A Velázquez in the Cellar?

Sorting through old canvases in a storeroom, a Yale curator discovered a painting believed to be by the Spanish master

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Velazquez-The-Education-of-the-Virgin-631.jpg)

John Marciari first spotted the painting among hundreds of other works carefully filed in pullout racks in a soulless cube of a storage facility in New Haven, Connecticut. He was then, in 2004, a junior curator at Yale University’s renowned Art Gallery, reviewing holdings that had been warehoused during its expansion and renovation. In the midst of that task, he came upon an intriguing but damaged canvas, more than five feet tall and four feet wide, which depicted St. Anne teaching the young Virgin Mary to read. It was set aside, identified only as “Anonymous, Spanish School, seventeenth century.”

“I pulled it out, and I thought, ‘This is a good picture. Who did this?’” says Marciari, 39, now curator of European art and head of provenance research at the San Diego Museum of Art. “I thought this was one of those problems that just had to be solved. It seemed so distinctive, by an artist of enough quality to have his own personality. It was an attributable picture, to use the term that art historians use.”

Marciari returned the rack to its slot and went on with other things. But he was intrigued. He learned that it had sat for many years, largely overlooked, in the basement of Yale’s Swartwout building—a “perfectly respectable museum storeroom,” he says. “It’s not as though Yale was keeping this in the steam cellar.”

Marciari found himself returning to the storage facility every week or two to study the canvas. Then, a few months after the first viewing, he pulled it out and studied it some more. “And the penny dropped, the light bulb went on, the angels started singing,” he says. “The whole moment of epiphany where you say, wait a minute—wait, wait, wait. I know exactly what this is. This looks like early Velázquez!”

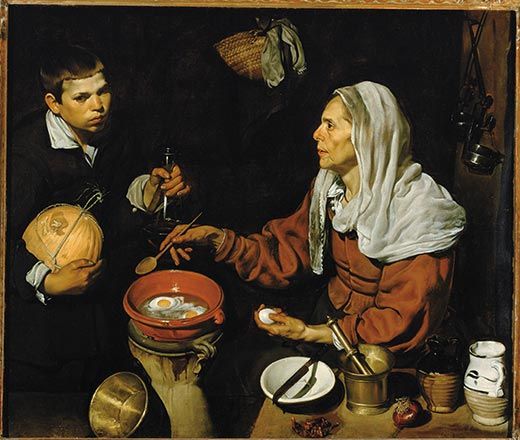

A flood of associations involving the 17th-century Spanish master Diego Velázquez came to mind—images Marciari knew from his academic work, museum pilgrimages and classes he had taught in early Baroque art. “This is the drapery from the Saint Thomas in Orléans,” he realized, with gathering excitement. “It’s like the Old Woman Cooking Eggs at Edinburgh, the Kitchen Scene in Chicago and Martha and Mary in London. All of it was familiar—the color palette, the way the figures emerged from the darkness, the particulars of the still-life elements, the way the draperies folded.” But it just couldn’t be, he thought. “I must be insane. There’s no way I just found a Velázquez in a storeroom.”

His caution was well founded. It’s one thing to form an intelligent hunch and quite another to satisfy Velázquez scholars and the international art community. This wasn’t a ceramic pot on “Antiques Roadshow.” It was potentially a landmark work by a towering figure who had changed the course of Western art and whose paintings are treasured by the world’s leading museums. Velázquez’s known works number in the low hundreds at most; their identification has led to controversy in the past. (In recent months, New York City’s Metropolitan Museum of Art generated headlines when it reattributed a portrait of Spain’s King Philip IV to Velázquez after having demoted it, in effect, 38 years earlier.) Nonetheless, Marciari had formed his hypothesis and resolved to plunge ahead. “Despite my initial doubts and the seeming impossibility, I think I felt pretty sure,” he says, “although with a great deal of anxiety.”

The first person he consulted was his wife, Julia Marciari-Alexander, an art historian specializing in British art.

“I put a picture in front of her and said, ‘What do you think of this?’ She doesn’t like playing that game. But she had just been in Edinburgh about a month before and had spent a great deal of time standing in front of Old Woman Cooking Eggs. And so she looked at it, and she said, ‘You know, that looks just like the Velázquez in Edinburgh.’”

Over the months, Marciari immersed himself in scholarship about Velázquez’s native Seville in the early 17th century, and he quietly brought the canvas to the university’s conservation laboratory for X-ray analysis. The lab confirmed that the pigments, priming layer and canvas were consistent with other early works by Velázquez.

By the spring of 2005, Marciari was sufficiently emboldened to approach his colleague Salvador Salort-Pons, a Velázquez expert who is now the associate curator of European art at the Detroit Institute of Art. “I wrote him an e-mail and said, ‘Salvador, I have what I think is a really important picture, but I don’t want to prejudice your opinion any more than that. Let me know what you think,’” Marciari says. He attached a digital photo.

Minutes later, he had a reply.

“I am trembling!!!!” it began. “That’s a very important painting. I need to see it. No doubt: Spanish, Sevillian....But I am afraid to say.” Salort-Pons traveled to New Haven twice to study the work, then pronounced his verdict: Velázquez.

Yet it was only after another five years of research, analysis and consultations that Marciari published his findings in the arts journal Ars in July 2010. Even then, he left the door open by writing that the painting “seems to be” the work of Velázquez. But he left no doubt about his own view, declaring the painting now titled The Education of the Virgin to be “the most significant addition to the artist’s work in a century or more.”

If Marciari welcomed the prospect of some healthy skepticism, he was unprepared for the coverage his journal article received across Europe, the United States and elsewhere. The story was picked up in newspapers from Argentina’s Clarín to Zimbabwe’s NewsDay, he notes. It was front-page news in El País, Spain’s leading daily newspaper.

“In America, I think much of the fascination with the story has to do with the discovery of treasures in the basement or the attic—the great payoff and all that,” says Marciari. He’s reluctant to guess what the canvas might fetch at auction. “It would be worth, even in its damaged state, an ungodly fortune,” he says. (In 2007, a Velázquez portrait was sold at auction at Sotheby’s in London for $17 million.) The Yale painting, Marciari believes, “is not a picture that will ever come up for sale.”

In Spain, where public attention was far more pronounced, the painting is invaluable in other terms. “Velázquez is a primary cultural figure in the history of Spain—he is the figure of Spain’s golden age,” Marciari says. “None of the kings was the kind of sympathetic character that Velázquez is. So every Spanish schoolchild grows up learning about the glories of the 17th century, and the illustration of that is always the paintings by Velázquez.” There is no comparable figure in American art, Marciari says. “It’s like finding Thomas Jefferson’s notes for the Declaration of Independence.”

Spanish experts have helped lead the way in endorsing Marciari’s attribution, among them Benito Navarrete, director of the Velázquez Center in Seville, and Matías Díaz Padrón, a former curator at the Prado. However, there are serious demurs, as well, notably that of Jonathan Brown of the Institute of Fine Arts at New York University, who is considered the foremost Velázquez scholar in the United States. After Marciari described his experiences with the painting in Yale Alumni Magazine last fall, Brown fired off a letter to the editor.

“For what it’s worth,” Brown wrote, “I studied the Yale ‘Velázquez’ in August, in the company of Art Gallery curator Laurence Kanter, and I concluded that it is an anonymous pastiche, one of many that were painted by followers and imitators in Seville in the 1620s. I published my views in ABC, a daily newspaper in Madrid, a few days later. Many veteran Velázquez specialists share this view. It’s a truism to say that time will tell, but we know that, in art as in life, not all opinions are equal.” Brown has not retreated from that view.

Laurence Kanter is Yale’s curator of European art. He said in January that he is “completely confident” in the attribution of the painting to Velázquez, but has since declined to comment. He understands, as Marciari does, that reasonable scholars will disagree. “You realize, of course, that in the field of art history there is almost never unanimity of opinion,” Kanter says. “And in the case of a major artist and a major shift in the accepted canon, it’s even more delicate. Frankly, I expected there to be even more controversy than there has been.”

Identified as a Velázquez, The Education of the Virgin was finally placed on exhibit in the Yale University Art Gallery in December 2010 for ten weeks.

Along with Oxford, Cambridge and Harvard, Yale has one of the world’s foremost university art collections, numbering some 185,000 works. Figuring out how the Velázquez came to be one of them required some detective work.

Marciari learned that the painting had been donated to Yale by two alumni, Henry and Raynham Townshend, the sons of one of the leading American merchant sailors of the 19th century, Capt. Charles Hervey Townshend. His ships frequently sailed to Spain, and it seems likely that the painting came back in one of them. In 1925, the brothers inherited the family’s New Haven property and began giving it something of a makeover. “This big, dark Spanish Catholic altarpiece must have seemed an odd thing shoved into the living room of a Gothic Revival mansion in Connecticut, ” Marciari says. “And obviously it wasn’t called a Velázquez.” He believes that the damage—including serious abrasion, paint loss and a portion cut off, leaving a headless angel at the top of the picture—were already present when the painting was donated.

Even before the canvas went on display, Colin Eisler, a former curator of prints and drawings at Yale, criticized the decision to publish images of The Education of the Virgin “in its present terrible condition,” as he wrote in a letter to the alumni magazine that appeared along with that of his NYU faculty colleague Jonathan Brown. “Why not have had it cleaned by a competent restorer first?”

Given the heightened public interest in the painting, Kanter says, Yale chose to show it just as it is. “There has been so much noise about the painting in the press that we felt that not to exhibit it would be tantamount to hiding it,” he says. “Our intentions here are to be as aboveboard as possible.”

That openness extends to the restoration of the painting, which clearly needs much more than a cleaning. There are many possible approaches to restoring a centuries-old work, and there is a real possibility of doing further harm. “It’s going to take us quite a long time,” Kanter says. “We’ve planned to spend much of this year simply discussing this painting with as many of our colleagues as we can bring here to New Haven to look at it with us. What we’re looking for is a means of treating the painting so that the damages that are now obtrusive are quieted, to the extent that you can appreciate what’s there as completely as possible.” Banco Santander, Spain’s largest bank, has agreed to sponsor the conservation and restoration efforts, as well as further evaluation of the painting by an expert panel and the eventual exhibition of the restored painting at Yale.

It will take all the expertise the university can muster to address the wear and tear this artwork has endured over nearly four centuries. Missing portions are not the worst of it, either. “Complete losses of paint are the easiest losses to deal with—holes in the canvas, or places where the paint is simply flaked away entirely—what you would call lacunae,” Kanter says, explaining that such sections are often surrounded by major clues about what was lost. Abrasion is more problematic. “And Velázquez had such a subtle and sophisticated technique, building up his colors and his modeling in layers,” he says. “So we cannot guess what’s gone, we cannot impose our own sense of what ought to be there—it’s simply not acceptable. And yet we have to find a solution where the first thing you see isn’t the damage.” Kanter adds, “No matter what we do is an intervention, but we’re trying to be as respectful and non-obtrusive as we can.”

Marciari left Yale in 2008 for his current position in San Diego, where he competes in ultramarathons when he is not tending to his 7-year-old twins (a girl and a boy). Although he is still aswim in the debates his discovery stirred up, he seems most animated when discussing the genius of the work.

Take the figure of the Virgin herself, staring straight out of the painting. “In breaking the picture plane, it almost seems as though you are meant to react or be part of the scene,” he says. “And I think that’s part of what Velázquez is doing, in the same way as he did 30 years later in his masterpiece Las Meninas [The Maids of Honor]. In The Education of the Virgin, the child is signaling to the viewer that they share a kind of secret—that she’s only pretending to learn how to read, because as the immaculately conceived Virgin Mary, born with full knowledge and foresight of the events of her and her son’s life, she knows how to read already. But she is pretending to learn as an act of humility to her parents.”

It’s a perfect example of the subtlety and insight—moral, intellectual and psychological—that Velázquez brought to his art. “As I looked into both the technical qualities of the painting and the depth of the artist’s interpretation of the subject,” Marciari says, “I saw the pictorial intelligence that sets Velázquez’s work apart from that of others.”

Jamie Katz reports frequently on culture and the arts.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jamie-Katz-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jamie-Katz-240.jpg)