A Serious Look at Funny Faces

A history of caricatures exposes the inside jokes

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Arts-Infinite-Jest1-hero.jpg)

It was not entirely a laughing matter to tour the recent exhibition Infinite Jest: Caricature and Satire from Leonardo to Levine at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. While not an overwhelmingly large show (comprising 160 items), it covered the entire history of caricature from the Italian Renaissance to the present, providing an excellent survey of the subject. Jokes from a century or more ago can be quite difficult to understand. To grasp why they’re funny is often hard work.

Fortunately, the show has a well-written catalog by its curators, Constance McPhee and Nadine Orenstein, which led me smoothly through the challenging material. Of all the catalogues I’ve acquired lately, this one has been the most fun to read. At once erudite and entertaining, it lays out a wonderfully succinct and enjoyable account of a seemingly esoteric subject.

The History of Caricature

The modern art of caricature—that is, the art of drawing funny faces that are often distorted portraits of actual people—traces its roots back to Leonardo da Vinci, although we don’t know whether Leonardo’s “caricatures” of handsome and ugly heads were intended to be funny or were made as quasi-scientific investigations of the deforming effects of age, and of the forces that generate these deformations.

The word “caricature,” which fuses the words carico (“to load”) and caricare (“to exaggerate), was first used in the 1590s by the Carracci brothers, Agostino and Annibale, to apply to pen drawings of distorted human heads—generally shown in profile and arranged in rows to show a progression.

Caricature in the modern sense seems to have been created by Gian Lorenzo Bernini. He was apparently the first to create satirical drawings of recognizable people. Interestingly, he seems to have somehow turned this art into a backhanded form of flattery, similar to the celebrity roasts of today. Being important enough to satirize was proof of one’s importance.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, the art form developed as a curious mix of the crude and obvious, and the obscure and arcane. At one level, it reduces the language of visual expression to its most uncultured elements, and certain devices seem to be repeated almost endlessly: exaggerated faces, processions of funny-looking people, people with faces like animals, and a good deal of bathroom humor.

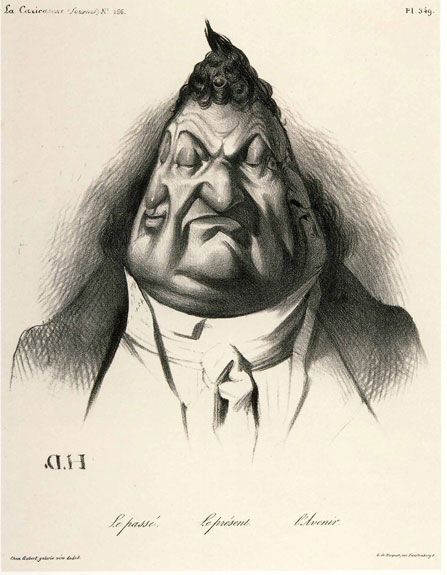

At the same time, drawings in which individuals were caricatured often contained sophisticated puns and in-jokes, rooted in wordplay. Perhaps the most famous examples of this are the series of lithographs by Honore Daumier from the early 1830s representing King Louis-Philippe in the form of a pear. The monarch’s face, with its large jowls, was pear-shaped, and so was his rotund body. In French slang the word for pear, le poire, was also a colloquial term for “simpleton.” Also the king’s initials, L. P., could be read Le Poire. The basic visual trope communicates its message clearly, even if we don’t grasp the wordplay. We can gather that the king was being ridiculed for being sluggish and obese. In many instances, however, particularly with political satire, this sort of punning became almost deliberately arcane, rather in the fashion of the iconography of medieval saints.

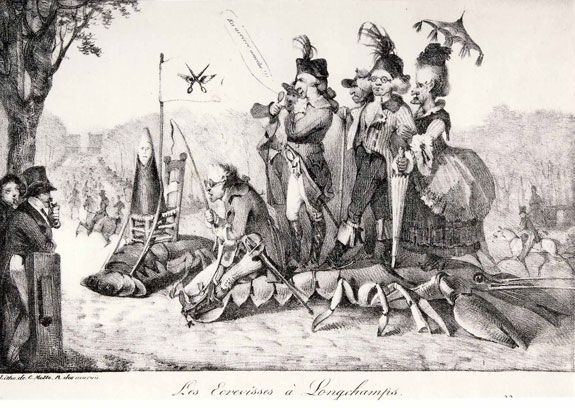

An early print by Eugene Delacroix ridicules censorship of the press by reactionary monarchists with a representation of the famous horse race at Longchamps being run by crayfish carrying a surreal set of riders. One crayfish carries a sugar loaf (le pain de sucre), which represents a censor named Marie-Joseph Pain; another carries a chair (la chaise), which stands for the censor La Chaize. Why are they riding crayfish? Because they are mounts “perfectly suited to these men who never rose to any heights and usually walked backward,” according to a long explanatory text accompanying the image, published April 4, 1822, in the leftist newspaper Le Miroir. Careful study of the print reveals that nearly every element contains a pun or political allusion. The unfinished Arc de Triomphe in the background stands for the liberal ideology that the censors were trying to displace.

Many of the key figures in the history of caricature were great masters of “high art” as well: Leonardo, Bernini, Delacroix, Pieter Breughel the Elder, Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo, William Hogarth, Francesco de Goya, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Claude Monet and others. But many remarkable caricatures were produced by artists who are not well-known; and the form also produced an interesting set of specialists, such as James Gillray, Thomas Rowlandson and George Cruikshank, who made caricatures and very little else. Thus, the challenge of writing a history of caricature makes us rethink what art history is all about: both how to describe its major developments and who to consider a figure of importance.

The Print Room at the Metropolitan

The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s remarkable collection of prints and drawings is much larger and far more comprehensive than any other in the United States. It has about 1.2 million prints and 12,000 illustrated books. It contains a vast assortment of prints that most art museums would not bother to collect: ornamental prints, costume plates, broadsides, political broadsides and even baseball cards. Therefore the museum could assemble an exhibition of caricature, including popular prints, of a sort impossible to assemble anywhere else in America. There are autograph drawings by major masters and remarkable prints by figures such as Francois Desprez (French) and Henry Louis Stephens (American), who are obscure even to specialists in French or American art.

The History of Caricature: Caricature and Democracy

Facing a sprawling topic, the curators chose to organize the exhibit following four themes, with content within each category arranged chronologically. The first section explored exaggeration as it developed over time, starting with deformed heads and developing to strange distortions of the body as a whole, including peculiar creations in which human features merge with those of animals, or take the form of fruits and vegetables, piggybanks, moneybags and other objects. The show then moved on to social satire, much of it focused on costume or obscene humor; political satire, which often has narrative references related to the literature and political writing of a period; and celebrity caricature, a genre that emerged in the late 19th century, and reached its peak in the 20th in the work of figures such as Ralph Barton, Al Hirschfeld and the famous singer Enrico Caruso.

What’s nice about this scheme is that it allowed me to move quickly and easily from observations about the general history of caricature to detailed entries on the individual works. The scheme also carried some theoretical implications. Surprisingly little has been written about the “theory” of caricature: In fact, only two writers have focused seriously on such questions, both Viennese art historians, Ernst Kris and Ernst Gombrich. They were chiefly interested in the expressive nature of caricature and considered it from a psychological perspective—either under the influence of Freud, whose theories shed light on some of the deep emotional roots of caricature, or under the influence of Gestalt psychology, which provided clues about how we draw meaning by collecting clues from expressive visual fragments.

What McPhee and Orenstein bring out is the social aspect of the art form, which has a strong element of performance and seems to depend on the existence of a specialized audience.

Caricature requires an audience and the modern mechanisms of marketing, production and political and social communication. To a large degree, in fact, it seems to be allied with the emergence of modern democracy (or of groups within an autocratic system that function in a quasi-democratic way), and it seems to thrive in cultural sub-groups that are slightly estranged from the social mainstream. At times, in fact, caricature appears to evolve into a sort of private language that affiliates one with a particular social group. The ability to tolerate and even encourage such ridicule seems to mark a profound cultural shift of some sort. Generally speaking, totalitarian despots don’t seem to delight in ridicule, but modern American politicians do. Like the detective story, which did not exist until the 19th century, and seems to thrive only in democratic societies, the growth of caricatures marks the emergence of modern society, with its greater tolerance for diversity of opinion and social roles.

Cartooning, Cubism, and Craziness

Did I have criticisms of the exhibition? I have several, although to some degree they’re a form of flattery, for they show the project opened up major questions. My first criticism is that to my mind the show defined caricature too narrowly; it left out art forms that are clearly outgrowths of caricature, such as comic books, the funny papers, animated cartoons and decorative posters that employ a reductive drawing style. From the standpoint of creating a manageable show, this was surely a sensible decision. Indeed, what’s wonderful about the show and the catalog was the clarity and focus of its approach—the way they reduced the entire history of caricature to a manageable number of examples. But at the same time, this shortchanged the significance of caricature and separated its somewhat artificially from the history of art as a whole.

This first criticism leads to my second. The show failed to explore the fascinating ways in which caricature—as well as “cartooning”—were surely a major force in the development of modern art. The drawings of Picasso and Matisse, for example, moved away from the sort of “photographic realism” taught in the academy to a form of draftsmanship that was more cartoonlike—and that can still sometimes appear “childish” to people who feel that images should translate the world literally.

Some of Picasso’s most important early Cubist paintings—his portraits of Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, Ambroise Vollard and Wilhelm Uhde—are essentially caricatures, one step removed from the celebrity caricatures of figures like Max Beerbohm and Marius de Zayas. One might even argue that Cubism was fundamentally an art of caricature—an art of representing things through distortions and “signs,” rather than more literal but more lifeless forms of representation. Could it be that “caricature” lies at the heart of modern art?

My final criticism raises issues that are even more daunting. While the works included in the show were delightful, the curators sidestepped one of the fundamental aspects of caricature—that it has an edge of nastiness that can easily lead into prejudice and bigotry. It often veers into ethnic and racial stereotyping, as in the caricatures of Irish-Americans by Thomas Nast or African-Americans by Edward Kemble. At its extreme, think of the Jewish caricatures created by Nazi German cartoonists—which surely played a role in making possible the Nazi death camps.

One can sympathize with the organizers of this exhibition sticking to the quaint political squabbles of the distant past and for avoiding this sort of material: After all, they didn’t want their show to be closed down by picketers. I frankly don’t know how such material could have been presented without causing offense on somebody’s part, but without it, a show of caricature feels a little muted. Caricature is a dangerous art.

It’s precisely that delicate line between what’s funny and what’s not acceptable that makes caricature so powerful. Caricature has often been a mighty tool for fighting stupidity and injustice. But it also has been used in the service of bigotry. A comprehensive history of caricature would more deeply explore some of the ways that this art form has a wicked aspect and connects with the dark corners of the human soul.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/henry-adams-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/henry-adams-240.jpg)