase, especially in the diners. We’re assuming this was long before the average American household used garlic or olive oil in cooking and it probably signifies that the spaghetti in red sauce had been adapted to American palates.”

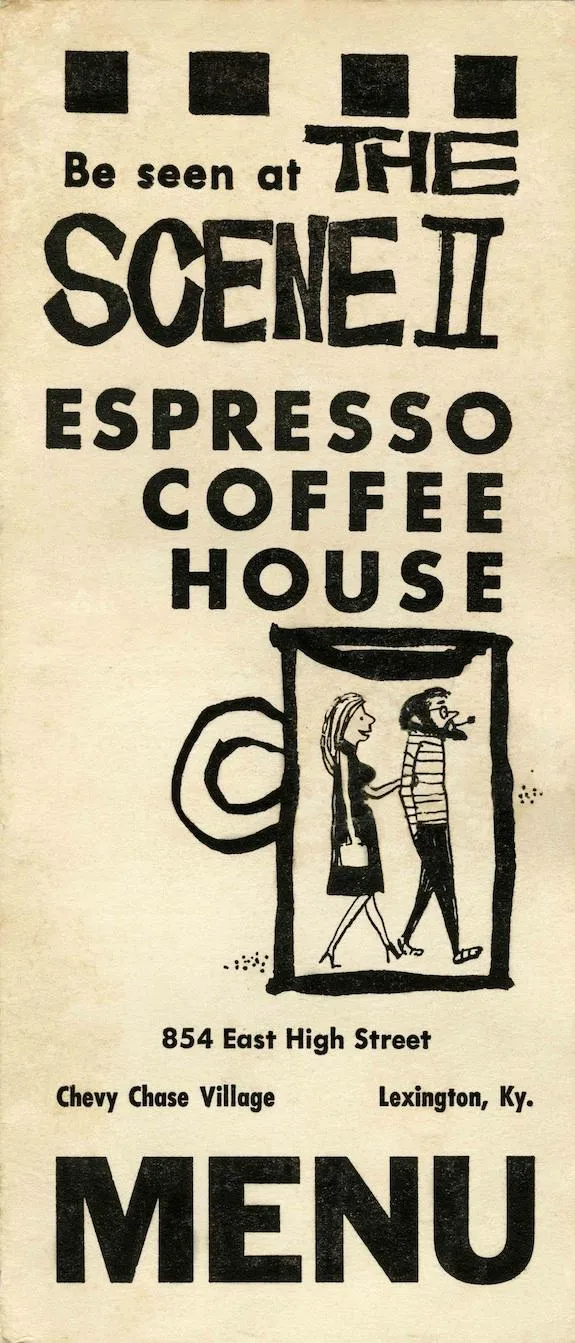

By the 1960s, coffee shops became just as cool a place to be seen as any hip nightclub. Lexington, Kentucky’s coffee house, The Scene II, played on that popularity with its 1960 menu featuring a beatnik couple. “Be seen at The Scene,” reads the cover.

But well before beatniks were growing their hair out and smoking pipes, the real place to be seen was Mexico City’s La Cucaracha cocktail club. “Famous the world over,” the club touted its Bacardi rum and English-speaking personnel for visiting Americans. McMahon suspects, but isn’t sure, those visitors included Ernest Hemingway.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)