A Modern Sherlock Holmes and the Technology of Deduction

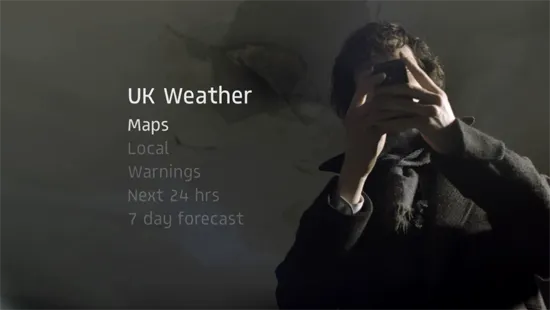

A modern Sherlock Holmes requires a modern tool. Today, his iconic problem-solving magnifying glass has been replaced by the indispensable cell phone

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/bf/59/bf59909d-a8a9-4516-9847-20371c30d68f/sherlock-holmes-search_550.jpg)

In our previous post on the tools that assist Sherlock Holmes in making his astounding deductions, we looked at the optical technologies of the 19th century. Holmes was at the cutting edge of science with his surprising and sometimes disconcerting use of these devices. In Victorian England, he was indeed the most modern of modern men. But what tools would such a man use today? According to Steven Moffat, creator of “Sherlock”, the incredibly successful BBC series that re-imagines Sherlock Holmes in present-day London, the most important tool used by the world’s only consulting detective is his mobile phone.

Yes, the simple mobile phone. Perhaps not as elegant as a well-crafted magnifying glass, but nonetheless suited for solving mysteries in modern London. While the high-tech investigators of “CSI” and similar shows have a bevy of machines available at their disposal, Sherlock Holmes has no need for such resources. Nor is it likely that Sherlock, an independent sort with a collection of social quirks and personal idiosyncrasies (to put it kindly), would have the desire to work within such an organization. Of course, he still has his personal lab and conducts his own experiments in his 221B Baker Street flat, but in this contemporary portrayal, the mobile phone has replaced the iconic magnifying glass as the tool most closely associated with Holmes.

In fact, in the premiere episode of the BBC series, ”A Study in Pink,” Sherlock’s first onscreen “appearance” is in the form of a visualized text message that interrupts a Scotland Yard press conference. One could understand the appeal of the text message to Holmes, as it is purely objective mode of communication; a means to reach a single person or a group of people without having to confront ignorance or recognize any social mores. But of course the phone does much more than send texts.

Many of today’s mobile phones are equipped with GPS devices and digital maps. Sherlock, however, has no use for such features for he has memorized the streets of London. He quickly accesses this mental map while pursuing a taxi through the city’s labyrinthian streets and rooftops. The entire chase is visualized using contemporary digital map iconography. The implication is clear: Sherlock’s encyclopedic knowledge of London is as thorough as that of any computer – and easier to access. Though the specific mode of representation is updated for today’s audience, this characterization keeps true to the original Arthur Conan Doyle stories. In “The Red-Headed League” Holmes tells Watson, “It is a hobby of mine to have an exact knowledge of London.” As we see in Sherlock, an intimate knowledge of streets and houses is as useful in the era of Google maps as it is the time of gas lamps.

In Sherlock viewers are able to watch the eponymous detective conduct web searches via the same unobtrusive, minimal graphics used to represent his text messages. Overlaid onto the scene as a sort of heads-up-display, these graphics let the viewer follow Sherlock’s investigation and learn how his mind works. Although the relevance of his web searches may not always be immediately obvious, such is the fun of watching a detective story unfold. And such is the the wonder of Sherlock Holmes. Today, we all have access to unimaginable amounts of data, but Sherlock’s genius is in how he uses that information.

As with the magnifying glass, the mobile phone merely augments Sherlock’s natural abilities. And, as with the magnifying glass, the mobile phone is so closely associated with Holmes that it becomes, in a way, indistinguishable from the detective. This is made evident when the same onscreen graphic language used to show text messages and web searches is also used to show Sherlock’s own deductive reasoning. In “A Study in Pink,” as Holmes makes his rapid deductions about a dead body, we see his thought process appear onscreen in real-time: the woman is left handed, her jacket is wet but her umbrella is dry, her wedding ring is clean on the inside but scuffed on the outside, the metal has aged. It’s elementary that victim is a serial adulterer in her late 40s. As we follow along with the help of this Holmes-Up-Display, we’re invited to reach the conclusion along with Sherlock but we also get a glimpse of how quickly his mind works.

In the recent Guy Ritiche Sherlock Holmes films, slow motion effects are used to illustrate the speed at which Holmes can think. But in Moffat’s version, the same point is made using the language of digital search technologies. Sherlock thinks as fast as we can google. Probably faster. But there are some things that even Sherlock can’t know. Where, for example, did it recently rain in the UK? For these facts Holmes turns back to the mobile phone –as trusty an ally as Watson– and we see his deductive process continue as he types in his search queries. Graphically, the transition from human thought to web search is seamless. As it did in the 19th century, Sherlock’s use of technology blurs the line between machine and man. Even in a time when Watson has become a “Jeopardy!”-playing supercomputer, Moffat’s Sherlock, like Conan Doyle’s original figure, is still “the most perfect reasoning and observing machine that the world has seen.” With the right tools and the right knowledge Sherlock Holmes, in any era, is a frightfully modern man.

This is the fourth post in our series on Design and Sherlock Holmes. Our previous investigations looked into Sherlock Holmes’s original tools of deduction, Holmes’s iconic deerstalker hat, and the mysteriously replicating flat at 221b Baker Street.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)