A Worldwide Quest for Barbecue

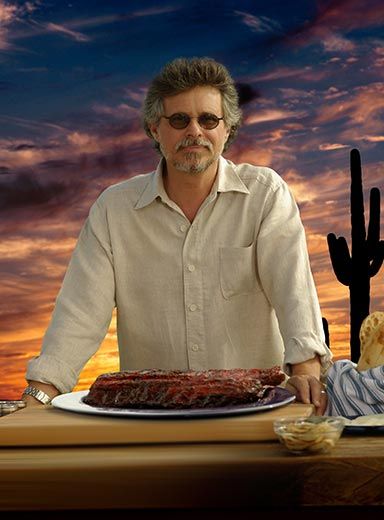

Steven Raichlen made a career teaching Americans all about barbecue, then an international tour taught him new ways to grill

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/barbecue-grill-631.jpg)

Steven Raichlen had no intention of heading to Colombia as part of his five-year odyssey exploring the world’s barbecue until hearing the rumblings about a strange dish, lomo al trapo, a beef tenderloin buried in a pound of salt and a few dried oregano flakes, wrapped in a cloth, and then laid on the embers to cook caveman style.

For Raichlen, who began writing about live-fire grilling 15 years ago, that’s all it took to get him on a plane to Bogotá.

By the evening of his first day in Colombia, Raichlen had been to six restaurants, each specializing in regional grilling, thanks to a local barbecue fan he met at a trade show, part of an extensive network of scouts and pen pals he has cultivated over the years. The lomo al trapo was, as expected, a succulent delight. Colombia, he found, grows beef in a cooler climate than the better-known South American barbecue favorites, Uruguay, Argentina, and Brazil. The result is an improved, richer flavor. “I’m sure there are about 8,000 Argentines who would lynch me for saying that, but it is,” he says.

Beyond the expected beef, he found other grilled delights, including arepas, corn meal cakes on the grill, grilled plantains and chiguiro (capybara), a sort of giant guinea pig roasted on sticks over a eucalyptus fire.

He also met Andres Jaramillo, owner of Andres Carne de Res, the rock star of Colombian cuisine. Jaramillo began his restaurant in Chia, outside Bogotá, as a six-table joint in 1982. Today, the restaurant is the largest in South America, a square city block that hosts 3,000 customers on a Saturday. It has its own art department of about two dozen that create tables, chairs and decorations for the dining room.

Colombia was typical of the discoveries on Raichlen’s quest. He set out expecting to find one thing—great beef barbecue—and was entranced by half a dozen others. “Colombia has some of the most amazing barbecue in South America,” he says. “I was amazed at the diversity of the grilling.”

Raichlen knew when he set off to research his latest book, “Planet Barbecue,” he was in for a long journey. He’d made a master list, but as the project progressed, he kept hearing about new places, places he couldn’t resist checking out: Azerbaijan, Cambodia, South Africa and Serbia, to name a few.

On the surface, Raichlen’s tour of 53 countries produced Planet Barbecue, a book of 309 recipes, profiles of grill masters both practical and eccentric, and tips for barbecue fans visiting each country. But he sees it as something more, as a book about culture and civilization. “As I’ve gotten into this field, I’ve come to realize that grilling very much has defined who we are as a people, as a species,” he says. “The act of cooking meat over fire, which was discovered about 1.8 million years ago, was really the catalyst, as much as walking upright or tool making, that turned us from ape-like creatures into man,” he says.

Raichlen’s passion for a smoky fire has produced more than two dozen books, including The Barbecue Bible, with four million copies in print. His television shows include Barbecue University, Primal Grill and Planet Barbecue. While he was classically trained at the Cordon Bleu, Raichlen is not a chef. He’s part recipe collector, part travel guide and part anthropologist.

In Cambodia, he and a guide set off on a motorized tricycle to the temple complex at Bayon in Siem Reap, far less known than the nearby temple at Angkor Wat. Along the way, he saw grills stalls along the road and they’d stop, taste and ask questions. There were chicken wings with lemongrass and fish sauce. There was coconut-grilled corn. And there were grilled eggs, made by mixing beaten eggs with fish sauce, sugar and pepper and then returning them to the shells and grilling them on bamboo skewers.

At the Bayon temple complex in Siem Reap, built to commemorate the victory of the Khmers over the Thais, Raichlen found scenes of life in military camps, including depictions of clay braziers resembling flower pots with blazing charcoal and the split wooden skewers used to grill lake fish.

Eventually, he did get to Angkor Wat. What intrigued him wasn’t the crowded temple, but the parking lot across the street hosting grills stalls to feed the bus drivers, tour guides and other locals. There, he had river fish skewered with a split stick cooked over a brazier, just like he’d seen in the Bayon temple depiction from 800 years ago. The next day he explored the central market in Siem Reap then took a cooking class with Khmer chefs teaching traditional dishes at a local resort. So it was 48 hours of live-fire cooking from the street to the linen tablecloth.

One of the things he likes about barbecue is that it can be both primitive and modern. Also it’s evolving. “It has one foot in the distant stone ages and one foot in the 21st century,” he says. And that technology means almost anything is possible with a fire, an understanding of those ancient methods and some imagination and ingenuity.

In France, he learned to cook mussels on a bed of pine needles ignited by the heat. In Baku, Azerbaijan, he met Mehman Huseynov, who dips balls of vanilla ice cream in beaten egg and shredded coconut and then browns them over a screaming hot fire. In Axpe, Spain, he came across a man he calls the mad scientist of barbecue, Victor Arguinzoniz, who makes lump charcoal from oak and fruitwood logs each morning to cook grilled bread with smoked butter or kokotxas a la brasa, grilled hake throats—a fish similar to cod and a Basque delicacy.

In Morocco, thanks to an American with a Moroccan restaurant he met in Atlanta, Raichlen was treated to a tour of Marrakech where he was introduced to Hassan Bin Brik, the “grandfather” of grilling, who founded the city’s first grill parlor in 1946 and makes kofta, a ground meat patty.

In each place, he found not only history and great food, but a look at who we are. Raichlen likes to paraphrase the 18th-century French gastronome and philosopher Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin. “Tell me what you grill and I’ll tell you who you are,” he says. “For me, it’s a window into a culture and a window into the human soul.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/jim-morrison-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/jim-morrison-240.jpg)