“A Precise, Beautiful Machine”: John Logan on Writing the Screenplay for Hugo

The Oscar-nominated writer tells how he adapted Brian Selznick’s bestseller for the screen

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20120224102109Hugo-duo-thumb.jpg)

With 11 Oscar nominations and a slew of other awards, Hugo is one of the most honored films of 2011. “Everything about Hugo to me is poignant,” screenwriter John Logan told me. “From the broken orphan to the old man losing his past to the fragility of film itself.”

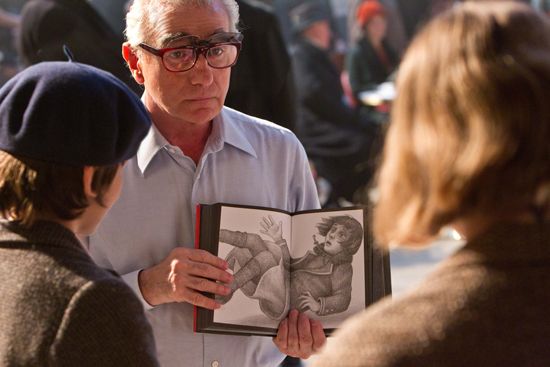

The story of a young orphan who lives in a Paris train station and his momentous discoveries, Hugo marks director Martin Scorsese’s first film for children, and his first using 3D. The movie was based on Brian Selznick’s bestselling novel The Invention of Hugo Cabret. Hugo: The Shooting Script has just been published by Newmarket Press/It Books. Along with Logan’s script, the book includes photos, full credits, and production notes.

Mr. Logan took time out from his intimidatingly busy schedule to speak by phone about working on Hugo. “The reason we all made the movie is because we loved Brian’s book,” he says. “It works on so many levels—as a mystery story, an adventure novel, an homage to cinema. The challenge in adapting it was keeping tight control over the narrative. Because despite the 3D and the magnificent special effects and the sets and the humor and the sweep and grandeur of it all, it’s actually a very austere and serious story. Secondary to that, and this part really was challenging, was hitting what I thought was the correct tone for the piece.”

Since Selznick’s book was a 500-page combination of text and illustrations, Logan had to eliminate some characters and plot strands to fit the story into a feature-film format. “Also there were things we added,” says Logan. “We wanted to populate the world of the train station. What Marty and I talked about was Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window and Sous les toits de Paris (Under the Roofs of Paris) by René Clair. Like those films, we wanted Hugo’s world to be filled with characters, and I had to write vignettes to dramatize them. Particularly the Station Inspector, played so memorably by Sacha Baron Cohen. We wanted to build that character up to be more of an antagonist to Hugo, so I did a lot of work there.”

Film history is a key element in Hugo, whose plot hinges on early French cinema. And as part of his homage to older styles, Logan incorporated as many cinematic devices as he could. Hugo has voice-over narration, flashbacks, a dream-within-a-dream segment, silent sequences, flip animation, and even scenes that recreate early 20th-century filmmaking techniques. “We tried to suggest all the different ways of telling a story on film,” Logan explained. “Even the trickiest devices in the world, like the nightmare within a nightmare, which is straight out of Hammer horror films. We wanted Hugo to be a cornucopia of cinema, a celebration of everything we do in movies.”

Writing silent scenes as opposed to those with dialogue was “almost like using two different parts of the brain,” Logan said. One part “writes description, which is prose and relies on adjectives, leading a reader and a moviegoer through the action in a sort of kinetic way. The other part of your brain writes dialogue, which has to find the perfectly chosen phrase with just enough syllables, not too much, the appropriate language for the individual character in the individual scene to express what’s going on.”

I found the flashbacks in Hugo especially intriguing and asked Logan to show how he found entry and exit points into the past for a scene in which Hugo remembers his father. “The danger is, if you leave the present narrative for too long and get engaged in a narrative in the past, you’ll have to jump start getting back into the reality of the present,” he says. “And always you want to follow Hugo’s story. So going into the memories about his father, I had him looking at the automaton—which is also when we reveal it to the audience for the first time—and Hugo thinking about the genesis of the machine and therefore his relationship with his father. The transitions for me were always about what Hugo is thinking and feeling.”

Like the clocks, toys, and projectors within the story, Hugo is itself “a precise, beautiful machine”—which is how Logan introduces the train station in his script. For Scorsese and his crew it was an immense undertaking. (One traveling shot through the station early in the film took over a year to complete.) When Logan began work on the project, the director hadn’t decided to use 3D yet. But the author insisted that technical considerations didn’t impact his writing.

“That’s just not the way I work or the way Marty Scorsese works,” Logan argued. “I wrote the script I needed to write to tell the story to be true to the characters, and the technical demands followed. The reality of filmmaking, of bringing a script to life, which are the technical requirements, follow. So I never felt limited in any way to write any particular way.”

Still, some changes to the script were made on the set. “Marty is pretty faithful in shooting,” he says. “But he’s also very generous with actors in exploring different avenues and different ways of expressing things. And of course Marty Scorsese is the world’s greatest cineaste. In his head he carries an archive of practically every film ever made. When we were working, astounding references would sort of tumble out of him.”

I use intimidating to describe Logan not just for his skill, but his working habits. In addition to adapting the Broadway hit Jersey Boys for movies, he is collaborating with Patti Smith on a screen version of her memoir Just Kids, and has completed the script for the next James Bond film, Skyfall. In addition to Hugo, last year saw releases of two more of his screenplays, Rango and Coriolanus, adding an Oscar-nominated animated feature and a challenging Shakespeare adaptation to his credits.

It’s just “kismet” that all three films came out in 2011, Logan thought. “Movies achieve critical mass at completely different times for a hundred different reasons,” he added. “You know I’ve been working on Hugo for over five years, and it just happened to come out when it did because that’s when we got the budget to make it, post-production costs took a certain amount of time, this release date was open. But it just as easily could have opened this year depending on any of those factors. Any pundit who says, ‘Well this is a big year for nostalgia about Hollywood’ because Hugo and The Artist are coming out at the same time knows nothing about movies.”

At its heart, Hugo is about broken people seeking to become whole—a consistent theme throughout Logan’s work over the many styles and genres he has mastered. He has written about painter Mark Rothko (the play Red), Howard Hughes (The Aviator), and the demon barber himself in Tim Burton’s version of the musical Sweeney Todd. “Yeah, I’m not interested in characters who aren’t broken,” he said. “I’m not interested in happy people. It just doesn’t draw me as a writer. Theater people say you are either a comedian or a tragedian, and I’m a tragedian. And the vexing, dark characters, the ones where I don’t understand their pain or their anguish, they are the characters that appeal to me.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/daniel-eagan-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/daniel-eagan-240.jpg)