A Life Devoted to the American Diner

With a career spent chronicling the best of American diners, curator Richard Gutman knows what makes a great greasy spoon

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/nite-owls-diner-631.jpg)

What Jane Goodall is to chimpanzees and David McCullough is to John Adams, Richard Gutman is to diners. “I was interviewed for a New Yorker article about diners when I was 23 years old,” he says over a meal at the Modern Diner (est. 1941) in downtown Pawtucket, Rhode Island, one recent sunny Monday. “And now, almost 40 years later, I’m still talking about diners.” He’s gradually grown into the lofty title “important architectural historian of the diner” that George Trow sardonically bestowed on him in that 1972 “Talk of the Town” piece, progressing from graduate of Cornell’s architecture school to movie consultant on Barry Levinson’s Diner and Woody Allen’s Purple Rose of Cairo and author of American Diner: Then and Now and other books. But his enthusiasm for his subject remains as fresh as a slab of virtue (diner lingo for cherry pie).

Gutman leaps out of the booth—he’s compact and spry, surprising in someone who’s spent decades not just talking about diners, but eating in them—to count the number of seats in the Modern (52). Weighing the classic diner conundrum—“should I have breakfast or lunch?” he asks the grease-and-coffee-scented air—he boldly orders one of the more exotic daily specials, a fresh fruit and mascarpone crepe, garnished with a purple orchid. Before taking the first bite, like saying grace, he snaps a photograph of the dish to add to the collection of more than 14,000 diner-related images archived on his computer. He tells me that his own kitchen, at the house in Boston where he’s lived with his family for 30 years, is designed diner-style, with an authentic marble countertop, three stools and a menu board all salvaged from a 1940s Michigan diner, along with a 1930s neon “LUNCH” sign purchased from a local antique store. “Nobody has a kitchen like this,” Gutman half-confesses, half-boasts over the midday clatter of dishes and silverware. “Nobody.”

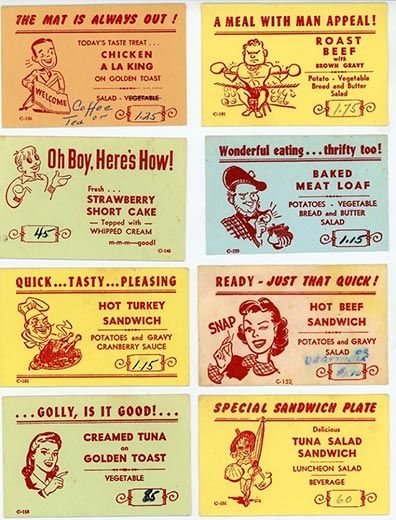

We finish our breakfast/lunch—I highly recommend the Modern’s raisin challah French toast with a side of crispy bacon—and head to Johnson & Wales University’s Culinary Arts Museum in Providence, where Gutman has been the director and curator since 2005. The museum hosts more than 300,000 items, a library of 60,000 volumes and a 25,000-square-foot gallery, featuring a reconstructed 1800s stagecoach tavern, a country fair display, a chronology of the stove, memorabilia from White House dinners and more. But it’s the 4,000-square-foot exhibit, “Diners: Still Cookin’ in the 21st Century,” that is Gutman’s labor of love. Indeed, 250 items come from his own personal collection—archival photographs of streamlined stainless steel diners and the visionaries who designed them, their handwritten notes and floor plans, classic heavy white mugs from the Depression-era Hotel Diner in Worcester, Massachusetts, 77-year-old lunch wagon wheels, a 1946 cashier’s booth. “It’s just one slice of the food service business that we interpret here,” Gutman likes to say, but the diner exhibit is clearly the museum’s highlight.

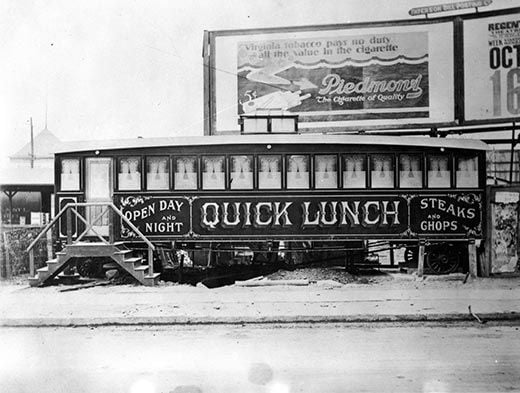

This is fitting, since the history of the diner began, after all, right here in Providence—with a horse-drawn wagon, a menu and, as they say, a dream. In 1872, an enterprising man named Walter Scott introduced the first “night lunch wagon.” Coming out at dusk, the lunch wagons would pick up business after restaurants closed, serving workers on the late shift, newspapermen, theatergoers, anyone out and about after dark and hungry for an inexpensive hot meal. A fellow would get his food from the wagon’s window and eat sitting on the curb. Gaining popularity, the lunch wagons evolved into “rolling restaurants,” with a few seats added within, first by Samuel Jones in 1887. Folks soon started referring to them as “lunch cars,” which then became the more genteel-sounding “dining cars,” which was then, around 1924, shortened to the moniker “diner.”

One distinction between a diner and a coffee shop is that the former is traditionally factory-built and transported to its location, rather than constructed on-site. The first stationary lunch car, circa 1913, was made by Jerry O’Mahony, founder of one of the first of a dozen factories in New Jersey, New York and Massachusetts that manufactured and shipped all the diners in the United States. At their peak in the 1950s, there were 6,000 across the country, as far-flung as Lakewood, Colorado and San Diego, though the highest concentration remained in the Northeast; today, there are only about 2,000, with New Jersey holding the title for most “diner-supplied” state, at 600-plus. New ones are still made occasionally, though, by the three remaining factories, and old ones are painstakingly restored by people like Gutman, who has worked on some 80 diners and currently has a couple of projects going, like the Owl Diner in Lowell, Massachusetts, in the alley (on the side).

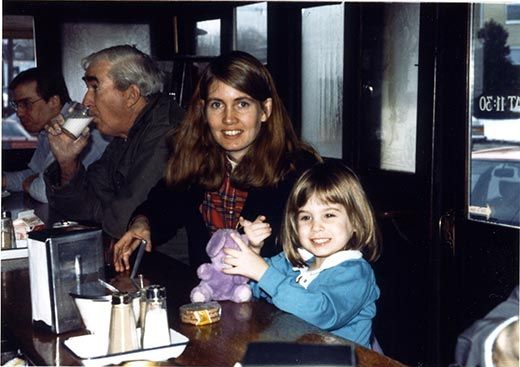

While Gutman is diplomatically reluctant to identify his favorite diner, one of his mainstays is Casey’s of Natick, Massachusetts, the country’s oldest operating diner. “They’ve supported five generations of a family on ten stools,” he says, gesturing to a photograph of the 10-by-20 ½ -half-foot, all oak-interior dining car, constructed as a horse-drawn lunch wagon in 1922, and bought secondhand five years later by Fred Casey and moved from Framingham to its current location four miles away. In the 1980s, when Gutman’s daughter Lucy was little, no sooner had they pulled up to the counter at Casey’s but Fred’s great-grandson Patrick would automatically slide a package of chocolate chip cookies down to Lucy, pour her a chocolate milk, and get her grilled cheese sandwich going on the grill. “If you go to a diner, yes, it’s a quick experience," Gutman explains "But it’s not an anonymous experience.”

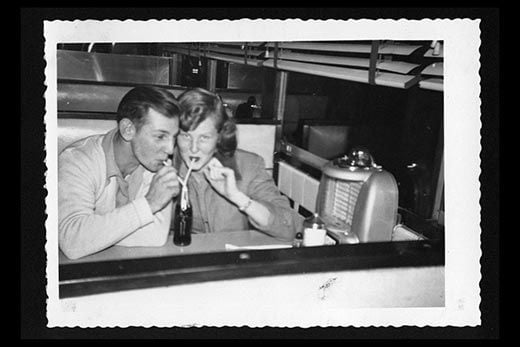

That intangible, yet distinctive sense of community captures what Gutman calls the ordinary person’s story. “Without ordinary people, how would the world run? Politicians have to go to diners to connect. What’s the word on the street? In diners, you get people from all walks of life, a real cross-section.” And while any menu around the country can be counted on for staples like ham and eggs and meatloaf—and, back in the day, pickled tongue and asparagus on toast—a region’s local flavor is also represented by its diners’ cuisine: scrod in New England, crab cakes in Maryland, grits down South.

The changing times are reflected on the diner menu, too: the Washington, D.C. chain Silver Diner introduced “heart-healthy” items in 1989 and recently announced that it would supply its kitchens with locally grown foods; the Capitol Diner, serving the working-class residents of Lynn, Massachusetts, since 1928, added quesadillas to its menu five years ago; today there are all-vegetarian diners and restored early 20th-century diners that serve exclusively Thai food.

If the essential diner ethos is maintained in the midst of such innovations, Gutman approves. But, purist that he is, he’ll gladly call out changes that don’t pass muster. Diners with kitsch, games, gumball machines or other “junk” frustrate him. “You don’t need that kind of stuff in a diner! You don’t go there to be transported into an arcade! You go there to be served some food, and to eat.”

And there you have the simplest definition of what, exactly, this iconic American eatery is. “It’s a friendly place, usually mom-and-pop with a sole proprietor, that serves basic, home-cooked, fresh food, for good value,” Gutman explains. “In my old age, I’ve become less of a diner snob”—itself a seeming contradiction in terms—“which, I think, is probably a good thing.”