A Lincoln Novel, Native Poetry, Marie Curie and More New Recent Books

In a new alternative history, The Great Emancipator lives to fight a second civil war

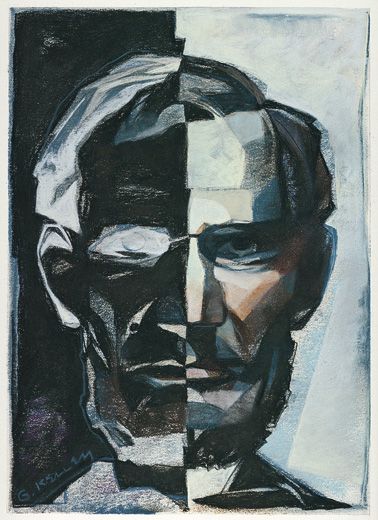

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Books-Abraham-Lincoln-631.jpg)

The Impeachment of Abraham Lincoln: A Novel

by Stephen L. Carter

What if Lincoln had not been assassinated on April 14, 1865, barely a month into his second term? Would he have paid for his attempt to win the Civil War and keep the country unified? Written as a mystery (there’s a conspiracy against Lincoln afoot), this meaty novel tries to sharpen our rosy view of the 16th president. “Lincoln has become so large in our imaginations,” the author writes, “that we might easily forget how envied, mistrusted, and occasionally despised he was by the prominent abolitionists and intellectuals of his day.”

So Carter arranges for Lincoln to be impeached in the Senate for suspending habeas corpus in Maryland, censoring newspapers, failing to protect freed blacks and usurping Congress’s authority. On the first two counts, Lincoln is, as a matter of fact, guilty, as Carter acknowledges. The third and fourth counts are debatable—and intriguing. Would the Great Emancipator have done enough to protect liberated slaves had he survived beyond 1865? Radicals in his own party weren’t sure. President Andrew Johnson, writes Carter, “faced impeachment precisely for carrying out Lincoln’s own ‘let ’em up easy’ policy toward the defeated South.”

A law professor at Yale and the author of the groundbreaking novel The Emperor of Ocean Park, celebrated for its depiction of contemporary middle-class African-American life, Carter here takes plenty of liberties with the historical record—shifting the order of events or inventing them outright—but he has populated his book with real-life figures, often placing real-life speeches in their mouths. At 500-plus pages, it’s a weighty book indeed, and at times feels a bit too much like a con-law text. And there is no shortage of clattering carriage rides, heavy petticoats and other clichés of historical fiction.

But amid the overt conjuring of Washington, D.C.’s past—or Washington City, as it was known in Lincoln’s day—there’s a fresh perspective on the capital’s political and social entanglements, particularly among pthe city’s African-American inhabitants. This is a valuable tonic to the overriding images of 19th-century blacks as universally downtrodden and “grindingly poor.” Dissolute and unfortunate characters appear, but so do upwardly mobile young women, enterprising members of the middle class and truly wealthy African-Americans. Carter’s sustained effort to add nuance to our understanding of Lincoln’s legacy forms the central drama, but I found his quiet readjustment of racial history the more significant thought experiment.

Crazy Brave

by Joy Harjo

The celebrated Native American poet Joy Harjo, author of the American Book Award-winning In Mad Love and War (1990), has not had an easy life. This blunt, moving memoir of her early years is a spare meditation on the conflicts that honed her character and her calling. At 16, her stepfather informed her that he wanted her out of his house. This was no shock to her; he had terrorized her mother and beaten her and her siblings. Harjo contemplated running away—it was the late 1960s and California was calling the flower-power generation—but she instead went to the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, New Mexico. There, Harjo was encouraged to paint, draw and sing—activities that allowed her to escape “the emotional winter of my childhood.” Still, by her late teens she was pregnant and penniless, and her mother, who had “cleaned and cooked her way to decency,” viewed her daughter’s life as “a mockery of her struggle.” But Crazy Brave has a hopeful trajectory, affirming and acclaiming the artistic impulse. “If you do not answer the noise and urgency of your gifts,” Harjo writers, “they will turn on you. Or drag you down with their immense sadness at being abandoned.”

Marie Curie and Her Daughters

by Shelley Emling

“I have frequently been questioned, especially by women, of how I could reconcile family life with a scientific career,” Marie Curie once said. “Well, it has not been easy.” Marie Curie’s accomplishments—two Nobel Prizes, the discovery of radium—are well known, as are her struggles against prejudice, scarce funding and poor health. But her role as a mother has been less examined. She often spent long stretches away from her two children, Irene and Eve. (She tucked math problems into her letters.) As Emling writes, “Marie’s research always took precedence,” and “Eve, in particular, came close to neglect when her girls were quite little.” Still, there seemed no shortage of love among the three women, especially once Marie’s husband, Pierre, died; they formed what Emling calls a female “inner sanctum” of mutual support. The daughters grew up to have remarkable careers. Irene became a Nobel Prize-winning scientist, and Eve a foreign correspondent. This unusually intimate account shows Curie as a precursor of many modern women—bristling at family obligations, hungering for a career. Her sacrifices on behalf of science, Emling seems to say, were worth it; her daughters thrived after all, and the world, because of Curie’s tenacity and ingenuity, became a less mysterious place. “That one must do some work seriously and must be independent, and not merely amuse oneself in life,” said one of Curie’s daughters, “this our mother has told us always.”

Caveat Emptor: The Secret Life of an American Art Forger

by Ken Perenyi

How much is “america’s first and only great art forger,” as the jacket copy describes the author, willing to reveal? Quite a lot, it seems. Perenyi, a graduate of a New Jersey technical school and a Vietnam draft dodger, fell in with a band of artistic New Yorkers and began imitating long-gone masters such as James E. Buttersworth and Martin Johnson Heade. The trick, he learned, was the peripheral details: the materials to which the canvas was fixed, the frame, a faux-aged stain. Perenyi took his canvases to New York antiques shops and specialty galleries, told a tale about a deceased uncle with treasures in his attic, and, more often than not, sold his wares. Some of his paintings reached the upper echelons of the art world and were brokered or bought by famous auction houses. “I never told them the paintings were for real,” Perenyi said to his lawyers in the 1990s, when he found himself at the center of an FBI investigation. “It wasn’t my fault that Christie’s, Phillips, Sotheby’s and Bonhams sold them.” The investigation abruptly ended (the book never makes clear precisely what happened, and the FBI file was marked “exempt from public disclosure,” which may explain the absence of news related to the matter). There are, of course, many morally abhorrent moments in this story—the author is nothing if not disingenuous—but it’s hard not to like this surprisingly entertaining tale of the art world’s shady side. Perenyi is culpable, but he may have had some help from the dealers and auction houses that looked the other way to make a buck.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/books-chloe-schama-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/books-chloe-schama-240.jpg)