A New Taste of Hemingway’s Moveable Feast

The re-edited version of Ernest Hemingway’s Paris-based memoir sheds new light on the heartbreaking breakup of his first marriage

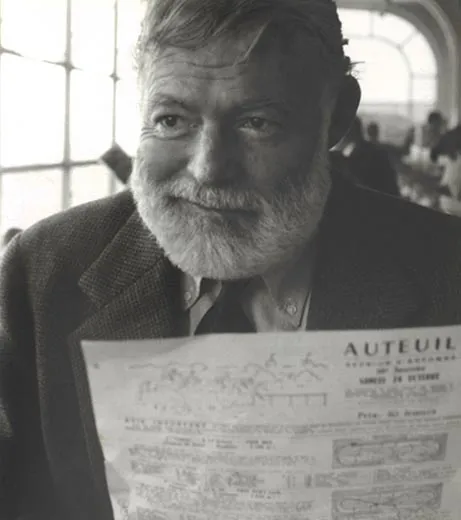

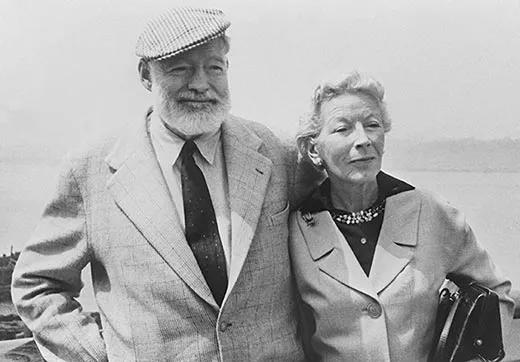

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Ernest-Hemingway-with-wife-Mary-Hemingway-631.jpg)

Ernest Hemingway fans are no strangers to revisions of his life story. “Hemingway, Wife Reported Killed in Air Crash,” a New York newspaper declared seven years before he died. Hemingway read the announcement with amusement while recovering from serious but nonfatal injuries sustained in said crash.

Despite many biographies about the author, revelations about his life continue to make news. A few weeks ago, a new book, Spies: The Rise and Fall of the KGB in America, revealed that Hemingway was recruited as a spy in 1941 and met with Soviet agents in London and Havana. (Hemingway— agent “Argo”—never delivered any “political information,” according to the book.) Early this year, a new digital archive of documents and photographs salvaged from the basement of the author’s moldering home near Havana became available, and it promises a wealth of revealing tidbits.

But perhaps the most significant revision to Hemingway’s legacy comes from his own pen. Scribner recently published a “restored edition” of the author’s posthumous fictionalized memoir, A Moveable Feast. The original book was edited and given its title by Hemingway’s fourth wife, Mary, three years after Hemingway committed suicide in Ketchum, Idaho, in 1961. The new version claims to be “less edited” and “more comprehensive” than the previous, laying out the material “the author intended.” It is based on “a typed manuscript with original notations in Hemingway’s hand—the last draft of the last book that he ever worked on,” Sean Hemingway, the author’s grandson, wrote in the book’s preface.

The project was proposed by Patrick Hemingway, the son of Hemingway and Pauline Pfeiffer, the author’s second wife. There has been speculation that the revision was motivated, at least in part, by Patrick’s desire to present his mother in a more positive light. In the original version, Hemingway’s first wife, Hadley, is the undeniable hero; Pauline is the conniving interloper, befriending the lonely wife while the husband is busy working.

When Hemingway returns to his first wife and son after an illicit rendezvous with Pauline in the first version, he poignantly describes the regret that Hadley’s presence awakens: “When I saw my wife again standing by the tracks as the train came in by the piled logs at the station, I wished I had died before I ever loved anyone but her. She was smiling, the sun on her lovely face tanned by the snow and sun, beautifully built, her hair red gold in the sun, grown out all winter awkwardly and beautifully, and Mr. Bumby standing with her, blond and chunky and with winter cheeks looking like a good Vorarlberg boy.” Although this was clearly an important event, Hemingway did not include this episode in his final manuscript. Mary Hemingway was the one who placed this passage near the close of the book, where it delivers a sense of haunting finality—a glimpse of a paradise lost.

The new version reorders the chapters and includes several additional vignettes, in a separate section titled “Additional Paris Sketches," that provide a more comprehensive account of the breakup of his marriage with Hadley and the start of his relationship with Pauline. The passage quoted above is moved to this section, and there is an extended discussion of the “pilot fish” (John Dos Passos), who supposedly introduced Hemingway to a dissolute, rich crowd, greasing the wheels for his infidelity. But rather than salvage Pauline, the details in the additional material actually make the painful disintegration of the marriage more pronounced and absorbing.

According to other accounts, after Hadley discovered their romance, she insisted that Hemingway and Pauline separate in order to determine if their passion would diminish with distance. Pauline returned to her family in Arkansas; Hemingway stayed in Paris. The distance did not cool Hemingway’s desire. “All I want is you Pfife,” he wrote to her, “and oh dear god I want you so.” But neither did it diminish his guilt: “And I’m ashamed of this letter and I hate it.” Hadley—justifiably—did not excuse her wayward husband. “The entire problem belongs to you two,” she wrote to him during this period. “I am not responsible for your future welfare—it is in your hands.”

More than a reappraisal of Pauline, the restored version of A Moveable Feast is an illustration of the torture Hemingway felt over loving two women at once. “You love both and you lie and hate it,” Hemingway writes, “and it destroys you and every day is more dangerous and you work harder and when you come out from your work you know what is happening is impossible, but you live day to day as in a war.” In a section of the book called “Fragments”—transcriptions of Hemingway’s handwritten drafts—there is an anguished reiteration of this. “I hope Hadley understands,” Hemingway wrote, eight times, with only minor variation.

After one of his early short stories, “The Doctor and the Doctor’s Wife,” was published, Hemingway wrote to his father: “You see I’m trying in all my stories to get the feeling of the actual life across—not to just depict life—or criticise it—but to actually make it alive.” The profession may have been a backhanded apology for a story that many think skewered his father’s misguided sense of authority, but it could just as easily be applied to A Moveable Feast. Hemingway continued, telling his father that he wanted to make his readers “actually experience the thing. You can’t do this without putting in the bad and the ugly as well as what is beautiful.” Readers have long experienced the beautiful side of 1920s Paris—the Dôme Café, Shakespeare and Company, the bars of the Left Bank—through A Moveable Feast. Now, with a little more of the bad and the ugly, “the feeling of actual life” comes into even sharper relief.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/books-chloe-schama-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/books-chloe-schama-240.jpg)