What Makes the Advice Column Uniquely American

In a new book, author Jessica Weisberg dives into the fascinating history of the advice industry

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3a/30/3a305157-18e2-495d-ac33-99ec2e3d1664/pauline-phillips-ann-landers_2.jpg)

When she was six years old, Jessica Weisberg went on a family trip to Washington, D.C. Somewhere between the tour of the Arlington Cemetery and a visit to the Thomas Jefferson Memorial, she had a dizzying revelation: all the sites they were walking through had been erected for people who had died. Then she realized that one day, she, too, would die. So would her family. So would everyone she’d ever met.

The next thing she knew, she was throwing up.

To soothe her existential angst, her parents arranged for her to start meeting regularly with a family friend who had the kind of personality that made her easy to talk to.

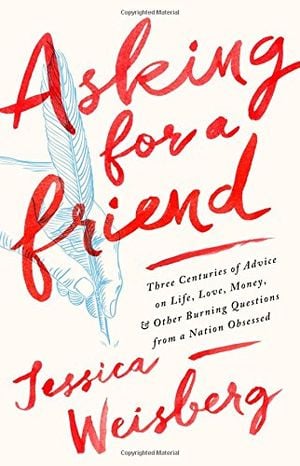

“It’s my first memory of being in a vulnerable position and needing someone to give me guidance,” says Weisberg, who recounts the incident in her new book Asking for a Friend: Three Centuries of Advice on Life, Love, Money, and Other Burning Questions from a Nation Obsessed, which chronicles the lives of 15 people who made their names doling out the answers to life’s many questions.

At some point, everyone seeks out advice. What is life, after all, but a series of inflection points with no instruction manual attached? One moment you’re soaking in the history of the nation’s capital and the next you find yourself clutching your stomach as you come to terms with your own mortality.

But whom do people turn to in search of answers?

“Of course people can go to people in their communities; they can go to their rabbi, their priest, their family, their teacher for advice,” says Weisberg. “I think what’s interesting is what makes people want to go outside that community.”

Asking for a Friend pulls back the curtain on the professional advice givers who’ve risen to national prominence—from the 1700s to the modern age—by fulfilling that need, yielding an incredible influence over societal norms in the process. “I didn’t feel anything had been written that addressed the power that they had,” says Weisberg.

Take Dr. Benjamin Spock, the American pediatrician whose advice on childrearing had presidents knocking down his door for an endorsement. Or how with just one column, the dueling sisters behind Dear Abby and Ask Ann Landers, Esther Pauline Friedman and Pauline Esther Friedman, could popularize the importance of creating a living will or work toward normalizing gay rights.

Ultimately, Weisberg says, she came to see the book as a story about who determines social norms, how they determine them and why people listen to them.

During the writing process, the election of President Donald Trump made her think especially hard about just how influential the self-help industry could be. “He is a president who gained a ton of interest by writing an advice book,” says Weisberg, referring to The Art of the Deal. “[With Trump], it’s not an issue of cultural or soft power but it's also real political power as well, so that really impacted me and made the stakes of the book seem higher.”

Weisberg traces the very first best-selling advice book back to the 18th century. The book, which hit the shelves in 1774, was written by Lord Chesterfield, a scheming social climber who never intended for his correspondences with his son Philip to be published. Nevertheless, when Philip’s widow needed a way to pay the bills, she compiled her father-in-law’s many lectures on how to act in polite society into Lord Chesterfield’s Letters.

The book became a cross-Atlantic hit despite— or more likely because—it proved such an infuriating read. (“Nothing,” Chesterfield once lectured his son, “is more engaging than a cheerful and easy conformity to other people’s manners, habits, and even weaknesses.”)

But even though its lessons were routinely mocked, American parents still turned to Chesterfield’s simpering responses. They did so, Weisberg argues, for the same reason they reached for Benjamin Franklin’s annual Poor Richard's Almanack—which delivered its own instructions on virtue and vice with characteristic Franklin wit during its run from 1732 to 1758—they wanted guidance.

Asking for a Friend: Three Centuries of Advice on Life, Love, Money, and Other Burning Questions from a Nation Obsessed

Jessica Weisberg takes readers on a tour of the advice-givers who have made their names, and sometimes their fortunes, by telling Americans what to do.

Weisberg makes the case that Americans in particular have a penchant for the advice industry. “It’s a very American idea that we can seek advice and then change our lot in life,” she says. It also reflects the mobility of American culture, showing Americans’ willingness to look outside of the values they were raised with. In turn, they allow for advice columnists to influence their ways of life, from how to properly sit at a table to the way they conceptualize divorce.

In the course of her research for the book, Weisberg says she was surprised to find that many advice columnists, who are often seen as the people responsible for perpetuating the status quo, were, in fact, using their platforms to promote social change.

For instance, Dorothy Dix, the pen name of Elizabeth Gilmer, used her Suffragette-infused prose to urge women to question their roles in society in her turn-of-the-20th-century column “Dorothy Dix Talks.” In one piece Weisberg highlights, Dix suggests a housewife go on strike until her husband learns to respect her. “Let him come home and find no dinner because the cook has struck for wages,” she writes. “Let him find beds unmade, the floors unswept. Let him find that he hasn’t a clean collar or a clean shirt.”

“Many of them were really trying to make the world a better place and a lot of them came from a position of great idealism,” says Weisberg.

The field of advice columns, as a whole, however, has a diversity problem, and it continues to leave many people of color out of the conversation entirely. “The platform has been given to white people over history, and that’s only starting to change now,” says Weisberg.

While she focuses on the national columnists—who skewed white, and only in the 20th century opened up to women writers—Asking for a Friend also notes the diverse selection of advice givers writing for specific communities throughout history, like the Jewish Daily Forward's "A Bintel Brief,” a Yiddish advice column that catered to new immigrants starting in 1906.

Today, the mainstream space still remains predominantely white, something that writer and editor Ashley C. Ford drew attention to in a 2015 tweet, which asked: "Who are some black, brown, and/or LGBTQ advice columnists?"

The tweet provoked a conversation on the lack of diversity represented in national advice columns, and also called attention to practicioners like Gustavo Arellano, now a weekly columnist for the Los Angeles Times, whose long-running satirical syndicated column “¡Ask a Mexican!” was adapted into a book and a theatrical production. The author Roxane Gay, who responded to the question by stating that there was a real absense of representation in the field, took a step to change that recently herself when she became an advice columnist for the New York Times.

Weisberg believes the proliferation of spaces to deliver advice in the digital age, in the form of podcasts, newsletters and such, as well as a change in editorial philosophy for publications that wouldn’t traditionally run advice columns, has also created an explosion in the form and an opportunity for new advice-givers to break into the conversation. Take Quora's Michael King for instance, who Weisberg explains made a name for himself by answering more than 11,000 questions on the community-fielded question-answer site.

One thing that Weisberg thinks won't change much about the form going forward are the fundamental questions being asked. Throughout her research, she says came across the same universal inquiries time and time again: How do you cope with the loss of a loved one? How can you tell if someone likes you? How can you know yourself?

“The questions overtime really underscored to me that the things that are challenging about being a person and having human relationships have always been challenging,” she says.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/eb/19/eb195034-f80c-4bd4-9dcc-02d2464e9203/dorothy_dix_1898_the_selfishness_of_men.jpg)

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.