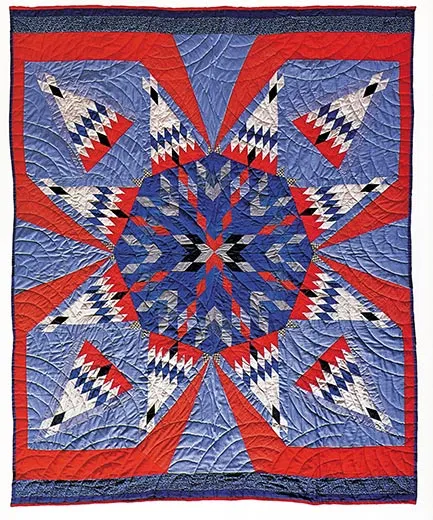

A Spectacular Collection of Native American Quilts

Tribes from the Great Plains used quilts as both a practical replacement of buffalo robes and a storytelling device

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Almira-Jackson-American-Indian-quilt-631.jpg)

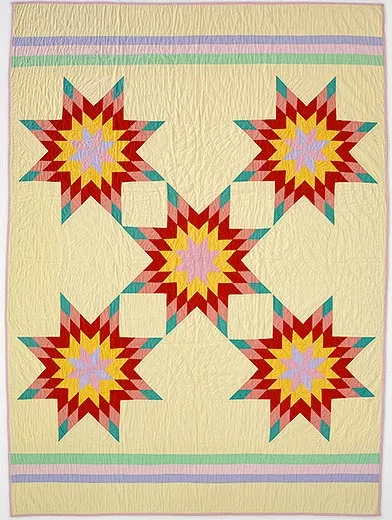

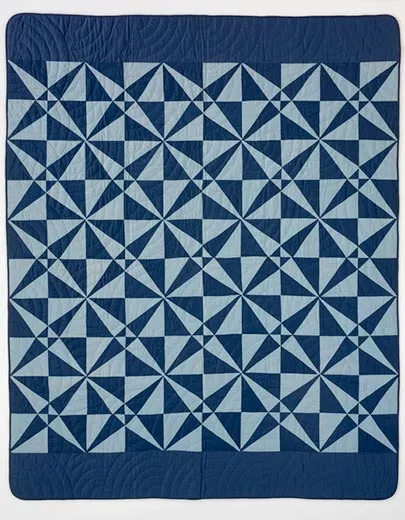

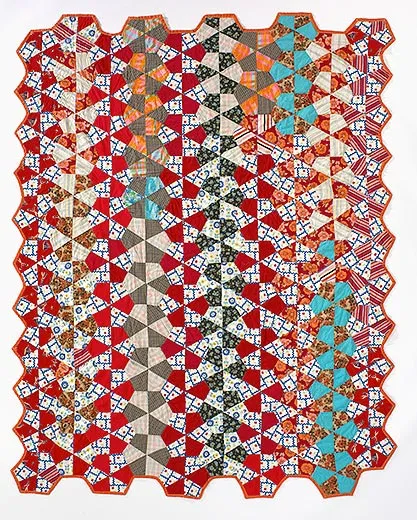

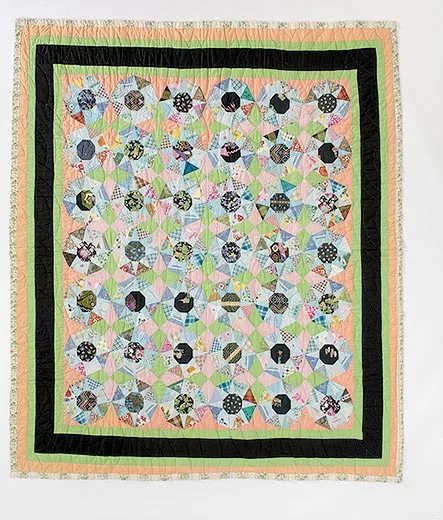

American Indians have long been recognized for their superb artistry and craftsmanship, creating woven rugs and blankets, beadwork, basketry, pottery, ceremonial clothing and headdresses prized by collectors. But the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) is home to one of the largest collections of a Native American art form that is hardly known at all: the quilt. Eighty-eight quilts—stitched by women from the Northern Plains tribes from the 1940s on—were acquired in 2007 from a spectacular collection put together by Florence Pulford.

Pulford, a San Francisco Bay area homemaker, first got interested in quilts of the Plains tribes in the 1960s. According to NMAI curator Ann McMullen, these quilts—many bearing a central octagonal star—functioned as both ritual and practical replacements for Plains Indians buffalo robes. Bison hides had grown scarce as herds were hunted nearly to extinction in a campaign to subdue the Plains tribes during the late 1800s. Missionary wives taught quilting techniques to Indian women, who soon made the medium their own. Many of the patterns and motifs, McMullen says, “have a look very similar to [designs painted on] buffalo robes.”

Some of the quilts, including a highly pictorial piece entitled Red Bottom Tipi (Story of the Assiniboine), tell stories. Its dark blue stripe represents the Missouri River; figurative images depict the tepees of an Assiniboine camp and its inhabitants. But most of the Pulford quilts feature abstract geometric patterns. The museum bought 50 quilts from Pulford’s daughters, Ann Wilson and Sarah Zweng, who also donated an additional 38.

Wilson recalls the genesis of the collection: “Since the 1940s, my father, a doctor, and my mother, and later the kids, went to a wonderful camp, a working ranch, Bar 717, in Trinity County in northern California,” she says.

In the 1960s, Frank Arrow, a Gros Ventres Indian, came to Bar 717 from Montana to work with the horses and befriended Pulford and her family. “In 1968,” says Wilson, “Frank’s aunt invited my mother to come to the Fort Belknap Reservation in Montana.” On that first visit, Pulford, who had a long-standing interest in Native American culture, was invited to a powwow and was given a quilt as a gift.

“My mother was stunned by the poverty on the reservation, as I was when I spent a summer [there] at the age of 21,” Wilson says. “She saw that the quilts were made using feed sacks and other bits and pieces of material. She decided that these artists deserved better materials.” Pulford began buying fabric in California and sending it to artisans at Fort Belknap, Fort Peck and other Montana reservations, sometimes even driving a horse trailer packed with quilting materials.

Pulford also began selling the quilts, using proceeds to buy additional fabric and turning over the remaining profit to the quilters. “This was the first time many of the women on the reservations had ever made any money,” Wilson recalls.

It was during one of Pulford’s early trips to Montana that she met quilter Almira Buffalo Bone Jackson, a member of the Red Bottom band of the Fort Peck Assiniboine. The two women became fast friends, staying close until Pulford’s death at age 65 in 1989. “Besides their many visits,” says Wilson, “my mother and Almira kept up a long, very intimate correspondence. They wrote about my mother’s health, about Almira losing her husband, all sorts of things.” Twenty-four of the quilts in the NMAI collection, including Red Bottom Tipi, were designed and sewn by Jackson, who died in 2004 at age 87.

“Almira was also a very talented artist in other ways,” says McMullen. In Morning Star Quilts, Pulford’s 1989 survey of quilting traditions among Native American women of the Northern Plains, she tells of a letter she got from Jackson that described a single month’s output: a baby quilt, two boy’s dance outfits, two girl’s dresses, a ceremonial headdress and a resoled pair of moccasins. “Almira was also well known for other traditional skills,” McMullen says. “Florence was especially intrigued by her methods for drying deer and antelope and vegetables for winter storage.”

Which raises, it seems, an interesting question. In the world of fine art, how many gifted artists can count a working knowledge of curing meat among their talents?

Owen Edwards is a freelance writer and author of the book Elegant Solutions.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)