A Yuletide Gift of Kindness

Ted Gup learns the astonishing secret about his grandfather’s generosity during the Great Depression

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/The-Gift-B-Virdot-letters-631.jpg)

The year was 1933 and christmas was just a week away. Deep in the trough of the Great Depression, the people of Canton, Ohio, were down on their luck and hungry. Nearly half the town was out of work. Along the railroad tracks, children in patched coats scavenged for coal spilled from passing trains. The prison and orphanage swelled with the casualties of hard times.

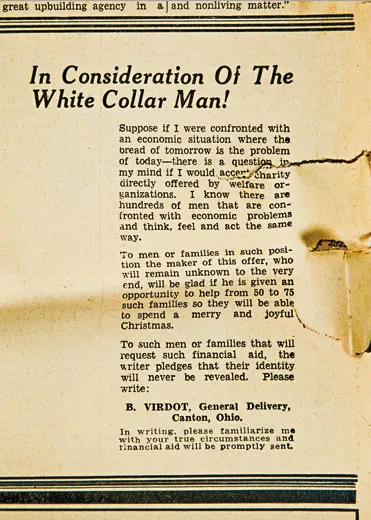

It was then that a mysterious "B. Virdot" took out a tiny ad in the Canton Repository, offering to help the needy before Christmas. All he asked was that they write to him and tell him of their hardships. B. Virdot, he said, was not his real name, and no one would ever know his true identity. He pledged that those who wrote to him would also remain anonymous.

Letters poured into the post office by the hundreds. From every corner of the beleaguered town they came—from the baker, the bellhop, the steeplejack, the millworker, the blacksmith, the janitor, the pipe fitter, the salesman, the fallen executive. All of them told their stories in the hope of receiving a hand. And in the days thereafter, $5 checks went out to 150 families across the town. Today, $5 doesn't sound like much, but back then it was more like $100. For many, it was more money than they had seen in months. So stunning was the offer that it was featured in a front-page story in the newspaper, and word of it spread a hundred miles.

For many of those who received a check signed by B. Virdot, the Christmas of 1933 would be among their most memorable. And despite endless speculation about his identity, B. Virdot remained unknown, as did the names of those he helped. Years passed. The forges and shops of Canton came back to life, and memories of the Great Depression gradually faded. B. Virdot went to his grave along with many of those he had helped. But his secret was intact. And so it seemed destined to remain.

Then in 2008—75 years later—and 600 miles away, in an attic in Kennebunk, Maine, my 80-year-old mother handed me a battered old suitcase. "Some old papers," she said. At first I didn't know what to make of them—so many handwritten letters, many difficult to read, and all dated December 1933 and addressed to a stranger named B. Virdot. The same name appeared on a stack of 150 canceled checks. It was only after I found the yellowed newspaper article that carried the story of the gift that I came to realize what my mother had given me.

B. Virdot was my grandfather.

His real name was Sam Stone. "B. Virdot" was a combination of his daughters' names—Barbara, Virginia (my mother) and Dorothy. My grandmother had mentioned something about his largesse to my mother when she was a young adult, but it had remained a family secret. Now, 30 years after her father's death, she was comfortable letting the secret out.

Collectively, the letters offer a wrenching vision of the Great Depression and of the struggle within the souls of individuals, many too proud to speak of their anguish even to their loved ones. Some sought B. Virdot's generosity not for themselves, but for their neighbors, friends or relatives. Stirred by their words, I set out to find what became of them, tracking down their descendants, wondering if the $5 gifts had made any difference. From each family, I received permission to use the letter. All of this I did against the backdrop of our own deepening recession, one more devastating than any since the Great Depression itself. I also set out to find why my grandfather made the gifts. I knew his early years had been marked by poverty—as a child he had rolled cigars, worked in a coal mine and washed soda bottles until the acidic cleansing agent ate at his fingertips. (Years later, as the owner of Stone's Clothes, a men's clothier, he finally achieved a measure of success.) But in the course of my research I discovered that his birth certificate was bogus. Instead of being born in Pittsburgh, as he had long claimed, he was a refugee from Romania who came to this land in his early teens and simply erased his past. Born an orthodox Jew and raised to keep kosher and speak Yiddish, he had chosen to make his gift on a gentile holiday, perhaps as a way of acknowledging his debt to a land that had accepted him.

Among those who wrote to B. Virdot was George Monnot, once one of Canton's most prosperous businessmen. Monnot had co-owned a Ford dealership that sometimes featured an 11-person band in tuxedos. His good fortune had also brought him a lakeside summer home, a yacht and membership in the country club. But by 1931, it was all gone. He and his family were living in an alley apartment among displaced workers, many of them unsure of their next meal. In his letter, he wrote:

For 26 years was in the Automobile business prosperous at one time and have done more than my share in giving at Christmas and at all times. Have a family of six and struggle is the word for me now for a living.

Xmas will not mean much to our family this year as my business, bank, real estate, Insurance policies are all swept away.

Our resources are nil at present perhaps my situation is no different than hundreds of others. However a man who knows what it is to be up and down can fully appreciate the spirit of one who has gone through the same ordeal.

You are to be congratulated for your benevolence and kind offer to those who have experienced this trouble and such as the writer is going through.

No doubt you will have a Happy Christmas as there is more real happiness in giving and making someone else happy than receiving. May I extend to you a very Happy Christmas.

Nine days later, Monnot wrote again:

My Dear Mr. B. Virdot,

Permit me to offer my sincere thanks for your kind remembrance for a Happy Christmas.

Indeed this came in very handy and was much appreciated by myself & family.

It was put to good use paying for 2 pairs of shoes for my girls and other little necessities. I hope some day I have the pleasure of knowing to whom we are indebted for this very generous gift.

At present I am not of employment and it is very hard going. However I hope to make some connection soon.

I again thank you on behalf of the family and an earnest wish is that you have a most Happy New Year.

But George Monnot would never again attain economic or social prominence. He spent his final days as a clerk in a factory and his evenings in the basement among his tools, hoping to invent something that might lift him up once more. His tool chest is now in the hands of one of his eight grandsons, Jeffrey Haas, a retired vice president of Procter & Gamble.

In some ways, Monnot was one of the lucky ones. He at least had a place to call home. Many of those who reached out to B. Virdot had been reduced to living as nomads. Worse, many parents gave up their children rather than see them starve. A woman named Ida Bailey wrote:

This Xmas is not going to be a Merry one for us, but we are trying to make the best we can of it. We want to do all we can to make the Children happy but can't do much. About 7 years ago Mr. Bailey lost his health and it has been nick & tuck ever since but we thank God he is able to work again. We all work whenever we can make a nickel honest. Three years ago this Depression hit us and we lost all our furniture and had to separate with our Children. We have 4 of them [out of 12] with us again. There are three girls working for their Cloaths & Board. I do wish I could have my children all with me once again. I work by the day any place I can get work...you know the wages they get don't go very far when there is 6 to buy eats for...I think if there were some more people in Canton like you and open up their Hearts and share up with us poor people that does their hard work for them for almost nothing (a dollar a day) when the time comes for them to leave this world I would think they would feel better satisfied for they can't take any of it with them....

One of the children the Baileys placed with another family was their son Denzell, who was 14 in 1933. His daughter, Deloris Keogh, told me he had moved more than two dozen times before he reached the sixth grade. He attended nearly every school in Canton at least once. He never had a chance to make friends, he said, or get settled or focus on his studies. He dropped out of the sixth grade and later worked as a bricklayer and janitor. But he vowed that his children would not endure the same rootlessness—that they would know but one home. So with his own hands he began to build a house of stone, gathering blocks from quarries, abandoned barns and a burned-down schoolhouse. Everyone knew of his determination, and friends and neighbors contributed stones to the house. A minister brought back a rock from the Holy Land. Others brought back stones from their vacations. Denzell Bailey found a place for each one. It took him 30 years to complete his house, a monument to his resolve. He died in it on November 23, 1997, at age 78, surrounded by his four children. It was the only home they had known. Denzell's house of stone remains in the Bailey family to this day.

When Edith May wrote to B. Virdot, she was living on a hardscrabble farm at the edge of town.

Maybe I shouldn't write to you not living right in Canton, but for some time I have been wanting to know somebody who could give me some help.

We have known better days. Four years ago we were getting 135 dollars a month for milk. Now Saturday we got 12.... Imagine 5 of us for a month. If I only had five dollars, I would think I am in heaven. I would buy a pair of shoes for my oldest boy in school. His toes are all out & no way to give him a pair.

He was just 6 in October. Then I have a little girl will be 4 two days before Xmas & a boy of 18 months.

I could give them all something for Xmas & I would be very happy. Up to now I haven't a thing for them. I made a dolly for each to look like Santa & that's as much as I could go. Won't you please help me to be happy?

Have you got any ladies in your family could give me some old clothes.

We all took a cold by not having anything warm to wear—it is the children's first cold & my first in ten years. So you can imagine our circumstances.

My husband is a good farmer but we have always rented & that keeps us poor. When we were making good money he bought his machinery & paid for them, so we never wasted anything. He is only 32 & never had anyone to give him a help in starting....

& oh my I know what it is to be hungry & cold. We suffered so last winter & this one is worst.

Please do help me! My husband don't know I am writing & I haven't even a stamp, but I am going to beg the mailman to post this for me.

No wonder Edith May complained of the cold: she was Jamaican. She had fallen in love with an African-American man with whom she had been a pen pal. They had gotten married and moved to a farm outside Canton. Edith May's "little girl" was named Felice. Today she well remembers her fourth birthday, two days before Christmas. When the chores were done, she and her family went into town. She remembers the Christmas lights. Her mother took her to a five-and-dime store and told her she could have either a doll or a wooden pony you pulled with a string. She chose the pony. It was the only present she remembers from those hard times, and only during our conversation last year did it occur to her that B. Virdot's check allowed her mother to buy such a gift. Today, Felice May Dunn lives in Carroll County, Ohio, and raises Welsh ponies—a love of hers since childhood.

Helen Palm was one of the youngest to appeal to B. Virdot. She wrote in pencil on a slip of paper.

When we went over at the neighbors to borrow the [news]paper I read your article. I am a girl of fourteen. I am writing this because I need clothing. And sometimes we run out of food.

My father does not want to ask for charity. But us children would like to have some clothing for Christmas. When he had a job us children used to have nice things.

I also have brothers and sisters.

If you should send me Ten Dollars I would buy clothing and buy the Christmas dinner and supper.

I thank you.

Finding Helen Palm's descendants was difficult. Her daughter, Janet Rogers, now 72, answered my questions about her mother—when she had been born, when she got married. Just as I was about to ask when her mother had died, Janet asked, "Would you like to speak with my mother?"

It took me a moment to collect myself. I had discovered the last living person to write to B. Virdot.

Even at age 91, Helen Palm, a housewife and great-grandmother, remembers the check she received in 1933. She used the money to buy clothes for her brothers and sisters, just as she had said she would do in her letter, and to take her parents to a nickel show and to buy food. But first, she bought herself a pair of shoes to replace those she had worn through and patched with a cardboard insert cut from a Shredded Wheat box. "I did wonder for a long time who this Mr. B. Virdot was," she told me. Now she is the only one among all those who sought help that Christmas 77 years ago to live long enough to learn his true identity.

"Well," she said to me, "God love him."

Ted Gup is the author of three books, including the new A Secret Gift, which documents his grandfather's largesse. Photojournalist Bradley E. Clift has worked in 45 states and 44 countries.