A Life Less Ordinary

One of Life magazine’s original four photographers, Margaret Bourke-White snapped shots around the world

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/life_white_388.jpg)

She photographed Gandhi minutes before his assassination, covered the war that followed the partition of India, was with U.S. troops when they liberated Germany's Buchenwald concentration camp, was torpedoed off the African Coast, had the first cover of Life magazine and was the first Western journalist allowed in the Soviet Union.

Margaret Bourke-White, the iconic photographer, didn't just raise the glass ceiling; she shattered it and threw away the pieces.

At a time when women were defined by their husbands and judged by the quality of their housework, she set the standard for photojournalism and expanded the possibilities of being female.

"She was a trailblazer," says Stephen Bennett Phillips, curator at The Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C., who recently mounted a major touring exhibition of Bourke-White's photos. "She showed women that you didn't have to settle for the traditional role."

Bourke-White was fearless, doggedly determined, stylish and so flamboyantly unconventional that "her lifestyle has sometimes overshadowed her photography," Phillips laments.

She lived life her way, living openly with a married man, having affairs with others, putting career above husband and children. But 36 years after her death from Parkinson's, the titillation of her private life pales in comparison to her work.

"She was a photojournalist par excellence," says Phillips, "capturing the human drama, the human condition, in a way that few journalists had been able to capture."

Bourke-White was born in 1904 in New York City—16 years before the 19th Amendment gave American women the right to vote in national elections. Her mother, Minnie Bourke, was a homemaker who had trained as a stenographer; her father, Joseph White, an inventor-engineer-naturalist-amateur photographer who sometimes took his precocious daughter on visits to industrial sites. She would later write in her autobiography, Portrait of Myself: "To me at that age, the foundry represented the beginning and end of all beauty."

She started taking pictures in college (she attended several) using a second-hand camera with a broken lens that her mother bought for her for $20. "After I found a camera," she explained, "I never really felt a whole person again unless I was planning pictures or taking them."

In 1927, after shedding a short-lived marriage and graduating from Cornell University with a degree in biology, she moved to Cleveland, Ohio, an emerging industrial powerhouse, to photograph the new gods of the machine age: factories, steel mills, dams, buildings. She signaled her uniqueness by adding her mother's maiden name to her own.

Soon, her perfectly composed, highly contrasted and dynamic photographs had giant corporate clients clamoring for her services.

"When she began courting corporations, she was one of the few women who were actively competing in a man's world and a lot of the men photographers were very jealous of her," says Phillips. "The rumor got around that it wasn't a woman who was taking the photographs—that it wasn't really her."

Neither her gender nor her age posed a problem for Henry Luce, publisher of Time. In what became a lasting partnership, he hired the 25-year-old Bourke-White for his new magazine, Fortune and gave her almost a free hand. She went to Germany, made three trips to the Soviet Union—the first Western photojournalist to be given access—and traveled all around the United States, including the Midwest, which was experiencing the severest drought in the country's history.

When Luce decided to start a new magazine, he again turned to Bourke-White. One of Life's original four photographers, her picture of Fort Peck Dam in Montana made the first cover on November 23, 1936, when she was 32. Her accompanying cover story is regarded as the first photo essay—a genre, says Phillips, "that would become an integral part of the magazine for the next 20 years."

With the United States in the grips of the Great Depression, Bourke-White undertook a trip through the South with Erskine Caldwell, the famed author of Tobacco Road and God's Little Acre. Their collaboration resulted in a book on Southern poverty, You Have Seen Their Faces. The haggard images staring back at the camera confirmed her "increasing understanding of the human condition," says Phillips. "She became skilled at capturing the human experience."

She and Caldwell moved in together (even though he was married at the time), wed, collaborated on three more books and, although both were passionate advocates of social justice, divorced in 1942. "Mine is a life into which marriage doesn't fit very well," she said.

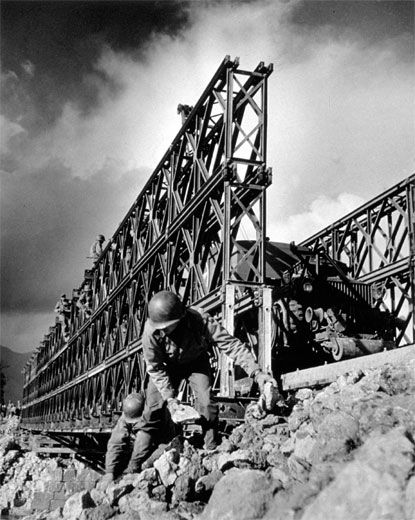

The advent of the Second World War gave her a chance to show her bravery as well as her skill. The first woman accredited as a war correspondent, she crossed into Germany with General Patton, was in Moscow when the Germans attacked, accompanied an Air Force crew on a bombing raid and traveled with the armed forces in North Africa and Italy. To the Life staff she became "Maggie the Indestructible."

But there was grumbling that she was "imperious, calculating and insensitive" and used her unquestionable charm to gain an advantage over her male competitors. Unlike other photographers who had converted to the much lighter 35mm, she lugged around large-format cameras, which, along with wooden tripods, lighting equipment and a developing tank, could weigh 600 pounds. "Generals rushed to carry her cameras and even Stalin insisted on carrying her bags," reported fellow photographer Alfred Eisenstaedt.

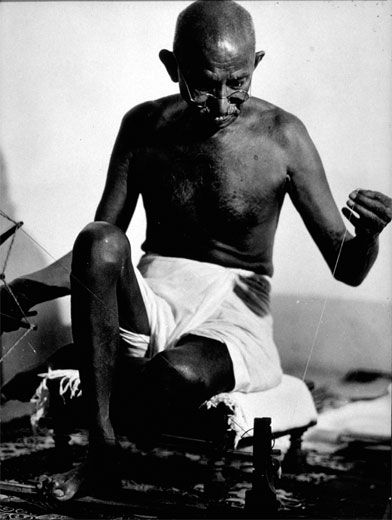

After the war ended, she continued to use her lenses as the eyes of the world, documenting Gandhi's non-violent campaign in India and apartheid in South Africa. Her image of Gandhi at the spinning wheel is one of the best-known photographs in the world. She was the last journalist to see him alive; he was assassinated in 1948, minutes after she had interviewed him.

In 1952, while covering the Korean conflict, she suffered a fall. While seeking a cause for the accident she was diagnosed with Parkinson's, which she fought with the courage she had shown all her life. But two brain surgeries made no difference to her deteriorating condition. With Parkinson's tightening its hold, she wrote Portrait of Myself, an instant bestseller, each word a struggle, according to her neighbors in Darien, Connecticut, who remembered her as a vital younger woman dressed in designer clothes, promenading with a walking stick in the company of her two Afghan dogs.

Life published her last story in 1957, but kept her on the masthead until 1969. A year later, the magazine sent Sean Callahan, then a junior editor, to Darien to help her go through her photos for a future book. She had more and more difficulty communicating, and the last time he saw her, in August 1972, two days before her death, all she could do was blink.

"Fittingly for the heroic, larger than life Margaret Bourke-White," Callahan later wrote, "the eyes were the last to go."

Dina Modianot-Fox, a freelance writer in Washington, D.C. who has worked for NBC News and Greenwich magazine, is a frequent Smithsonian.com contributor