7 Ways Technology is Changing How Art is Made

Technology is redefining art in strange, new ways. Works are created by people moving through laser beams or from data gathered on air pollution

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d9/b8/d9b86288-12c0-4d93-95bd-795364577599/pollution_art_final.jpg)

Where would the Impressionists have been without the invention of portable paint tubes that enabled them to paint outdoors? Who would have heard of Andy Warhol without silkscreen printing? The truth is that technology has been providing artists with new ways to express themselves for a very long time.

Still, over the past few decades, art and tech have become more intertwined than ever before, whether it’s through providing new ways to mix different types of media, allowing more human interaction or simply making the process of creating it easier.

Case in point is a show titled “Digital Revolution” that opened earlier this summer in London’s Barbican Centre. The exhibit, which runs through mid-September, includes a “Digital Archaeology” section which pays homage to gadgets and games that not that long ago dazzled us with their innovation. (Yes, an original version of Pong is there, presented as lovable antiquity.) But the show also features a wide variety of digital artists who are using technology to push art in different directions, often to allow gallery visitors to engage with it in a multi-dimensional way.

Here are seven examples, some from “Digital Revolution," of how technology is reshaping what art is and how it’s produced:

Kumbaya meets lasers

Let’s start with lasers, the brush stroke of so much digital art. One of the more popular exhibits in the London show is called “Assemblance,” and it’s designed to encourage visitors to create light structures and floor drawings by moving through colored laser beams and smoke. The inclination for most people is to work alone, but the shapes they produce tend to be more fragile. If a person nearby bumps into their structure, for instance, it’s likely to fall apart. But those who collaborate with others—even if it’s through an act as simple as holding hands—discover that the light structures they create are both more resilient and more sophisticated. “Assemblance,” says Usman Haque, one of the founders of Umbrellium, the London art collective that designed it, has a sand castle quality to it—like a rogue wave, one overly aggressive person can wreck everything.

And they never wet the rug

Another favorite at “Digital Revolution” is an experience called “Petting Zoo.” Instead of rubbing cute goats and furry rabbits, you get to cozy up to snake-like tubes hanging from the ceiling. Doesn’t sound like fun? But wait, these are very responsive tubes, bending and moving and changing colors based on how they read your movements, sounds and touch. They might pull back shyly if they sense a large group approaching or get all cuddly if you’re being affectionate. And if you’re just standing there, they may act bored. The immersive artwork, developed by a design group called Minimaforms, is meant to provide a glimpse into the future, when robots or even artificial pets will be able to read our moods and react in kind.

Now this is a work in progress

If Rising Colorspace, an abstract artwork painted on the wall of a Berlin gallery, doesn't seem so fabulous at first glance, just give it a little time. Come back the next day and it will look at least a little different. That’s because the painting is always changing, thanks to a wall-climbing robot called a Vertwalker armed with a paint pen and a software program instructing it to follow a certain pattern.

The creation of artists Julian Adenauer and Michael Haas, the Vertwalker—which looks like a flattened iRobot Roomba—is constantly overwriting its own work, cycling through eight colors as it glides up vertical walls for two to three hours at a time before it needs a battery change. “The process of creation is ideally endless,” Haas explains.

The beauty of dirty air

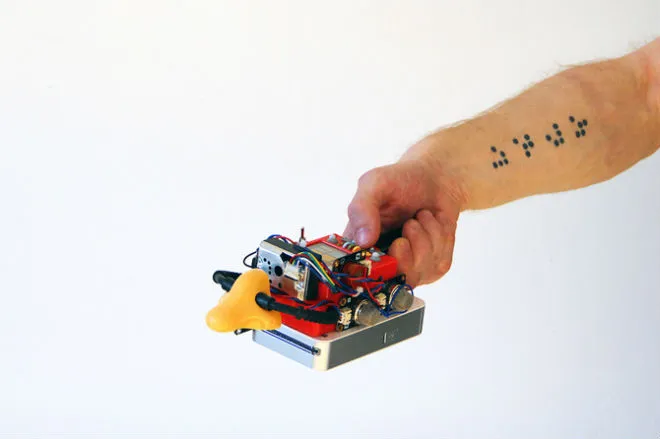

Give Russian artist Dmitry Morozov some credit—he’s devised a way to make pollution beautiful, even if his purpose is to make us aware of how much is out there. First, he built a device, complete with a little plastic nose, that uses sensors which can measure dust and other typical pollutants, including carbon monoxide, formaldehyde and methane. Then, he headed out to the streets of Moscow.

The sensors translate the data they gather into volts and a computing platform called Arduino translates those volts into shapes and colors, creating a movie of pollution. Morozov’s device then grabs still images from the movie and prints them out. As irony would have it, the dirtier the air, the brighter the image. Exhaust smoke can look particularly vibrant.

Paper cuts you can love

Eric Standley, a professor at Virginia Tech, is one artist who doesn’t use technology to make the creation process simpler. Actually, it’s just the reverse. He builds stained glass windows, only they’re made from paper precisely cut by a laser. He starts by drawing an intricate design, then meticulously cuts out the many shapes that, when layered over one another, form a 3-D version of his drawing. One of his windows might comprise as many as 100 laser-cut sheets stacked together. Standley says the technology allows him to feel more, not less, connected to what he’s creating. As he explains in the video above, “Every efficiency that I gain through technology, the void is immediately filled with the question, 'Can I make it more complex?'”

And now, a moving light show

It’s one thing to project laser light onto a stationary wall or into a dark sky, now pretty much standard fare at public outdoor celebrations. But in an art project titled “Light Echoes,” digital media artist Aaron Koblin and interactive director Ben Tricklebank executed the concept on a much larger scale. One night last year, a laser they mounted on a crane atop a moving train projected images, topographical maps and even lines of poetry into the dark Southern California countryside. Those projections left visual “echoes" on the tracks and around the train, which they captured through long-exposure photography.

Finding your inner bird

Here’s one last take from the “Digital Revolution” show. An art installation developed by video artist Chris Milk called “Treachery of the Sanctuary,” it’s meant to explore the creative process through interactions with digital birds. That’s right, birds, and some are very angry. The installation is a giant triptych, and gallery visitors can stand in front of each of the screens. In the first, the person’s shadow reflected on the screen disintegrates into a flock of birds. That, according to Milk, represents the moment of creative inspiration. In the second, the shadow is pecked away by virtual birds diving from above. That symbolizes critical response, he explains. In the third screen, things get better—you see how you’d look with a majestic set of giant wings that flap as you move. And that, says Milk, captures the instant when a creative thought transforms into something larger than the original idea.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/randy-rieland-240.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/randy-rieland-240.png)