A Larger-Than-Life Toussaint Louverture

The Haitian revolutionary joins the Smithsonian Museum of African Art’s collection

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ATM-Object-Ousmane-Sow-631.jpg)

An imposing sculpture by Senegalese artist Ousmane Sow—the centerpiece of a new exhibition, “African Mosaic,” which highlights recent acquisitions at the Smithsonian National Museum of African Art—depicts the 18th-century Haitian revolutionary Toussaint Louverture. The figure, more than seven feet tall, portrays Toussaint reaching out to a seated female slave. “The ‘Great Man’ theory of history is no longer popular,” says curator Bryna Freyer. “But it’s still a way of looking at Toussaint. He really was larger than life.”

The sculpture, which museum director Johnnetta Cole describes as “our Mona Lisa,” evokes two men—the celebrated rebel of Haitian history and the artist who pays homage to him.

In 1743, Toussaint Louverture was born into bondage in Haiti, the French island colony then known as Saint-Domingue, possibly the grandson of a king from what is now the West African nation of Benin. He is thought to have been educated by his French godfather and Jesuit missionaries. Toussaint read widely, immersing himself in writings from the Greek philosophers to Julius Caesar and Guillaume Raynal, a French Enlightenment thinker who inveighed against slavery. In 1776, at the age of 33, Toussaint was granted his freedom from the place he was born, Breda Plantation, but remained on, rising to positions in which he assisted the overseer. He also began to acquire property and achieved a level of prosperity.

In 1791, while France was distracted by the turmoil of the revolution, a slave rebellion began in Haiti. Toussaint quickly got involved; perhaps as repayment for his education and freedom, he helped Breda’s white overseers and their families flee the island. Toussaint (who added Louverture to his name, a reference either to his military ability to create tactical openings or to a gap in his teeth, caused when he was hit by a spent musket ball) quickly rose to the rank of general—and eventually the leader of the independence movement. His forces were sometimes allied with the Spanish against the French, and sometimes with the French against the Spanish and English. In 1799, he signed a trade pact with the administration of President John Adams.

Ultimately, Toussaint considered himself to be French and wrote to Napoleon declaring his loyalty. Bonaparte was neither impressed nor forgiving. In late 1801, he dispatched 20,000 French troops to reclaim the island. Although Toussaint negotiated an amnesty and retired to the countryside, he was seized and sent to a prison in France. There, he died of pneumonia in 1803. In death, as in life, Toussaint was lionized. Wordsworth, no friend of the French, wrote a memorial sonnet, “To L’Ouverture,” attesting to the fallen leader’s enduring fame: “There’s not a breathing of the common wind / That will forget thee.”

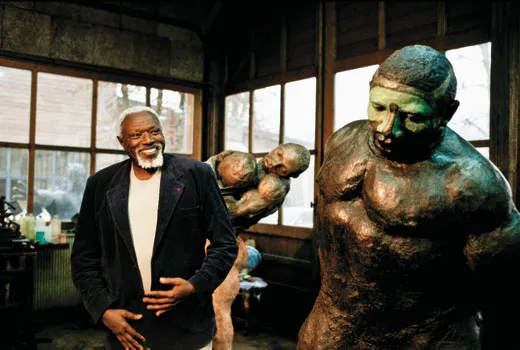

Sculptor Ousmane Sow (rhymes with “go”) created the Toussaint figure in 1989 in Dakar, Senegal. The museum acquired the piece in 2009. Born in 1935 in Dakar, Sow left for Paris as a young man. “He worked as a physical therapist, which gave him a good knowledge of human anatomy,” says curator Freyer. “And he spent hours at Parisian museums, looking at the works of sculptors such as Rodin and Matisse.”

Sow has often chosen historic themes and heroic characters—he has completed a 35-piece work about the Battle of Little Big Horn, a series on Zulu warriors and a bronze statue of Victor Hugo. A large man himself—Sow stands well over six feet tall—the artist seems to favor large-scale pieces. Karen Milbourne, a curator at the museum who has visited Sow’s studio in Senegal, describes an outsize depiction he did of his father. “Because it’s so large and imposing,” she recalls, “it’s as if you’re seeing it [from the perspective of] a child.”

Ordinarily, when discussing sculpture, there is mention of what it’s made of—stone or bronze, wood or terra cotta. Sow works in his own unique medium, creating pieces from a farrago of ingredients that may include soil, straw, cement, herbs and other things, according to an ever-changing recipe. “It’s his secret sauce,” says curator Christine Kreamer. The mixture is allowed to age for weeks or months, and then is applied to a metal framework. According to Freyer, Sow has also used the mysterious substance to waterproof his house.

For his part, Sow doesn’t attempt to define his work’s effect: “I don’t have much to say; my sculptures say it all,” he says.

Owen Edwards is a freelance writer and author of the book Elegant Solutions.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)